Steve LeFar talks about the implications of care deferrals due to COVID-19

The economic impacts on hospitals and health systems from deferred healthcare as a result of COVID-19 was already a major concern in the first year of the pandemic. Yet at that time, no one could have guessed that it would continue to be a concern two years later.

At the very time when things seemed ready to pivot to “normalcy,” surges in coronavirus variants forced hospitals to again divert critical inpatient resources to these patients, and again defer “elective” services for other patients.

The nation continues to face a very real potential problem, said Steve Lefar, senior vice president for Chicago-based Strata Decision Technology, who was among the first to call attention to the looming threat of essential care deferred. Lefar is the executive director of and oversees a massive industry data-sharing platform and network, StrataSphere, a data collaborative that generates comparative analytics for users and has also been used to provide insight into the impact of COVID-19 on health systems. And the data tell a clear story, he said, about shifts in patient care for potentially vulnerable populations. But Lefar also suggested many questions remain about the extent to which these patterns portend an imminent new crisis from rising populations of severely ill Americans.

Q

In June 2020, you and Ezra Mehlman wrote an article that looked at the potentially dire consequences of the deferral of “elective surgeries” as a result of COVID-19. Now, after almost two years, it seems the problems associated with deferred care are far from solved. Can you talk about what has happened since June of 2020? How has this issue evolved, and what are hospitals and health systems doing to address it?

Lefar

We are able to see this happen in almost real time, using complete and current data curated from a cohort of more than 400 health systems and over 2,000 hospitals. And what we have seen is that, starting from when everybody had the collapse in volume, as the first wave hit in March 2020, we have a trend of much lower than normal volumes, which continued right through August of 2020. And it’s really been ongoing across all settings. The trend is even more pronounced when we pull out the COVID-19 volumes.

Here are some facts about what has happened versus the baseline year of 2019: Inpatient volumes were down 14.7% in 2020 and 13.4% in 2021 excluding COVID-19, and volumes were a little stronger with COVID, being down 9.6% and 6.3% in those two years, respectively.

But the non-COVID volumes are still way down.

What’s happened with the emergency room is even more profound: Without including COVID cases, ED volumes were down 21% in 2020 and 15% in 2020, compared with baseline — and they were down a little less with COVID cases.

And even outpatient volume, when you strip out COVID vaccines and COVID tests, was down 10% in 2020, compared with 2019. But it was up 8% in 2021, so some of it’s coming back .

Q

Can you give some specifics of what you are seeing in the data?

Lefar

One particularly interesting story is about rapid adaptation and deferred care, either due to triaging or changes in provider and consumer behavior, which may or may not be permanent.

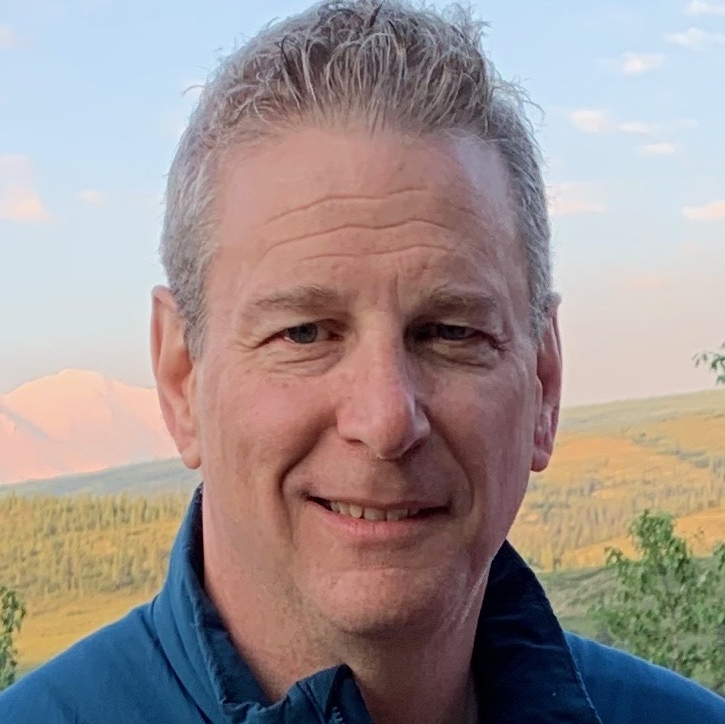

Providers have done a remarkable job in adapting through shifting things to the outpatient area — and particularly the important things like cancer therapies, as well as using telehealth and remote monitoring. For example, prostatectomy for both BPH [benign prostatic hyperplasia] and prostate cancer in the inpatient setting was down 7% in 2020 and down 43% in 2021. But on the outpatient side, it was up 10% in 2020 and up 36% in 2021.

So you’re seeing this shift to outpatient. And when you strip out BPH (which is generally not life threatening) and just look at the prostate cancer, those procedures were up even more. Clearly, hospitals are triaging things that are more serious and being really effective.

Knees [replacement, revision], on the other hand, are staggering. Some could argue it’s elective, but patients are unlikely to see it that way. Knee procedures were down on the inpatient side, 44% in 2020 and 65% in 2021. But in the outpatient area, they were up 50% in 2020 and 123% in 2021. So there’s been a massive shift on the procedure side.

Primary knee replacement, prostatectomy and lumbar thoracic spinal fusion volume, 2020 and 2021

Q

What’s been happening with deferred care?

Lefar

When we look at deferred care, we see certain volumes have just disappeared, and it will be interesting to see when they come back, if ever. Although consequences seem unavoidable, the full impact has yet to be measured.

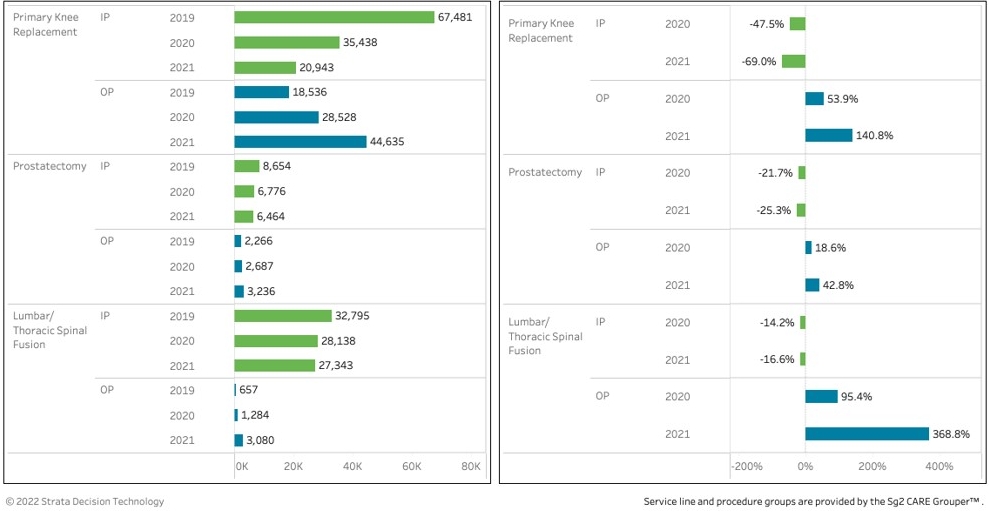

You look at things like screening mammography, which are mostly outpatient: Those outpatient numbers were down 8% in 2020 and 12% in 2021. They haven’t come back — so where are they? And then you see a bit of a corresponding decrease in lumpectomies, which would follow from the reduced mammography and also are almost all outpatient. Those were down 8% in 2020 and 5% in 2021. So there’s clearly some deferral in care there.

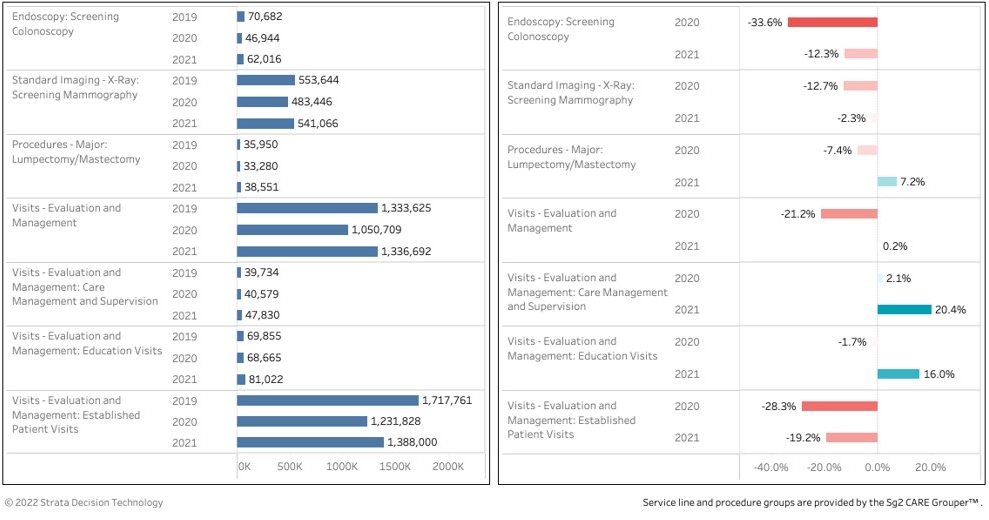

Screening and evaluation visits, 2020 and 2021 compared with 2019 baseline

The area that’s a crazy enigma to me and of real concern is cardiac care. Who knows if it’s behavioral change, if the cases went away, or if we were all cloistered in our homes and had reduced rates of symptoms? But it’s a fact that the volumes were just not there. If you look at noncardiac chest pain, it’s down by a huge amount. And overall, in the ED and inpatient care, congestive heart failure [CHF] and heart rhythm issues seem to be following the same pattern. Even heart attacks are substantially down, which then causes things like stenting [PCI] to go down dramatically. Ablations are tracking close to normal, though, and so are pacemakers. We are also seeing a huge jump in remote rhythm monitoring. So, we have more remote and telehealth care as a net positive, and when people do come in, they are getting needed procedures, but chest pain and heart attacks are puzzling: Either people just didn’t show up and the pain went away, or those people are living on the edge. I have heard that the excess mortality over normal the past two years can’t all be explained by COVID. Perhaps part of it is cardiac events at home.

Cardiac care volume, 2020 and 2021 compared with 2019 baseline

In other areas like diabetes and hyperlipidemia, we definitely see outpatient visits excluding lab — which can inflate volumes — are way down. So while we have tried to keep important procedures going, there has been a concerning deferral in preventive care.

But the implications down the road are hard to assess. People who had known cancer got treatment, but screening in things like colonoscopies were down dramatically in both 2020 and 2021. So we may see consequences of that down the road via disease detection at later stages.

Even appendicitis and hernia were both way down. So did the appendicitis resolve? Did the patients get treatment with antibiotics? Did people just not really need hernia surgery, or are we going to see more severe cases? We just don’t know because we don’t know where they went. But whatever happened didn’t take place inside the health system, and if it didn’t actually happen somewhere, we can expect to see some consequences.

Q

Do you have hard data to show what the ultimate consequences of that might be?

Lefar

Not yet. All I can say is, thus far, we’re not seeing it in the cancer or cardiac volumes; late in 2021, we didn’t see these spikes of delayed care. But we also haven’t seen the admission rates go up for diabetes or things like that, so the downstream impact hasn’t occurred yet or won’t.

Maybe a lot of it went to telehealth for some of this maintenance work and counseling work. But after the initial telehealth boom [where it spiked to 50% of all visits], we don’t really see it continuing in 2021, which now is at about 3% to 8% inside health systems. Patients are still having office visits and those volumes are up, so it’s likely that some of it’s been picked up there. But I suspect we have yet to see the outcomes of this deferred care — unless it’s being managed somehow elsewhere, outside the health system —because it could take a few years to resolve it.

Amid this uncertainty, however, there are two immediate things finance teams should be doing to help ensure the deferrals don’t lead to bad outcomes.

First, they need to partner or build care management and coaching capacity that can help keep patients on the right track for things like COPD, CHF and diabetes to prevent them from showing up in the ED and the inpatient area, where as a result of rising wage rates, these patients may cause them to lose or go negative margin anyhow. The increasing wage rates may actually push a focus on population health and a drive toward more effective and lower cost care models.

Then, finance teams need to really support value-based efforts in the community with SNFs and home care entities. They are a gatekeeper for avoidable readmissions to the ED, and they can be really valuable. Health systems should help them out. They’re getting destroyed right now with their staffing and wage issues as well.

Q

What’s your prognosis for health systems after all of these challenges?

Lefar

I’m very optimistic about the resiliency that health systems have shown: They’ve been beaten and battered, but the big systems have recovered fairly well. Many are economically almost back to where they were in 2019. I worry about the small or mid-size systems in rural and small markets, though; many are still in real trouble and may need some help.

So we need to continue to watch this issue. We need to sort out how we deal with these small and mid-size health systems and how to fund them. There will probably be some M&A, but we also have an FTC that is watching hospital and health system mergers.

We need to take a long-term systemwide view of the staffing issue we are seeing, because, if you just look at the math, not addressing the staffing supply side could crush the health systems over time, even if other costs are cut as some have suggested is the answer. But otherwise from what I have seen and what I’ve heard from health system leaders, I’m very optimistic: It’s going to get solved. And we all can just pray that what’s happening with the omicron variant right now is the harbinger of things to come — that volumes will come down and we’ll continue to be able to get back to normal.

Even then, however, there’s one last challenge that lies ahead. Let’s assume that volumes don’t return to 2019 levels and we keep shifting to outpatient and home. The trickier clinical issue for the health systems could be higher acuity in the inpatient area, although we’ve predicting that for years, and the kind of staff you will need to take care of those patients. If we keep shifting things to the outpatient side which is great generally, what will be left? And how will you maintain inpatient capacity for issues like a pandemic.

If inpatient volumes continue to dwindle, that’s a national discussion. How much capacity do we need to maintain for rapid startup in the event of another surge of some form or another? The surge capacity of the nation’s hospitals was really only set up for mass casualty events; it was never set up for sustained multiyear surge capacity issues. And I think we will have to work hard at a national level to think about what we will do. Who is going to fund allowing capacity to remain idle while maintaining it at ready state?

One thing for sure is that we’ve learned some lessons from this. We need to have in place a system that can respond to a crisis like this – with the ability to flex up and flex down. That raises important questions. If you’ve shifted things, how do you bring inpatient capacity back online in a week or two? Who’s managing stockpiles of whatever’s necessary? And even figuring that out has to be funded.

If you go back and look at it from the public policy side, we had an opportunity to be way more ready. It wasn’t that long ago there was a whole report from the Center for Health Security about pandemic readiness that frankly everybody — Democrats and Republicans — ignored. No party can claim it was the other’s fault. We ignored a lot of the recommendations and we learned that our public health infrastructure is pretty weak.

Again, the health systems took the brunt of the institutional impact . They can’t leave it to the government to deal with. They need to be proposing and thinking about how to maintain ready capacity, just like the military does it.

How COVID-19 has affected the healthcare workforce

The healthcare workforce was already highly taxed prior to COVID-19, but the impact on healthcare workers as a result of the pandemic has been profound, said Steve Lefar, executive director of Strata Data Science. Lefar also considered the likelihood that workers might suffer a further impact from deferred care on top of that.

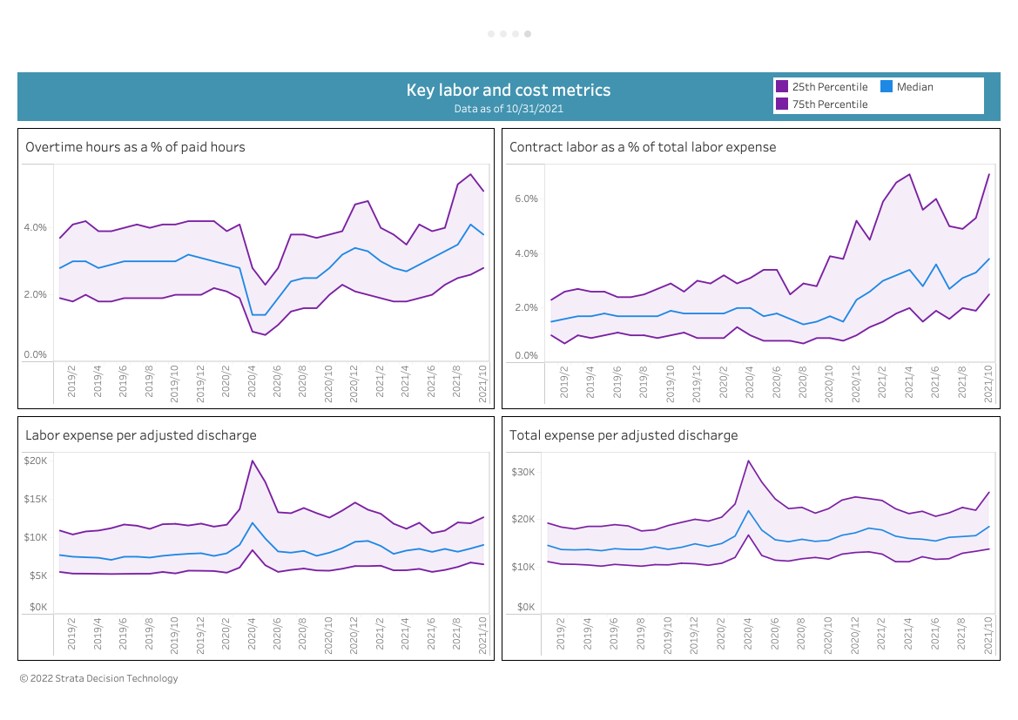

“We looked at things like case mix index and length of stays, and they haven’t moved a ton,” Lefar said. “Length of stay is up a little; case mix is up a fraction. But where we see it is in the cost. When we look at labor expense per adjusted discharge or operating expense per adjusted discharge, it’s gone up.”

Key healthcare labor and cost metrics, 2019-2021

From an average labor expense per adjusted discharge of $9,200 in 2019, this measure climbed to about $11,000 in 2020, and then dropped again to about $9,900 in 2021, Lefar noted. “But total operating expense, which includes everything, has skyrocketed from $16,000 to $20,000 in both 2020 and 2021. So you clearly have higher expenses, higher wages, more contract labor, more purchased services, more supplies. Just from looking at the cost data, these are much more intense patients.”

That situation is one reason many people in healthcare have experienced burnout and left the industry, Lefar said, pointing to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report of six-figure departures from the healthcare labor force and a study by the American Medical Association that found one in five physicians have contemplated leaving,

“We see it in the staffing data from the health systems in near real time,” Lefar said. “Overtime hours are up over 4% of total hours, for a pretty big increase from where it was. Contract labor is up 50% to more than 3% of total labor expense. And it’s rising further. This is not a new problem to COVID-19 in terms of wage rates and people wanting and deserving more.”

This stress on the workforce between departures and the rising costs of labor has made it harder for CFOs and finance teams to balance the budget, have a positive margin and bring in the staff, “if they can even find them,” Lefar said.

“The good news, if any, for overtaxed staff is that inpatient volumes outside of COVID are down,” Lefar said. “Ff that continues, and COVID recedes and we can continue to make progress in moving care toward outpatient care, clinicians may find it a much more attractive work environment and setting to come back into. It’s only days, and you don’t have the patients there overnight. You might be able to move staffing. Time will tell, but we must try”

Lefar’s advice to CFOs? “Work closely with your chief nursing officers to think about how much care could be shifted to the outpatient environment to move 24/7 labor into 12-hour labor and spread it out a little bit more,” he said. “If there’s any silver lining — and there really aren’t many in this whole crisis — it is that shift to outpatient settings. The headlines are understandably all about what’s going on in the ICUs and the critical care units and the lack of respect for our caregivers, which is abominable, but maybe we have the hope of getting them to come back into the outpatient settings to help address this deferred care.”

Other action is needed as well, Lefar suggested. “We know we’ve got this labor issue. But I think we are understating the magnitude of the workforce supply problem. We’re not going to solve that at any wage. We are already seeing investment in building the workforce with training programs and partnerships with technical schools and universities, but more needs to be done. Some leading health systems are deciding to create their own supply by leveraging scale and scope of their facilities, technology and training capabilities with leading academic STEM institutions to create their own degreed educational programs, even including advanced clinical designations (such as PA and MD). Given the wave of retirements and severely limited slots in masters and doctoral clinical programs, is there a choice? The government isn’t likely to do it.”

Lefar characterized it as an existential crisis: “This industry will be broken if we don’t deal with the supply issue. Wages are going up in the rest of the economy. We have to continue to grow our workforce. We have to make it economically and professionally attractive for people to come into healthcare. We also have to fix the abuse of our providers and get patients to leave their politics and anger at the door and not disrespect our providers, because that’s also souring healthcare workers on their desire to dedicate their lives to taking care of us.

In short, health system finance leaders are presented with a massive supply planning issue, Lefar concluded. “Finance teams need to get really granular looking at their volume shift. Where’s it moved? What patient groups and segments are moving? What’s been moving to outpatient? They really need to understand how much care likely was deferred, versus being unnecessary. They need to be much more flexible in how they forecast by adopting a rolling forecast. And they really have to support their clinical colleagues who are looking at all manner of programs to manage demand such as remote monitoring centers, where they can use various available technologies to automate things that can be automated and utilize scarcer clinical staff resources at the top of their skills.”