Elective surgery does not mean optional surgery: How to recover from the impact of canceled procedures

Lessons health systems have learned because of the COVID-19 pandemic will provide the building blocks to the recovery, including the return of “elective” procedures, many of which are vitally important to patients’ well-being.

In the last two weeks of March, the vast majority of health systems across the country cancelled or postponed “elective” procedures as a means to prepare for an anticipated surge of COVID-19 patients. Reflecting in his daily public letter to faculty and staff on the operational changes New York-Presbyterian Health System was making to confront COVID-19, wrote Craig Smith, chair of surgery, March 20:

Nothing would give me greater pleasure than to apologize profusely in a few weeks for having overestimated the threat. That would mean we never exceeded capacity, and that mortalities and morbidities rarely seen in non-pandemic circumstances were avoided. The next month or two is a horror to imagine if we’re underestimating the threat. So what can we do? Load the sled, check the traces, feed Balto, and mush on.

Although the nation’s decision to cancel electives was effective in preventing the type of mass casualty event that was feared — where bed supply would fall short of projected demand — the cost to U.S. health systems has been cataclysmic. New research suggests that U.S. health systems, which operated on a 2.1% average margin in pre-COVID-19 times, are losing $60 billion per month during the COVID-19 crisis due to volume reductions.

Yet the impact of the cancelation of electives extends far beyond hospitals’ finances: It cuts to the health of our nation.

The true impact of the hiatus from elective procedures

To appreciate the gravity and scope of health system leaders’ efforts to revitalize their organizations, we must first objectively understand the clinical and financial dimensions of this crisis. An analysis of procedure volumes at 51 health systems representing 228 hospitals across 40 states found that the number of unique patients who sought care in hospitals during a two-week period between March and April 2020 dropped 54.5 % compared with the same period in the prior year.[a]

If we look at only the top 10 inpatient procedures and surgeries — those encounters that drive over 50% of health system revenue annually — the crisis becomes even more stark. The exhibit below shows that three of the highest contribution margin procedures for hospitals — the “hips, knees and spines” trifecta — all saw declines of between 79% and 99%.

Volume changes for top 10 inpatient surgeries and procedures

| Primary knee replacement | -99% |

| Lumbar.thoracic spinal fusion | -81% |

| Primary hip replacement | -79% |

| Diagnostic catheterization | -65% |

| Diagnostics | -60% |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | -44% |

| Fracture repar | -38% |

| C-section | 2% |

| Regular delivery | 1% |

| Mechanical ventilation | 24% |

Source: Strata Decision Technology, May 2020. Data current as of May 11, 2020

Percentages represent changes year-over-year from a two-week period in 2019 (March 24 to April 6) to the corresponding two-week period in 2020 (March 22 to April 4). Care family definition per Sg2 Care Grouper™

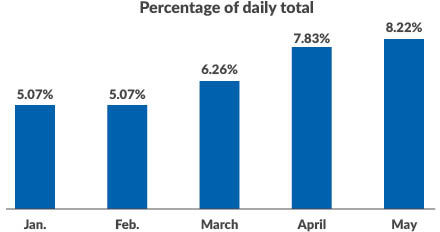

These volume decreases accompanied changes to payer mix, following the rise in the national unemployment rate. In the cohort of hospitals studied, the percentage of encounters involving patients who lacked insurance grew from 5% in January to 8% in May (preliminary results), a 62% increase.

Percentage of self-pay encounters by month

Source: Strata Decision Technology, May 2020. Data current as of May 11, 2020

Combining a precipitous decline in procedures with a material shift in payer mix complicates an already challenging reforecasting exercise. As leaders project the time frame by which their organizations will break even on operations, they must overlay a higher allowance for uncollectable accounts onto forecasts of reduced procedures.

The burden of avoided care

Even more than posing a financial challenge for hospitals, the sharp reduction in patients accessing care bears grave clinical implications for patients. If we examine the decrease in access to care by procedure category, we see huge declines in access both for life-threatening illnesses such as congestive heart failure (-55%), heart attacks (-57%) and stroke (-56%) and for chronic diseases such as hypertension (-37%) and diabetes (-67%).

Change in inpatient and outpatient encounters by clinical care family

| Cataracts | -97% |

| Sleep apnea (often a harbinger of cardiac disorders | -91% |

| Glaucoma | -88% |

| Osteoarthritis | -88% |

| Coronary heart disease | -75% |

| Chronic otitis media and sinusitis (ear/sinus infection) | -75% |

| Hypertension | -74% |

| Hyperlipidemia | -74% |

| Neuro pain and neuropathy | -71% |

| Care for diabetes | -67% |

| Asthma | -62% |

| Ischemic stroke | -56% |

| Congestive heart failure | -55% |

| Chest pain (non-cardiac) | -44% |

| Prostate cancer | -44% |

Source: Strata Decision Technology, May 2020. Data current as of May 11, 2020

Percentages represent changes year-over-year from a two-week period in 2019 (March 24 to April 6) to the corresponding two-week period in 2020 (March 22 to April 4). Care family definition per Sg2 Care Grouper™

Furthermore, the screening and prevention category, recognized as important but not sufficiently emergent to be permitted under most elective procedure freezes, suffered a steep volume loss: Breast health, gynecologic wellness and gastroenterology screenings all declined by more than 75%.

Such an environment, where procedures surrounding critical illnesses are canceled and patients are actively avoiding emergency care for fear of contracting COVID-19, exhibits all the hallmarks of a public health crisis. So far, most of the data indicating the deleterious effects of COVID-19-driven care avoidance has been anecdotal — such as surgeons at Northwell Health citing amputations on patients that might have been avoided had the patients been treated sooner. But the care gaps created by COVID-19 will almost certainly become a dominating narrative in the months to come.

Recommendations from the field

So where do we go from here? How do leaders plot a path to financial viability, while remaining vigilant against current and future COVID-19 outbreaks? How do executives integrate the wartime innovations they produced during the pandemic into their operations moving forward? Here are some strategies gleaned from our conversations with health system leaders.

Amplify care teams through remote patient monitoring. As emergency departments (EDs) in hotspot markets became flooded with COVID-19 patients, executives were confronted by a number of critical challenges around capacity and supplies, including:

- Preserving inpatient beds for those most in need

- Securing adequate staff coverage amid an insufficient supply of caregivers

- Sequestering COVID-19 patients from those in the hospital for other ailments

In response, several health systems quickly leveraged remote patient monitoring (RPM) solutions, whereby COVID-19-positive or presumptive positive patients are discharged with a set of Bluetooth-connected devices. From their own beds, each patient’s oxygen saturation and temperature are continuously transmitted to a telehealth nurse, who is thus equipped to determine whether a patient’s clinical conditions merit inpatient observation.

As health systems experienced the dramatic improvement in nurse-patient staffing ratios that was achieved through the use of RPM (one system citing an improvement in the ratio of nurses to patients from 1:15 to 1:65), many have started aggressively rolling out RPM across their broader clinical enterprise, viewing it as an inextricable part of their care delivery strategy moving forward.

ChristianaCare based in Newark, Delaware, offers a noteworthy example: The health system leveraged its versatile RPM platform to expand its care team’s ability to support COVID-19 patients at home and for virtual care management. “We rapidly scaled our virtual operations, and now that same platform is being used to support care teams working to restart elective surgeries and procedures,” Randall Gaboriault, chief digital and information officer, told us. “This model did not just change the way we work; it changed the work.”

Re-envisioning the digital front door. In early March, health system call centers became inundated with patient requests. Queries ranged from checks on symptoms to proactive efforts to schedule previously postponed care to requests for information on COVID-19. Health systems best poised to communicate with their patients at scale had already made substantial investments in their digital front doors, having integrated an array of self-service functions, including scheduling, asynchronous messaging, personalized content and automated check-ins.

Aaron Martin, executive vice president and chief digital and innovation officer at Providence St. Joseph Health, said: “As the pandemic accelerated, the digital front door became the central entry point by which patients interact with their systems. COVID-19 demonstrated in stark terms for health systems the problems with the off-line, fee-for-service business model in which they have limited digital engagement with their patients between episodes of care. The digital front door is now critical as health systems will need to create an engaged digital health experience with their patients, which will drive growth, efficient care delivery, new revenue streams, and make managing population health and capitation at scale possible.”

Recouping lost volumes through virtual care. Supported by expanded funding and the relaxation of certain privacy regulations, the COVID-19-driven explosion of telemedicine is well-documented. Yet the range of virtual care use cases extend far beyond conventional definitions. Before elective procedures began to be canceled due to COVID-19, providers were recouping critical revenues by providing virtual post-surgical checkups for procedures. These practices laid the foundation for a vigorous elective phase-in by offering pre-surgical consultations during the months of April and May and helped launch proactive virtual prevention and wellness campaigns to keep clinicians productive.

“CommonSpirit Health has expanded access to care and provides more than 10,000 virtual visits a day in a range of clinical areas,” said Rich Roth, chief strategic innovation officer at CommonSpirit Health, Chicago. “We have also launched automated tools (chat bots, screening tools), which are being used by thousands of additional individuals, each working to educate and triage community members to effective care settings and helping to safeguard caregivers in our communities.”

Pinpointing interventions for the most vulnerable through targeted analytics. In the past two years, no digital health subsector has had more meteoric expectations assigned to it than clinical artificial intelligence. With the onset of COVID-19, many healthcare organizations have found concrete use cases for these technologies in identifying those greatest at risk of experiencing severe COVID-19 outcomes, determining which interventions are most likely to work for which patient populations and informing the redeployment of clinical resources to where they are most urgently needed.

“Leveraging a predictive analytics product, we’ve been able to proactively reach out to those patients in our population who are most vulnerable to COVID-19, while offering our employer clients the ability to mitigate the impacts of this disease on their population,” said Vickie Rice, vice president of strategic analytics at CareATC in Chicago.

Radical cost reduction through administrative process automation. Despite recent data suggesting encounters are rising, most health system leaders do not expect volumes to meet pre-COVID-19 levels in the near-term. In this context, many executive teams have modified their business models to do more with less. Given the need to maintain a robust clinical workforce, healthcare leaders have looked more closely at their administrative structures to find cost- optimization opportunities.

“Our health system has been automating transactions around our consumer self-service strategy for years,” said Chad Brisendine, CIO of St. Luke’s University Health Network, headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. “With the onset of COVID-19, the need to further automate has never been more important. St. Luke’s has expanded its automation work to include virtual care processes.”

Safeguarding the lifeblood of the organization by optimizing payments. For many health systems, the COVID-19 crisis has been characterized by a major shift in procedure mix, an increase in the proportion of self-pay patients and a change in clinical site-of-service from in-person to virtual. These changes have introduced major revenue cycle challenges for health systems at a time when maximizing revenue is critical to survival. As leaders prepare for a transformed healthcare delivery landscape, they must realize that the payments reality has changed as well. Administrators may emerge from this crisis to find that many of the traditional billing and collection practices that served them well previously are outmoded. As systems chart their courses back to profitable operations, they will find it beneficial to invest in a secure and scalable payments infrastructure that includes text-to-pay functionality, point-to-point encryption and optimized mobile and online payments experiences.

Moving forward with demonstrated successes

As elected officials and healthcare leaders across the nation observed a European health system stretched beyond capacity by COVID-19, they acted, almost in unison, to cancel elective procedures. This decision helped U.S. health systems avoid the nightmarish scenario observed elsewhere in which physicians were forced to make the harrowing choice of who would receive an available bed and who would not.

Yet this decision also dealt a crushing financial blow to our delivery system and severely curtailed access for patients in need of care. As executives begin to phase back in scheduled procedures, while preparing for a second potential wave of COVID-19 in the Fall, they would be well served to incorporate best practices gleaned from leaders in virtual care, remote patient monitoring, payments, digital front door, and predictive analytics.

Footnote

[a] This article draws upon data from Strata Decision Technology’s National Patient and Procedure Volume Tracker, which has been updated weekly between May 11 and May 26. Future iterations will incorporate forthcoming updates.