How a West Texas hospital used a PSH to improve outcomes and cut costs

Jasper Mesarch, DO, MBA, FASA

Jeffrey N. Rubin, DO

Adam H. Adler, MD

Elizabeth Snyder, MBA

Marc E. Koch, MD, MBA, FASA

Geriatric hip fractures are a major cost driver for the nation’s healthcare system in general and for hospitals in particular.

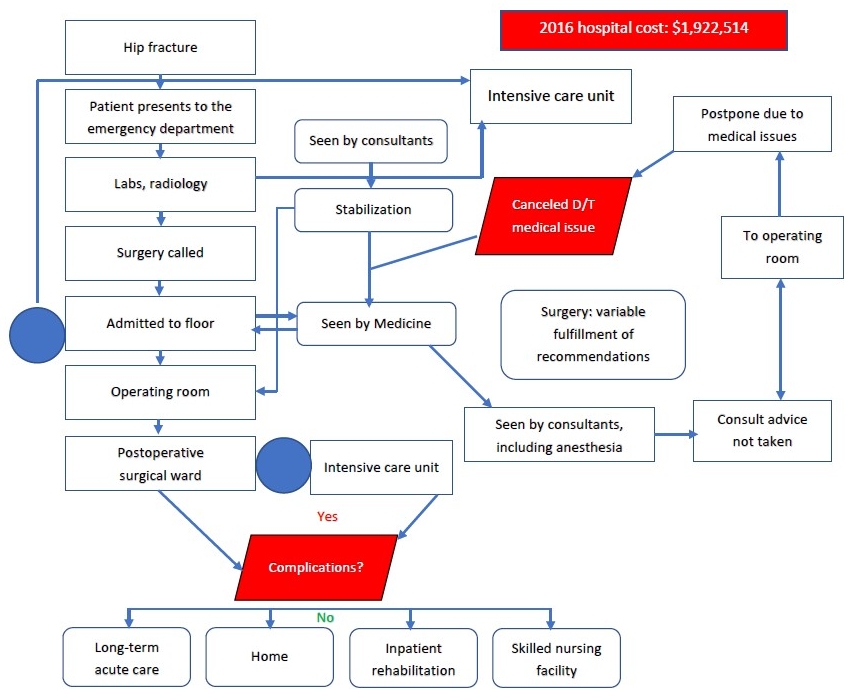

The burdens hospitals experience from such events are exacerbated by frequent delays from the time patients present to the emergency department (ED) to the time they receive surgery and by potential postoperative complications. These delays, involving middle-aged to geriatric patients, may be a consequence of more frequent (or more comprehensive) evaluations of the diseases of aging, such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. To address this challenge, hospitals should revisit care processes to identify inefficiencies and opportunities for process improvement.

Marshalling the precepts of an emerging area of specialized medicine, perioperative medicine, the perioperative surgical home (PSH) is a possible answer to this challenge. Hospitals and health systems are increasingly adopting this approach to enhance outcome measures in various surgical populations that have been shown to benefit from it, including geriatric patients who have suffered hip fractures. University Medical Center (UMC) of El Paso, in El Paso, Texas, is a case example. UMC’s experience with establishing a PSH provides insight into the potential benefits of such an evidence-based approach for improving care for geriatric hip fractures and into the strategy and tactics required to re-engineer perioperative processes. (see the sidebar, “Defining characteristics of PSHs,” below.)

UMC launched the PSH as a pilot program called the El Paso Hospital Hip Fracture Pilot. It resulted in improved patient access and clinical outcomes while reducing perioperative costs for the hospital. Here we discuss the planning and implementation stages from the initiative as well as key results and takeaways.

UMC’s 2015 baseline

UMC is both an American College of Surgeons (ACS) Level 1 Trauma Center and a safety-net hospital that delivers care to a high percentage of vulnerable Medicaid and uninsured people on the U.S.-Mexico border in West Texas. Before the pilot, the hospital suffered bottlenecks related to imperfect care coordination among the emergency and admitting departments, surgeons, primary care clinicians and anesthesia personnel, and to operating room (OR) availability. At baseline in 2015, prior to the pilot, the average time a patient with a hip fracture waited to have surgery was 47 hours, compared with the average International Geriatric Fracture Society (IGFS) goal of 36 hours. Patient flow was unstandardized, imperfectly coordinated, untimely and inefficient, leading to runaway increases in hospital costs.

Before: Flow chart of patient care for hip fracture prior to the pilot program

Source: University Medical Center of El Paso, 2020

PSH goals and objectives

Implementing precepts of evidence-based perioperative medicine, a team of academic orthopedic surgeons from Texas Tech University of Health Sciences, and private anesthesiologists/CRNAs collectively embarked on developing the PSH for a cohort of geriatric patients who had hip fractures. The effort was prompted by a PSH initiative advanced by the American Society of Anesthesiologists, a multidisciplinary collaborative involving a variety of organizations, including the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS).a UMC’s executive team quickly stepped in to support the initiative, given the opportunity to optimize perioperative outcomes, reduce complications and improve healthcare delivery to the community. Indeed, the UMC COO attended a national PSH meeting to ensure the organization understood and could strongly support the perioperative care model.

To meet the imperatives of the PSH regarding improved patient health outcomes, experiences, access, and to coordinate care delivery models with lower episode-of-care costs, UMC re-engineered the perioperative care process for pilot patients. Process re-engineering led to institutional changes, outlined in the discussion below, to achieve three objectives:

- Streamlined/standardized protocols based on evidence-based perioperative medicine tenets

- Enhanced patient care outcomes (clinical and experiential) and access

- Conserved resources

These three objectives, which are based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim principles, are organically interrelated. Results have shown that squeezing out inefficiency and waste and refocusing resources on targeted activities to optimize modifiable risk factors can improve patient outcomes, with fewer and less severe postoperative complications. Complications such as delirium, post-operative cognitive disfunction, acute renal disease, pulmonary disorders and surgical-site infections can be relatively inexpensive to preempt, but they are costly to treat. UMC recognized that achieving these aims would not only be beneficial in geriatric hip fracture repair but also and could markedly improve Medicare DRG performance.

Collaborating to build a standard process

One of the first actions of the PSH team was to engage with hospital executives to gain their support in prioritizing the project and in mobilizing health services to organize and participate in the project. Securing this backing paved the way for El Paso clinicians to more readily access essential data and attract willing participants from multiple departments. Key steps in the effort included the following.

Focus on standard-care pathways. Recognizing that the then-current processes were had substantial room for improvement, the team re-engineered clinical pathways and standardized order sets using recommendations and guidelines from the ASA, ASA-PSH, AAOS, Evidence Based Perioperative Medicine (EBPOM), Society for Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement, (SPAQI)and other health authorities. The team recognized that adopting standard order sets would reduce potential variability in care and ensure points of care would be addressed that might otherwise be overlooked or mismanaged.

To inform this effort, the team reviewed institutional data on time from ED presentation to surgery, length of stay (LOS) and costs. Hospital data were used to identify trends, demonstrate effectiveness of care and guide and reinforce institutional process modulation and acceptance.

Multidisciplinary effort. To gain institutional input and buy-in on standardized care, the team collaborated with a wide range of hospital services and stakeholders, including various departments such as the EDs, anesthesiology, surgery, geriatrics/family medicine, nutrition, occupational/physical therapy and discharge planning. This multidisciplinary effort was focused on proactively identifying potentially modifiable barriers to discharge. One such barrier was imperfect coordination between physical therapists in submitting timely disposition recommendations and case-management staff who needed this information to secure insurance approvals for services and to discharge patients to a post-acute setting. The result was delayed insurance approvals that end up prolonging length of stay. Every two to four weeks, educational and other sessions were held to reinforce principles of evidence-based perioperative medicine, including state-of-the-art care coordination models, consensus statements and clinical practice guidelines that collectively guided the pilot’s best-practice treatment pathways and protocols.

Consistent with the PSH concept, the UMC pilot achieved seamless integration of best-practice treatment protocols, while actively engaging key healthcare and other stakeholders (e.g., patients and their families) in educational and other supportive activities.

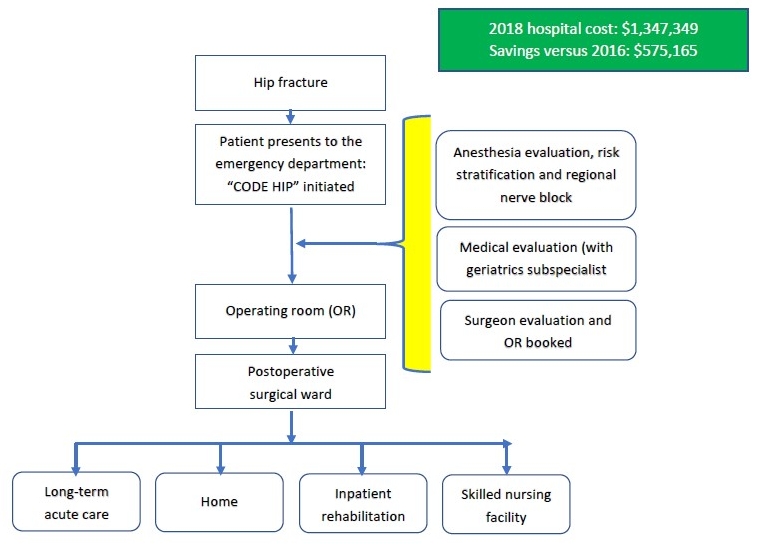

The collaborative effort culminated in the institutionwide implementation of a patient-centric, best-practice pathway for geriatric hip fracture, as shown in the exhibit below.

After: Flow chart of patient care for hip fracture under the Code Hip Pilot Program

Source: University Medical Center of El Paso, 2020

Steps to implementing the pathway. The next step was to operationalize the pathway through system- and evidence-based process re-engineering. As an example, as part of the old process, the anesthesia department saw hip fracture patients the day of surgery. In the new process, anesthesia clinicians were assigned to see the patient at the time they were admitted to the ED and identified as needing surgery. Another example was off-guideline requests for cardiac tests, which were largely expunged with the new process. This change, among other re-engineered processes, allowed timelier and more collaboratively coordinated care, thereby reducing potential complications and unnecessary delays in patient care.

An organizing committee was formed to integrate, coordinate and track adherence to the pathways. Members of this committee included key stakeholders such as orthopedic surgeons, anesthesiologists, family medicine representatives and data analysts. When necessary and requested, ED, physical therapy and case management professionals were eager participants.

The committee was charged with educating the clinicians who were involved on principles of relevant evidence-based perioperative medicine precepts to and then motivating them to adhere to protocols. Another charge was to secure and maintain ongoing executive-level endorsement. Key internal and external experts and hospital personnel, as well as the COO, were tapped to lead this communication effort, which helped in identifying and promptly address issues and concerns.

How financial leaders can help

Financial leaders can help facilitate a perioperative surgical home (PSH) pathway by recognizing that minimal investments in such an approach can create an immense return. For example, funding to hire a nurse practitioner to aid the surgeon in guiding patients through a PSH process would result in greater compliance in protocols, thereby decreasing complication rates, reducing LOS realizing additional cost savings.

Finance leader also can play a pivotal role by working/negotiating with insurance carriers to promote earlier decisions in patient disposition, or to pre-arrange disposition options with locations that have high-standard evidence-based medicine protocols in place, further guaranteeing high-quality care and reducing complication/readmission/death rates.

Implementing a cost-sharing model with a PSH pathway also can motivate buy-in and compliance from participating services. For example, a percentage of the realized savings can be redirected to each service line as compensation for a job well done.

“Code Hip.” This slogan became a rallying cry and cause célèbre for the hospital—it elicited widespread interest, enthusiasm and motivation and set the stage for acceptance. To clinical staff, it meant reduced morbidity, while to the operational and financial staff, it meant improved throughput and improved DRG and episode-of-care (EOC) performance, respectively.

With this acceptance came adherence to the pilot team’s protocols and pathways — a critical ingredient for predicted results to become reality. As depicted in the previous exhibit, whenever a patient 55 years or older presented with a hip fracture, the event would trigger a group page that simply stated, “Code Hip” and the room the patient was to be found in. Services were mobilized in a carefully orchestrated manner. The orthopedic surgeon, for example, after receiving the page would quickly evaluate, consent and create a treatment plan. Anesthesia would evaluate and provide preoperative recommendations for patient optimization as well as pain control interventions, including the completion of a regional/pain block in the ED. As a result, need for narcotics was avoided or reduced, thereby also reducing risk for pre- and post-operative and delirium.

Family medicine would meet the patient early and form a plan to efficiently move the patient towards a quick and safe discharge after surgery by taking inventory of, and adroitly managing, comorbidities. All the other service performed their respective duty in an organized fashion, all with the goal of efficient, effective and timely care.

Patient and family education was delivered by multiple hospital services, including orthopedics, family medicine, geriatrics and anesthesiology, and targeted printed materials reinforced understanding of their injury, illnesses and healthful practices.

Overview of findings

To assess the pilot’s effectiveness, we reviewed de-identified data from the hospital’s trauma and financial databases, using International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9/ICD-10) criteria, for patients aged 55 years and older with hip fractures and admission dates from Jan. 1, 2015 (baseline year) through Dec. 31, 2018 (intervention period).

Results of the baseline 2015 cohort, on average, were as follows:

- EOC inpatient cost: $15,885

- Wait times from ED admission to surgery: 47 hours

- Hospital length of stay: 4.6 days

- 30-day readmission rate: 7%.

In comparison, the pilot cohorts in 2016, 2017 and 2018 achieved the following results, respectively, relative to the 2015 baseline:

- Reduction in EOC inpatient cost: $982, $2,627 and $1,703

- Reduction in lag between ED admission to surgery: 15, 28, and 26 hours

- Reduction of hospital stay: 0.09, 0.51 and 0.67 days

- Reduction in 30-day readmission rates: 3% ,4% and 5%

Observed in-hospital mortality rates in 2016, 2017 or 2018 also were no higher than in the 2015 baseline year.

Outcome Measures El Paso Hospital Hip Fracture Pilot

Variable |

2015 (baseline) |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

Number of cases |

119 |

129 |

101 |

95 |

|

Average age, year |

77.0 |

78.0 |

78.4 |

79.2 |

|

Females, percentage |

66 |

64 |

70 |

68 |

|

Average length of stay, days |

6.40 |

6.31 |

5.89 |

5.73 |

|

Total annual hospital cost, dollars |

$1,890,373 |

$1,922,514 |

$1,339,094 |

$1,347,349 |

|

Average lag time from admission to surgery, hours |

47 |

32 |

19 |

21 |

|

30-day readmission rate, percentage |

7% |

4% |

3% |

2%

|

|

In-hospital mortality |

3% |

2.3% |

1% |

1% |

Source: University Medical Center of El Paso, 2020

The pilot program was also associated with increases in rates of discharge to specialty inpatient rehabilitation hospitals (IRHs), long-term acute care (LTACs) facilities and skilled nursing facilities (SNF) compared with more frequent discharges to home in the baseline period. It is possible that these home discharges were more apt to be readmitted for issues that IRHs, LTACs and SNFs are generally able to address (pain, nausea, fall-prevention). If so, re-engineering of the home-based recovery process might yield further improvements.

The pilot was viewed as a successful proof-of-concept initiative, which continues to evolve with further refinements to both the operational and clinical care pathways. With any project, as the process moves forward there are new insights garnered that help propel the work forward and improve results. Since the pilot began, for example, an ASA-PSH tool (handout) has been created and is being used to help patients and their families navigate through, and better understand, their surgical journey.

The pilot was a proof-of-concept initiative involving a narrowly defined patient cohort (geriatric hip fracture) within a single specialty (orthopedic). Existing resources were deployed, and the incremental workload was absorbed by highly motivated clinical and nonclinical team members. Expanding the initiative to encompass the entire orthopedic service, or other service lines, would likely require additional resources in the form of people, office space and technology, although costs-avoided might provide substantial offsets or, perhaps, be associated with a return on investment.

The promise of Perioperative medicine and the PSH approach

In addition to improving health outcomes and patient experiences, careful deployment of evidence-based perioperative medicine precepts in a cultural environment that can support a PSH, can help reduce superfluous and expensive tests. The healthcare organization can then redeploy saved resources to activities aimed at optimizing modifiable risk factors, which have been shown to reduce complications and mortalities. In this way, and organization can avoid CMS penalties and instead gain incentive payments, improve DRG yields, and develop strong value-based contracts with payers.

Achieving the collaborative and coordinated culture that promotes a multidisciplinary approach has other clear benefits, which include attracting patients and supporting clinician recruitment and retention. Moreover, in our case, key outcomes measures led us to consider applying for designation as an IGSF Center of Excellence.

Future studies are needed to corroborate our findings in other treatment settings and patient populations. Nevertheless, the UMC El Paso Hip Fracture Pilot program serves as a proof-of-concept for cooperative and effective multidisciplinary care programs, that when supported by the right project and data management resources, can yield positive results.

Footnote

a See American Society of Anesthesiologists, Perioperative surgical home (PSH), 2020.

Defining characteristics of PSHs

The perioperative surgical home (PSH) concept is aligned with the new “volume-to-value” care paradigm shift that is consistent with contemporary CMS and commercial payment models, such as the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, Mandatory Episode Payment Models and Medicare Shared Savings program. The 2020 PSH Cohort under the PSH Learning Collaborative led by the American Society of Anesthesiologists, includes 88 physician groups, health systems, academic medical centers, and other institutions piloting care for a range of therapeutic areas, including bariatrics, cardiac, gastrointestinal, general-surgery, obstetrics-gynecology, and urology.

In general, a perioperative surgical home (PSH) is a team-based, patient-centric care model that emphasizes patient satisfaction, value and reduced costs. To create a PHS, hospitals often must mobilize a comprehensive suite of resources, services, and tools to foster team-based care via improved consultation, education, engagement and economics. The PSH model helps to optimize coordination of care, in a patient-centered, physician-lead, team-based manner. Each care episode in a PSH model is viewed on a continuum beginning with the decision to have surgery and culminating in care beyond discharge.

The key triad of PSH objectives, which are aligned with the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Triple Aim, are:

- Enhanced patient health and experience

- Enhanced healthcare access and delivery

- Reduced costs

Benchmarks include improved operational efficiencies, decreased resource utilization, a reduced length of stay (LOS) and readmissions, and a decrease in complications and mortality. These endpoints can be accomplished because PSH care models emphasize evidence-informed care pathways that promote safety, quality and faster recovery.

Overview of PSH clinical assessments

University Medical Center (UMC) of El Paso, in El Paso, Texas created its perioperative surgical home by adopting standardized, best-practices (AAOS and other consensus-guideline‒based), patient-centric protocols, as follows.

Preoperative protocols (procedures limited to . The projected periods for the protocols listed below were required response times, which ran in tandem (parallel) and not in series. For example, anesthesia had to see a patient within two hours of the Code Hip page. And family medicine was required to evaluate patients and have admission orders within four hours of the Code Hip page. These projected intervals facilitated:

- Timely management of medical conditions before surgery

- Expeditious and effective pain control (with regional nerve block to avoid opioids where possible)

- Avoidance of postop delirium and other potentially challenging and costly complications.

Here are the five protocols and their essential components.

1. Surgery protocol (