Consider the ethical challenges of early retirement program offers

Regardless of why early retirement programs are being implemented by hospitals and health systems, considering ethical challenges before moving forward with any retirement program action can help healthcare financial leaders protect their organization’s reputation.

Hospitals and health systems implement retirement programs for a variety of reasons, such as meeting the goals of a merger or acquisition or cutting costs. Here are some recent examples of healthcare systems that implemented early-retirement programs:

- Advocate Aurora announced an early retirement buyout targeting 300 managers (Goldberg, S., “Advocate Aurora Health offers early retirement buyouts,” Crain’s Chicago Business, 2019).

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital announced a voluntary buyout targeting 1,600 employees who were 60 years old or older (LaPointe, J., “Hospitals turning to staff buyouts to reduce healthcare costs,” Recycle Intelligence, 2017).

Some organizations such as M.D. Anderson combine layoffs with voluntary retirement offers, where 1,000 jobs were eliminated in response to $100 million in losses in a single quarter (Ackerman, T., “MD Anderson cutting staff by 1,000 workers via layoff, retirement; no doctors affected,” Chron, 2017).

Planning ahead to deal with intended or unintended consequences

An example of an intended consequence would be drain brain, where some of the most skilled workers are removed from their roles. An example of an unintended consequences could be similar to what occurred with Osawatomie State Hospital, where an increased workload for remaining employees increased voluntary turnover (Wingerter, M., “Staff departures created ‘dangerous situation’ at Osawatomie State Hospital,” Kansas Health Institute [KHI] archives, 2016). Moreover, the same KHI archive article says, after federal inspectors investigated, a patient death was attributed to understaffing due to the early retirement.

Ethical challenges to consider

Just some of the ethical challenges that should be considered by healthcare leaders before moving forward with a retirement program offering are discussed in full below. These challenges include the following:

- Who are the direct and indirect stakeholders in any retirement decision?

- Are employees presented with the retirement program given all the information to make the best decisions?

- Do they have the capacity to make such decisions?

- Are the decisions purely financial?

- What are the possible design considerations for a retirement program and how will each impact targeted employees?

Stakeholder analysis

Different individuals and groups will frame an issue as ethical or unethical based upon a different understanding of the world and the nature of the relationship between individuals and organizations. To understand these different world views, a stakeholder analysis should be conducted.

The first step in the analysis is cataloging the stakeholders who are directly and indirectly impacted by the decision to accept or reject an early retirement buyout. The stakeholders include the following:

- The direct stakeholders are the employee and the agent of the organization who is typically a human resources representative.

- Indirect stakeholders are the family, friends and dependents of the employee as well as the co-workers of the employee and patients and family members of patients.

- The employees’ supervisors are also indirect stakeholders.

Although the decision to accept or reject the early retirement buyout is up to each individual, the impact may affect more than just the individual employee.

Motivations

Is the early retirement offer a purely a financial one? The decision to structure an early retirement offer has ripple effects beyond the eligible individual employee. For example, those who are not eligible may question whether the eligibility criteria are right or wrong. In addition, early retirement impacts the lives of others in the eligible employee’s household or someone who is under their care. As such, ethically sensitive healthcare financial leaders should ask three questions to challenge the notion that this is a financial decision alone because for many an early retirement is a major life decision.

- Who beyond the individual employee may be affected?

- Are the possible effects of the employee accepting the early retirement offer beneficial, neutral and/or harmful to the individual employee, other direct stakeholders and indirect stakeholders?

- What are the costs associated with these potentially beneficial, neutral and/or harmful effects?

Individual rights analysis

Another ethical challenge is considering whether the individual employee has the capacity or autonomy to make a fully informed decision and hence accept or reject the offer. The individual employee should be armed with the right information, right expert input and enough time to make a fully informed decision. The four questions to ask to help preserve the rights of employees as autonomous decision-makers are as follows:

- Does the individual employee have all the information in advance to make a fully informed decision?

- Does the individual employee understand the short- and long-term consequences of their decision given any possible information asymmetry between the individual employee and the employer?

- Do individual employees at all salary levels, educational levels and occupational groups have access to employer-sponsored or employer-covered retirement planning services to guide them in decision-making?

- Does the individual employee feel as if this early retirement buyout decision is separate and independent from any future layoffs, buyouts or reductions in force so as not to create a situation of coercion?

3 behavioral finance principles

The design of the early retirement offer and whether it is referred to as a buyout, early retirement, voluntary retirement or some other name is critical because of three behavioral finance principles.

- Framing tells the designer that what you decide to call the program matters in terms of impacting the decision and action. For example, if you use the word “offer,” then it suggests a greater sense of agency than “buyout.”

- If the “offer” is the default option and individual employees must communicate that they want to reject the offer, then you would have relied upon choice architecture — the design of ways choices can be presented — or a nudge. A nudge is a factor that influences behavior while maintaining choice. Some would assert that default options undermine agency and autonomy.

- If the early retirement offer is expressed as a multiple of base salary or some other type of formula, then the lump sum amount, particularly if taxes are not deducted, may unduly influence the individual employee to take the offer because of loss aversion. Loss aversion states that humans are hardwired to avoid losses and that a loss and gain of equal magnitude is not experienced the same way. Losses are more emotionally salient than gains of the same magnitude.

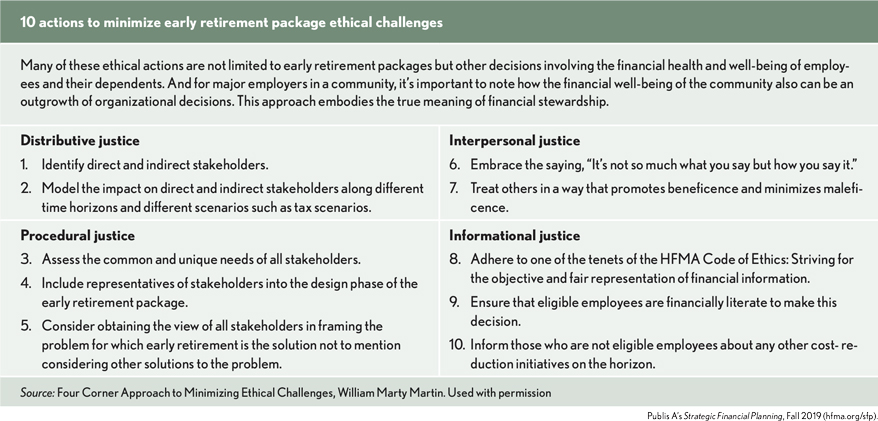

Cornerstones of organizational justice

There are four cornerstones of organizational justice: distributive, procedural, informational and interpersonal. Each one is briefly described below followed by its connection to early retirement offers.

Distributive justice. The focus for distributive justice is about the outcome of a process, decision or action. In the case of early retirement, the formula, the amount of money and the timing of the payout make up distributive justice. For example, is it perceived as fair to structure the buyout as 1.5 or 2 times the base salary? Should the buyout be grossed up for taxes or not?

Procedural justice. Procedural justice considers how the decision was made and by whom in deciding if an early retirement offer was even necessary or the right solution. Was it aligned to the right problem, or how the buyout was structured? Was the decision driven by a board committee? Was the decision isolated to finance, human resources and legal? Was the process delegated to an outside consulting firm?

Interpersonal. The focus of the interpersonal cornerstone is how the decision-makers, the communicators of the decision and the employees eligible for the early retirement offer are treated by those with more formal organizational authority over this decision/process. Are eligible employees hurriedly pressured to decide? Are the authorities in the process treating individual employees and the class of employees, which in this case is all eligible employees who meet a certain chronological age and years of service requirement, with dignity and respect?

Informational. The informational cornerstone stresses information ranging from the explanation as to why an early retirement package is the solution to the technical details of the package, ranging from tax consequences to retiree health benefits.

Distributive justice: A deeper dive

“Advocate Aurora initiates early retirement program for up to 300 managers” reads the June 12, 2019, headline of the lead story in the Milwaukee Business Journal. Contrast the headlines of early retirement offers and voluntary buyouts with lavish gains in executive compensation in the very same organizations in the same industry. Consider Alex Kacik’s June 22, 2019, Modern Healthcare article titled “Highest-paid not-for-profit health system executives earn 33% raise in 2017.” In at least one of the health systems mentioned in this article, the media profiled top pay for the health system executive while another media outlet profiled an early retirement buyout for employees. These two articles were published in the same month and year.

Imagine that there is a perceived inequitable pay discrepancy between the CEO and other members of the C-suite and the rank-and-file employees; then this situation within the walls of a healthcare organization should be regarded as a risk for the organization and perhaps a risk for the reputations of the CEO and members of the C-suite.

The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer shows that only 37% of respondents perceive CEOs as credible, which represents both a 17-year low and a decline by 12% from 2016 (Karlsson, P., Aguirre, D. and Rivera, K., “Are CEOs Less Ethical Than in the Past?” Strategy+Business, PwC, 2017).

Healthcare leaders would be wise to consider what is the perceived credibility of your organization? Is it advancing the strategic direction or serving as an obstacle, recognizing that there are multiple sources for credibility beyond compensation?

Distributive justice: Surgeons and physicians are taking note and keeping score

A relatively recent wrinkle in the pay disparity literature are comparisons between CEO pay and physician pay. The article, “The Growing Executive-Physician Wage Gap and Burden of Nonclinical Workers on the U.S. Healthcare System,” published in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 2018 highlighted two examples of pay disparity between 2005 and 2015:

- The wage gap between CEO compensation and orthopaedic surgeon compensation increased from 3:1 to 5:1.

- The wage gap between CEO compensation and pediatrician compensation increased from 7:1 to 12:1.

To be fair and balanced, CEOs and other members of the C-suite including CFOs, vice presidents of finance, comptrollers and treasurers have enormous responsibility to lead and manage increasingly complex healthcare organizations in increasingly turbulent environments. Yet, human perception of events is not always rational because as humans our emotions enter the equation.