Home Is Where the Hospital Is

An innovative payment model may bring home hospitalizations into the mainstream of “inpatient” care delivery, pulling more volume out of traditional acute care facilities.

The provision of inpatient-level acute care for low-acuity medical conditions in patients’ homes is not a new practice. But current Medicare payment restrictions have prevented this care delivery model from seeing widespread use. Those health systems that have deployed the hospital-at-home model, however, report higher-quality outcomes achieved at a lower cost compared with outcomes for patients with similar conditions admitted to acute care facilities. Recently, a proposal for a 30-day bundled payment model for the “hospital-at-home” approach to care was recommended by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) for further development and deployment. a If the CMMI elects to deploy the model, the implications for hospitals are significant, given the volume of admissions involved. Hospitals therefore should understand who might be interested in the model and what the financial impact of various participation alternatives will be.

How Home Hospitalization Works

Hospital-at-home models are being piloted in a limited number of health systems across the United States. Typically, these are health systems that have a health plan; examples include Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Presbyterian Healthcare Services (PHS) in Albuquerque, N.M., and Marshfield Clinic Health System in Marshfield, Wis. However, a 2011 Commonwealth Fund report points to the successful deployment of the model in other countries for many years. b

A patient can be referred to the program from a community physician practice or an urgent care center, or by a hospital emergency department (ED) physician. In Marshfield Clinic Health System’s model, 70 percent of hospital-at-home admission referrals occur in the ED. A care coordinator performs triage on patients to determine which ones are appropriate for the model, and a hospitalist confirms the likelihood that each identified patient will fall into one of the appropriate MS-DRG categories. Narrowly defined eligibility criteria help identify patients who require intensive services and/or multiple visits from a specialist and, therefore, should be treated in an acute setting. Further, many models use either Milliman or InterQual guidelines to verify that the patient meets appropriate criteria for a hospital admission.

The patient evaluation can occur in person—most often in an ED—or by telephone from a community setting. As the suitability of the patient’s home is evaluated and necessary durable medical equipment is delivered to the home, required medical care begins (e.g., intravenous administration of antibiotics) and responsibility for care is assigned to a physician.

A caregiver meets the patient at home, and a physician—either in person or through an online communication medium—explains the treatment protocol. Orders are written, and clinical staff—including respiratory therapists, physical therapists, and other caregivers—arrive as needed to administer intravenous medications and fluids, provide nebulizer treatments, and perform examinations, including ultrasounds, X-rays, and electrocardiograms. Meals are arranged, if necessary. The patient’s vital signs are monitored electronically.

The physician visits the patient daily either in person or, more likely, via a telemedicine platform. To capture any decline in the patient’s condition when clinicians are off site, providers use remote patient-monitoring technology.

Once a patient is stabilized and well enough to return to activities of daily living, the patient is handed off to his or her primary care physician. In some models, participating providers maintain oversight of the patient for at least 30 days, to ensure the patient is keeping appointments and is not suffering any adverse consequences. During this period, the physician provides updates to the patient’s primary care physician.

Impact on Cost and Quality

A home hospitalization model has the potential to reduce the total cost of care while improving outcomes. Early pilots have achieved savings of 30 percent per admission. The lion’s share of savings has been attributed to factors such as lower costs for diagnostic testing and pharmacy, less clinical service consumption, cost avoidance due to prevention of complications, and flexibility in the staffing model. c

These savings have been achieved with fewer complications and greater patient satisfaction, according to the previously cited Commonwealth Fund report. For example, early trials have found incidence of delirium was approximately 63 percent lower for patients admitted to the hospital-at-home model. An HFMA member whose organization is currently using this model with members of its Medicare Advantage plan reports patient satisfaction is 27 percent higher than clinically comparable patients who were hospitalized.

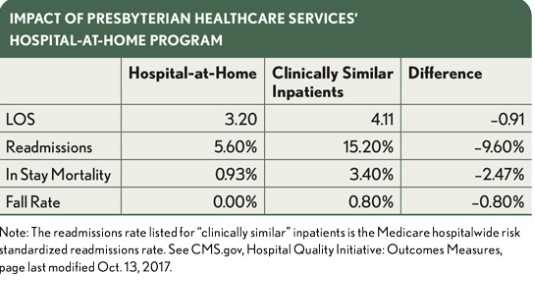

The exhibit at left compares PHS’s hospital-at-home program’s outcomes with those experienced by clinically similar patients hospitalized in an inpatient setting.

Although patient selection may explain some of the difference in readmissions rates, a hospital-at-home model has advantages over an acute care admission that help realize lower return rates. Having caregivers in the patient’s home (either in person or virtually) for 30 days post-discharge provides a better opportunity to perform a range of activities such as assessing fall risks, screening for and addressing social determinants of health (e.g., food insecurity or mal-diet), reconciling medications, and providing detailed patient education. Nonetheless, despite the ability of home hospitalizations to produce superior patient outcomes at a reduced cost, they have seen minimal use for want of a viable financing model.

Details of the Payment Model Proposed to the PTAC

The 30-day episode of care for a home hospitalization was presented to the PTAC at its meeting on March 26, 2018. Under the proposal, an episode would begin three days prior to admission and end 30 days post-discharge from the hospital at home service. A risk-adjusted target price, based on the regional average, would be developed based on each MS-DRG included in the program. The prospectively set target price would include the following:

- The MS-DRG payment for services provided during the “initial hospitalization” reduced by 30 percent to reflect a lower-cost setting

- Physician services provided during the home hospitalization

- Physician services related to the admitting diagnosis furnished in the 30-day post-discharge period

- Other outpatient services (e.g., ED visits, diagnostic imaging) related to the admitting diagnosis incurred in the 30-day post-discharge period

- Post-acute care (PAC) services provided during the 30-day post-discharge period related to the initial home hospitalization

- Subsequent hospitalizations (e.g., readmissions) related to the admitting diagnosis incurred in the 30-day post-discharge period

The model offers CMMI a 3 percent discount on the full target price. Although quality measures are not currently used to adjust the benchmark, the model includes a robust measure set that could be incorporated into the payment model. The proposed measures include scores on Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS); rates of hospital-acquired conditions; and condition-specific outcomes with respect to mortality, readmission, ED utilization, and patient-reported experience. Because quality measures are integral to the model, if CMMI develops a model, it is likely a track that qualifies for the advanced alternative payment model (APM) bonus under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) will be offered.

The hospital-at-home model was proposed as a “retrospective model.” If accepted, CMS will continue to make fee-for-service payments to any provider who delivers a service related to the episode of care. Results will be determined using a retrospective reconciliation process similar to that used with the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) and Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) models. As it is currently presented, the model caps maximum gains at 10 percent.

Applicable Conditions

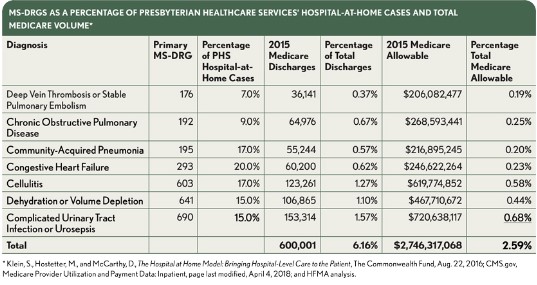

The hospital-at-home model typically is used for a limited number of medical MS-DRGs. As an example, the exhibit below lists the MS-DRGs included in PHS’s hospital-at-home model. To give a sense of the potential volume impact, the chart also includes the total number of Medicare admissions, the Medicare “allowable,” and the percentages of each MS-DRG relative to the national total Medicare volume.

If it is adopted, a Medicare hospital-at-home payment model could have a significant impact on hospitals in markets where it is deployed. The limited number of conditions targeted by PHS’s program likely include many of the conditions that would be covered by a CMMI pilot. These conditions account for approximately 6 percent of Medicare discharges and 2.5 percent of total Medicare inpatient payments. Although these MS-DRGs are typically unprofitable, their contribution margins cover the fixed and step-fixed costs inherent in running a hospital. Further, the number of MS-DRGs covered would likely expand quickly with CMMI’s and providers’ growing experience with home hospitalizations.

Although the seven MS-DRGs listed in the exhibit represent the majority of hospital-at-home admissions, the proposal presented to the PTAC includes about 150 MS-DRGs. This breadth is supported by HFMA’s conversations with senior finance executives whose organizations are experimenting with home hospitalizations. These executives believe the model will support an expansion in the number of surgeries that can be performed on an outpatient basis. Common examples cited include low-complexity hip and knee replacements for Medicare beneficiaries. Given the potential for volume disruption, hospitals and health systems need to understand what types of entities might vie for this market share.

Increased Competition for ‘Inpatient’ Services

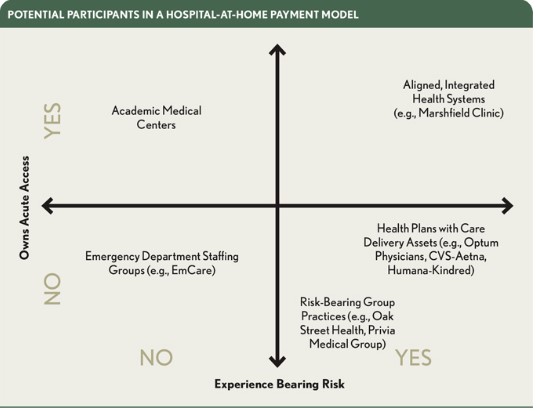

A 30-day Medicare home hospitalization episode payment model would attract a mix of incumbents and new entrants into the market for low-acuity inpatient services. The relatively low capital requirements would encourage physician groups (or entities that employ physicians) that are involved in the decisions to refer patients for admission to participate on an experimental basis. Beyond a new revenue stream, such a model would buttress existing population health management strategies. The exhibit below illustrates the types of organizations (both existing competitors and new entrants) that might participate in a pilot.

As discussed below, each of the potential participants and brings specific advantages to a hospital-at-home model and has a different rationale for joining a CMMI pilot.

Academic medical centers (AMCs). Many AMCs have reached or are close to exceeding inpatient capacity. They may look to a hospital-at-home model as a way to serve more patients without having to invest a million or more dollars per bed to create additional capacity. Moreover, the model provides a way to divert lower-acuity admissions to sites where care could be provided at reduced per unit labor costs. Joint venturing with primary care physicians in adjacent markets also may create an opportunity to leverage an AMC’s traditionally strong brand and gain market share at the expense of other hospitals.

Aligned, integrated health systems. Aligned, integrated health systems typically employ many of the physicians that provide care in the system and own a health plan. Almost all of them also are involved in some form of Medicare fee-for-service accountable care organization (ACO). For these health systems, deploying the hospital-at-home model within their own health plans and to the Medicare fee-for-service population provides a means for supporting their population health management strategies and leveraging existing care coordination capabilities.

ED staffing groups. ED physicians triage and write admission orders for many patients who have low-acuity medical conditions that could be treated in a hospital-at-home model. Participating in a hospital-at-home model could create a new revenue stream for ED staffing companies. Further, assuming the model has a qualifying track, episodic payments for home hospitalizations could provide an avenue for ED physicians to receive the advanced APM incentive payment available under MACRA. Most ED staffing groups lack the capabilities to deliver home-based care. However, a joint venture between one of the national ED staffing companies, a national home care provider, and one of the companies that provide the necessary technology platform isn’t hard to imagine. d

Risk-bearing group practices. Given their relationship with and proximity to Medicare fee-for-service patients with multiple chronic conditions, a number primary care group practice models stand to gain financially from a hospital-at-home model. One example is Oak Street Health in Chicago. Oak Street Health focuses on delivering care to historically underserved populations. Although its business model is predicated on sub-capitated payments for primary care from Medicare Advantage plans, the organization does deliver care to Medicare fee-for-service patients. Such group practices have the analytic capability, experience with virtual monitoring and care delivery, and patient navigation skills to successfully execute the model. Beyond creating an additional revenue stream for the practice, adopting the model could enable these practices to develop relationships with patients that serve as stepping stones to migrating them into an aligned Medicare Advantage plan.

Health plans with care delivery assets. Recently, the market has experienced a wave of mergers in which health plans have acquired providers or increased their direct healthcare delivery capabilities. Such efforts are likely focused in part on decreasing utilization and costs for the health plans’ members and increasing the plans’ market share. However, this strategy also provides health plans with a platform to generate incremental revenue by managing Medicare fee-for-service lives. With its acquisition of DaVita Medical Group (DMG), Eden Prairie, Minn.-based Optum now has approximately 37,000 employed physicians. e The transaction is a prime example of a health plan expanding its reach into the Medicare fee-for-service, because DMG practices participate in Medicare ACOs in a number of markets. In the 30 markets where Optum has physician practices, the practices’ existing relationships with Medicare patients coupled with their analytic and care coordinating capabilities make them a natural entrant.

For acute care providers, participating in a hospital-at-home model likely will decrease revenue related to the impacted MS-DRGs. However, the question management teams need to answer is whether there’s greater financial risk in cannibalizing this revenue stream or ceding the volume to other, well positioned competitors.

Understand your exposure. How much of a hospital’s margin is attributable to admissions that could be managed at home? If a hospital elects to develop its own hospital-at-home model, what net-net impact would this strategy have on the cost of care delivery. A review of the list of MS-DRGs in the exhibit on page 47 and the proposal to the PTAC are good places to start. However, finance staff should work with medical staff to understand the full universe of low-acuity, high-volume admissions where care could be effectively delivered in the patient’s residence with home and telehealth visits. They also should seek to understand the sources of admission for these cases and identify which physicians (or physician groups) are responsible for referrals.

Understand your opportunity. Two key questions should be addressed in assessing the opportunity: For the MS-DRGs that will likely be targeted, what will the target price be? And is there excess clinical utilization or testing that can be reduced? Reviewing a hospital’s Medicare data on spending per beneficiary for each MS-DRG can provide clues as to potential opportunities to offset lower MS-DRG revenue through downstream savings.

Understand your market. To understand the types of entities a hospital will compete with for home-based admissions, it is necessary to assess, first, which physician practices are responsible for referrals for the conditions that can be managed at home and, second, which entities in the market are capable of organizing and managing care delivery at home. Organizations that meet both criteria are the most likely entrants, but it’s unclear how many entities can check both boxes. Therefore, any entity satisfying one of the criteria should be viewed as a potential competitor (or partner). It’s probably best to err on the side of caution instead of prematurely discounting a potential entrant. As noted above, there are firms that can help potential entrants fill capability gaps to enable the entrants to successfully execute a hospital-at-home model.

Understand your capabilities. Among other questions, acute care organizations that execute a hospital-at-home model will need to answer the following.

First, how will the suitability of a patient and the patient’s home for the model be determined? This can be an especially challenging undertaking given the potential multiple referral points (e.g., ED, physician office, urgent care clinic) and may imply a centralized call center solution for patient assessment.

Second, once a patient is deemed suitable for the model, how will the necessary medical equipment be promptly delivered to the home? Beyond considering geographic boundaries, a hospital may need to develop deeper relationships with a durable medical equipment (DME) provider in the market(s) where they offer a hospital-at-home model.

Third, how will care be delivered once the patient is “admitted” to his or her home? The mix of services delivered will depend on the condition-specific care protocol and the severity of the patient’s condition. To address this consideration, hospitals may need to develop a “hospitalist at home” program, deepen existing relationships with home health agencies, or beef up their telehealth and monitoring capabilities.

Fourth, once the patient is “discharged,” how will the provider monitor and support the patient during the 30-day post-discharge window? Providers will need to develop a mechanism to track patients after discharge to ensure the patients are adhering to their care plans. Further, given the role of social determinants of health in readmissions, hospitals will need to develop deeper relationships with social service providers to address nonmedical needs and reduce readmissions.

Develop a response plan. A hospital’s response will depend on its perceived exposure to the model and other pressing priorities. Actions could range from monitoring events in the market and payment environment to executing a limited pilot program focused on one condition even before a clear payment model emerges. Using a limited pilot will allow a hospital to develop essential relationships and gain experience before bringing the delivery model to scale.

Footnotes

a. See Murali, N.S., “ Home Hospitalization: An Alternative Payment Model for Delivering Acute Care in the Home: A Proposal to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee,” Personalized Recovery Care, LLC, Oct. 27, 2017; and Miller, H.D., Meadows, R., and Nichols, L.M., Preliminary Review Team Report to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) on the PRC Home Hospitalization Alternative Payment Model, PTAC, Feb. 23, 2018.

b. Klein, S., “ Hospital-at-Home” Programs Improve Outcomes, Lower Costs but Face Resistance from Providers and Payers,” The Commonwealth Fund, Quality Matters, August-September 2011.

c. Foubister, V., “ Hospital at Home Program in New Mexico Improves Care Quality and Patient Satisfaction While Reducing Costs,” The Commonwealth Fund, Case Study, August-September, 2011.

d. Castellucci, M., “ Innovations: Bringing Hospital-Level Care Home,” Modern Healthcare, Aug. 6, 2016. \

e. Haefner, M., “ With 8k More Physicians Than Kaiser, Optum Is ‘Scaring the Crap Out of Hospitals,’“ Becker’s Hospital Review, April 9, 2018.

The author gratefully acknowledges Gordon Edwards, CFO, Marshfield Clinic Health System, for his contributions to the development of this article.