The COVID-19-induced surge in healthcare labor costs is testing hospitals and health systems

Struggles with the pandemic’s financial impact on the workforce leave few alternatives besides innovation.

All good nurses have a passion for caregiving and healing, but they’re also human. And for some staff nurses, that makes the windfall being reaped by some of their new coworkers tough to stomach.

In response to a labor crunch that’s been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and health systems have substantially increased their use of contract nurses. That spike in demand inevitably has led to big raises for nurses who can travel to areas of high need.

Many of those nurses make double or triple the wages of the nurses on staff, causing a complicated dynamic for leaders striving to maintain a harmonious culture.

“Our teams are very committed, but it gets really challenging for them to work beside so many nurses that are making so much more than they are,” said Erica DeBoer, RN, chief nursing officer with Sanford Health, a multistate health system based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “It’s creating some of that unrest.”

And that’s just one aspect of the labor-cost issues that have stymied hospitals and health systems during the pandemic. Combined with nonlabor costs that have climbed dramatically amid disruptions to the supply chain, the increase in labor expenses is untenable, industry stakeholders say.

As a large health system with facilities primarily in rural markets, Sanford Health doesn’t have access to the same labor pools that are available to organizations based in major metropolises. But Luis Garcia, MD, president of Sanford Health’s clinic division, worries even more for facilities that are vital to their communities but lack the resources of a major system such as his.

“Think about the small hospital that has 20 beds and 20 nurses,” he said. “For them to lose three or four nurses is a huge impact. And for them to pay two, three, four, five times the salary of a nurse right now is unaffordable.”

That hospital may have to halt certain services as a result. If the hospital is in one of Sanford Health’s markets, the organization would have to cope with an influx of patients into a tertiary medical center that likely already has been operating at capacity in recent months. Access to care could be affected, and Sanford would be forced to spend even more on labor as it strived to meet the demand.

Such a scenario obviously has negative consequences for the rest of the budget. “All this is stifling innovation because the expenses that we have are putting boundaries on what is going to be our capital expense for next year,” Garcia said. “If we had a big piece of technology or a state-of-the-art service that we were going to invest in, right now we can’t.”

Numbers tell the story

Through September 2021, hospital employment had decreased by 93,000 since the start of the pandemic, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The reduction in September alone was 8,100.

The drop in supply has sparked a surge in wages as hospitals scramble to fill essential positions. Clinical labor costs have increased by an average of 8% per patient day compared with 2019, amounting to $17 million in additional annual expenses for a 500-bed hospital, according to data from PINC AI, a platform of Premier Inc.

“From a financial performance perspective, labor costs continue to be our biggest challenge,” said Nancy Hoffman, executive director of financial operations analytics with St. Louis-based Mercy health system. She said the organization’s contract labor expense has been nearly triple the historical rate in recent months, “and it continues to climb.”

A vexing aspect is that organizations are paying more for labor despite generally having less staff: In September, labor expense per adjusted discharge was 20.4% higher than in 2019, even with a 4.6% decrease in hospital staff per patient, according to Syntellis Performance Solutions.

Of course, that’s because hospitals have had to pay significantly higher wages to maintain operations. Overtime hours in September were 52% higher for hospitals and health systems compared with a pre-pandemic baseline, PINC AI reported in its analysis of data from 1,400 hospitals. Meanwhile, use of contract labor in FTE roles increased by 132%.

Correspondingly, the average weekly pay rate for contract nurses increased from $1,600 before the pandemic to $2,900 in early November, according to data from the recruiting company Vivian Health.

One factor underlying the bounces in overtime and contract labor utilization is a substantial rise in sick time. Especially when the delta variant caused the latest surge in cases, some clinicians and support staff simply could not keep going. Sick leave was up by 50% for full-time ICU clinical staff in September compared with pre-pandemic, PINC AI reported, while annual turnover among ED, ICU and nursing staffs has increased from 18% to 30%.

“The burnout, as you listen to hospitals, becomes more of the fabric of the story,” said Beth Cloyd, RN, DNP, MBA, principal, advisory service solutions with Premier.

The healthcare labor picture: By the numbers

534,000

Number of healthcare and social assistance workers who quit their jobs in August 2021 — the highest total going back to at least 2000, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

37,800-124,000

Range of the projected shortage of physicians by 2034, including up to 48,000 in primary care, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges

510,000

The pre-pandemic estimate of the nursing shortage in 2030, according to a 2017 study in the American Journal of Medical Quality

3.2 million

Projected shortage of support staff by 2026, according to Mercer, which examined “lower-wage healthcare occupations” such as medical assistants and home health aides

***

The following data are from NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc., “2021 NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report,” March 2021.

$40,000

Average cost of turnover for a bedside RN position, according to hospital survey responses

18.7%

The RN staff turnover rate in 2020, up from 15.9% in 2019

24.9%

The RN staff turnover rate in 2020 for hospitals in the Southeast, highest among five regions

13.2%

The RN staff turnover rate for hospitals in the Northeast, lowest among the five regions

Short-term fixes prove elusive

Bill rates for contract nurses are starting to come down, said Kelly Rakowski, group president and COO for strategic talent solutions with AMN Healthcare. Nevertheless, “We’re probably still several months out before those rates come back to pre-pandemic levels.”

Then again, making a viable prediction is difficult because of uncertainty surrounding both the future course of the pandemic and the extent to which healthcare labor shortages will prove to be structural.

“This market has been so volatile, and a little bit irrational,” Rakowski said.

“This market has been so volatile, and a little bit irrational,” says Kelly Rakowski, group president and COO for strategic solutions at AMN Healthcare.

That’s in part because hospitals now have to compete nationally for traveling clinical staff and for nonclinical staff who can work from home and thus have their pick of jobs across the country. Furthermore, the “Great Resignation” has opened the door to a mass shuffling of labor across industries. Federal, state and individual-organization vaccine mandates are another wild card.

And although much of the focus during the pandemic has been on nurses, administrative and support roles have been affected as well.

“Think about a registrar who was maybe making $10 or $12 an hour,” Garcia said. “Now you can be an Uber driver and make more money doing that, and you’ll have flexibility in your schedule. Or you can go to an industry that’s not as demanding, stressful and emotionally consuming as healthcare and make the same or more money.”

That reality makes it all the more meaningful when employees choose to stay in healthcare because they see it as a calling, he added.

Even as the delta surge began to ebb in October, Mercy was still seeing high inpatient census numbers driving contract-staff usage, premiums and incentives, Hoffman said. Plans are in place to reduce usage in coming months, she added, but careful execution is required because of lingering staffing gaps in many areas, including nursing, radiation therapy, environmental services, nutrition services and clinical support.

Rakowski touted the use of analytics to optimize float pools and pinpoint where clinical staff will be needed in upcoming months. She said an overlooked benefit is the potential of analytics to identify “leakage,” meaning instances of inefficiency that accumulate when staff work less hours than their full allotment. A sophisticated analytics program also can predict which staff are likely to depart the organization and when, allowing for recruitment to start before vacancies arise.

One of the most important things a provider can do in the near term is mitigate burnout by supporting its workforce. For example, Sanford Health is proactively bringing employee-assistance resources to individual clinics and hospitals “to help them really debrief from their days and transition to home and life outside their jobs more effectively,” DeBoer said.

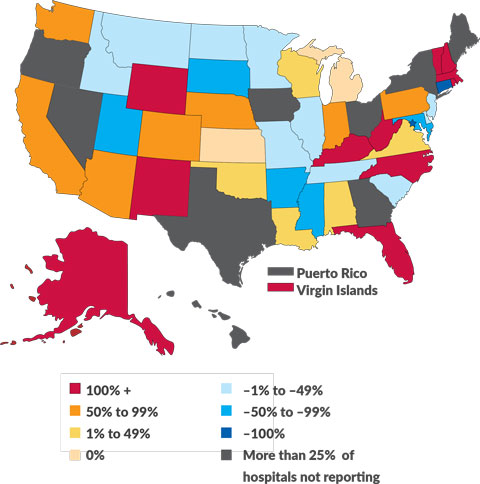

Critical staffing shortages

Percentage change in hospitals reporting a critical staffing shortage between Oct. 1, 2020, and Nov. 1, 2021

(Source: HealthData.gov: COVID-19 Reported Patient Impact and Hospital Capacity by State Timeseries)

Redeploying resources

“Even with the best of all these strategies, we’re not going to have enough staff,” Rakowski said. “We’ve got to look at the care model itself and [ask] how we create less dependence on labor and really augment [staff] with technology so that we can have more scale and create more access to services.”

That likely means automating high-volume transactional services, she added. “How can you reduce that dependence on humans and make sure that we’re using them in the most cost-effective way?”

That question will outlast the pandemic. Even if the financial crunch and operational challenges are alleviated to some degree in upcoming months, hospitals and health systems know they’ll have to stay flexible and keep innovating to make optimal use of their workforce.

As DeBoer said, “It’s really up to us to help redefine and adapt our workflows to meet the needs of our patients.”

Big-picture solutions worth considering

Some of the most significant responses to labor trends aren’t necessarily designed to get hospitals and health systems through the next fiscal year. But the following initiatives can help ensure the same kind of workforce crunch isn’t felt during the next public health emergency.

Payroll flexibility. In many organizations, a cultural shift is underway in how finance leaders evaluate operations.

“Back in the day, it was all about productive hours per equivalent patient day on the inpatient side,” said Nancy Hoffman, director of financial operations analytics with Mercy health system. “And that’s not a metric we’re extremely focused on anymore because that just led to cost escalation and constrained our most expensive resources. Now we’re really looking at skill-mix models.”

Mercy would sign off on hiring two FTEs in support roles to fill what previously was a single, higher-level payroll slot “if that’s a better care model in the long run, and more cost-effective,” Hoffman said — regardless of the impact on productivity measures.

A robust pipeline. Sanford Health is working to expand partnerships with colleges to serve as a conduit for new hires. A year-long residency program helps put new nurses on a track to “become that high contributor and that professional leader at the bedside,” said Erica DeBoer, RN, chief nursing officer.

Mercy has worked to enhance its pro re nata structures and regional float pools. It also is collaborating with a vendor to establish an app-based gig employment platform that will serve as “the next generation of travel nursing,” Hoffman said.

“We’re very optimistic that’s going to open up some new kinds of labor sources and provide opportunities for more local resources to pick up shifts, provide some of that flexibility and fill some of those gaps,” she said.

Right-sized care delivery. Well before the pandemic, efforts to cut down on higher-intensity care were underway in response to the increasing prevalence of payment models that give providers an incentive to keep patients out of the hospital.

“We don’t foresee external factors in the labor market changing anytime soon, so we are very focused on what we can do differently,” Hoffman said. The endeavor includes utilizing the virtual care center that the health system opened in 2015 and looking at ways to expand telehealth and health management programs.

“Anytime we can serve our patients and avoid an acute care stay entirely or provide specialist care to our patients in a rural hospital setting in their community, that’s a win for everyone,” she said.