Healthcare’s financial recovery after COVID-19 depends on data and evidence

Dan Hermes

John Cherf, MD

Controlling variation in costs for surgical procedures presents one of the greatest financial opportunities for hospitals and health systems today. Looking at supply costs is a good place to start.

As the nation adapts to new realities created by the ongoing presence of the coronavirus and begins to arrive at a new normal, it will be incumbent on hospitals and health system to institute the new steps and processes that will secure their own financial recovery. Of course, those efforts necessarily will include fully resuming elective surgeries. But it cannot stop there. Hospitals also will face an economic imperative to optimize the financial performance of each surgical procedure moving forward.

A hospital’s financial recovery will be less about hand-selecting the most profitable cases and more about looking at every procedure and driving out variation and cost. Very few hospitals and health systems completely understand what drives expenses for procedures. Recovery will rely on instituting process improvements that reduce variation, including use of supplies to help ensure cases across the surgical spectrum reflect sound financial principles and performance.

The need for a new focus on supply costs

If there is a silver lining with COVID-19, from an operational standpoint, the pandemic has brought a sense of urgency to supply chain issues. Today, 40% to 60% of a hospital’s total supply spend comes from physician preference items (PPIs).

PPI utilization is not symmetrical across service lines. We recently reviewed PPI spend from more than 300 hospitals within 51 health systems, and then ranked those service lines that are more implant-intensive (i.e., involving a higher use of implant PPI), as shown in the exhibit below. From a financial perspective, some of the procedures within these service lines are also implant-sensitive (i.e., where procedure margins are dependent on controlling PPI costs).

Physician preference item (PPI) spend by service line

|

Rank |

Service line |

Percentage of PPI spend |

|

1 |

Orthopedics |

20% to 25% |

|

2 |

Cardiac Services |

20% to 25% |

|

3 |

Interventional & Vascular Services |

15% to 20% |

|

4 |

Surgical Services |

About 15% |

|

5 |

Spine |

10% to 15% |

|

6 |

Neurology |

About 5% |

Source: Based on PPI spend from 350 healthcare facilities, Lumere Analysis 2021

Reining in this spend can be challenging, but it is not impossible when there is collaboration between supply chain and clinical teams. These partnerships should be founded on the exchange of clean, accurate real-time data that pinpoints factors affecting the cost, quality and outcomes of surgical cases. Combining the operational competencies of traditional supply chain with the expertise of clinicians provides a platform for success.

The goal should be to build an evidence-based and clinically integrated supply chain strategy that optimizes the cost and utilization of medical devices and improves the performance of surgical cases. Such a strategy has three primary areas of focus.

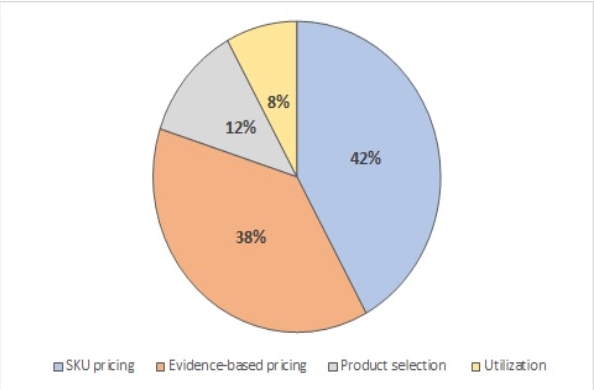

1. Identify new opportunities to reduce costs on medical devices using clinical evidence. Traditionally, hospitals have focused on reducing price at the stock-keeping-unit (SKU) level to achieve savings on medical devices, but this approach can only take an organization so far. On average, improving SKU pricing accounts for 42% of savings. SKU pricing involves reviewing the cost of each product and negotiating an appropriate price on a product-by-product basis rather than taking discounts on groups of products or product portfolios. This strategy requires an understanding of when premium prices are justified (e.g., based on outcomes evidence), and where organizations should expect the same price because there is no clinical differentiation between products. An example of reducing SKU pricing strategy is to negotiate a 3% discount on a specific implantable device, such as the polyethylene (plastic) patella (kneecap) that is part of a knee replacement.

The remaining potential savings are based on clinical considerations, including evidence-based pricing, selection of proper products and appropriate utilization (see the exhibit below). This area of focus presents a huge opportunity for improving the efficiency of cases and driving out costs, but it requires data and clinical evidence.

Supply chain savings potential by strategy

Source: Cherf, J., and Kerr, S., “Evidence-based savings opportunities exist with TJR devices,” AAOS Now, January 2019.

Evidence and data can help an organization identify situations where contemporary research and clinical practice guidelines no longer support the use of a given technology or device. The product may not be a bad decision for the patient, but the choice drives up cost without an added benefit.

A good example is the use of continuous passive motion (CPM) machines after extremity surgery, particularly knee replacement surgery. As much as many clinicians once believed these machines could help patients regain motion and function of their operated joints, this view was not supported by research published in the clinical literature, which found no meaningful impact of using CPM machines. As a result, these devices are no longer part of postoperative treatment for knee replacement surgery.

Using evidence and clinical outcomes data is a more sophisticated approach to managing pricing and opens the door for teams to pursue more aggressive sourcing strategies. Examples of such data-driven strategies include:

- Restricting the use of devices and suppliers by creating device and/or supplier formularies

- Reducing variation in utilization

- Establishing partnerships between clinicians and supply chain executives to promote appropriate use by matching products to demand and purpose (i.e., selecting the right device technology for the right patients based on evidence)

Using data gives hospitals an effective means to standardize and achieve financial savings without affecting outcomes and satisfaction. The third example in the data-driven strategies also is integral to point two, described below.

2. Collaborate with clinicians on product selection and utilization decisions to optimize cost, quality and outcomes. Clinicians are becoming more attuned to the financial pressure hospitals face and often want to partner on cost-saving initiatives as long as patients are not adversely affected. To effectively gain physician support, it is important to keep in mind they are empirical thinkers and tend to be competitive with their peers. By providing real-time visibility into cost per case and data on variation and outcomes, a supply chain team usually can persuade clinicians to switch products when appropriate. Most physicians will be open to self-correcting their behavior and preferences if they are presented with evidence that they are outliers or are practicing at the bottom of the curve.

For instance, in the past, surgeons routinely used antibiotic-loaded cement in orthopedic cases as a preventive measure against postoperative infection. It did not hurt the patient, and in some cases it helped. Clinical evidence linked to short- and long-term complications (e.g., post-operative infection), peer use and pricing indicated that antibiotic cement should be used only in cases associated with a higher risk of infection or on patients that present with a high-risk of infection (e.g., up to about 20% of total joint cases).

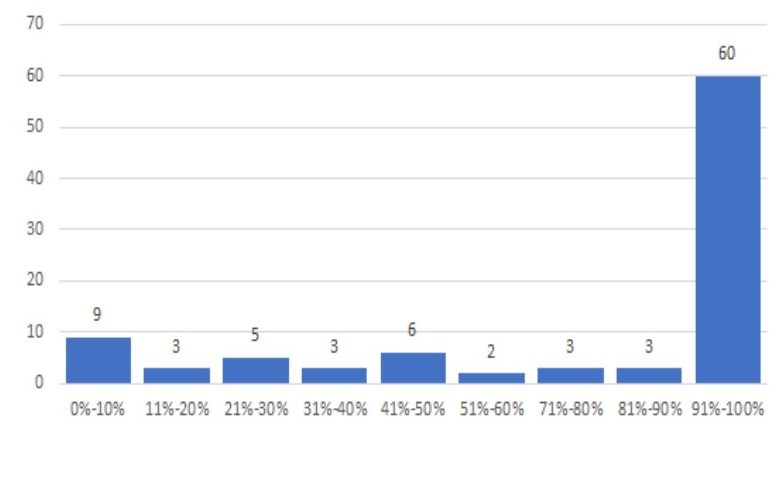

At one large health system in the Southeast, physician utilization of antibiotic-loaded cement was consistently varying from 0% to 100% . After clinicians agreed to follow evidence-based guidelines to adjust their use of antibiotic loaded bone cement, this health system reduced the clinical variation of this product and lowered its annual cost for the product by $613,000.

Variation in antibiotic-loaded bone cement use for total knee replacement

Source: Deidentified data set for a health system in the Southeast, Lumere Analysis, 2020.

3. Explore ways to capture accurate supply information during clinical documentation. Given healthcare’s increasing reliance on technology and data, it is imperative for healthcare organizations to collect data cleanly and accurately from every possible source to be able to understand the impact of device utilization and variation on total costs. The electronic health record (EHRs) is an important repository of a broad variety of data for this purpose, including, for example:

- Purchase order history

- Item master data

- Clinical attributes

- Contract item data

The fastest way to end a conversation with a clinician is by presenting a slide with inaccurate data. Aggregating data from multiple sources and presenting it in real time is critical to advancing the clinically integrated supply chain.

This point is exemplified by the work completed by a large academic medical center in the Southeast. Recognizing that the data it used to identify savings opportunities was often flawed or incomplete, the health system focused on cleaning up its data inputs to better support accurate, actionable outputs. This effort enabled the health system’s supply chain team to engage with clinicians in sourcing and utilization conversations informed by clear evidence. As a result, the supply chain team and clinicians used a trusted data source and were able to quickly realize savings with no adverse impact on patient outcomes.

No time for a narrow focus

Healthcare’s road to financial recovery cannot be paved by focusing solely on high-margin surgical cases. To pursue such a course is neither ethical nor financially viable. Instead, the road forward should be designed around the industrywide adoption of evidence and outcomes data to advance clinically and financially integrated supply chains, applying this to all procedures across all service lines.

The COVID-19 pandemic put the spotlight on supply chain inefficiencies. Hospitals and health systems should use this opportunity to build a better supply chain for the future: one that integrates clinical evidence with operational efficiency. The ability to achieve such a result may prove to be a silver lining of COVID-19.