Why it’s so essential for hospitals to embrace a value-based payment strategy

Few would argue today that U.S. hospitals are facing the most challenging operating conditions in a generation, and perhaps longer. From dealing with myriad severe short-term operating strains, such as workforce shortages, to existential threats to their long-term future, including being cast as the enemy in the fight against rising healthcare costs, hospital leaders are struggling to maintain their organizations’ financial sustainability.

Clearly, hospitals must focus intentionally on all these short- and long-term challenges. Many are doing exceptional work on the short term, but too few are actively preparing for long-term impact of today’s new market realities. Many cling to the fee-for-service (FFS) payment model, out of step with the industry’s transformation, where the path to success is turning unswervingly toward a value-based care model fully focused on improving cost effectiveness of health. (For a discussion of the forces driving this shift, see the sidebar “Forces driving healthcare industry transformation,” below.)

The foundation for effective transformation

Policymakers, pundits and legacy industry participants have long identified value-based care as being key to hospitals’ future success. Yet it sometimes seems that term has as many definitions as the number of lips it’s crossed, given the variety of value-based alternative payment models (APMs) that provider organizations may choose to adopt. Therefore, before pursuing any kind of value-based payment arrangement, a hospital’s executives should be well-versed in the full range of APMs that exist today and how each of these models compare with traditional FFS payment.

The Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCPLAN) has developed a taxonomy that can be useful for understanding the different categories of payment models. Within HCPLAN’s taxonomy, value-based payment makes up category three (APMs built on FFS architecture) and category four (population-based payment) in its payment framework, which the organization describes in its 2022 report on APM methodology and results.a (See the second sidebar below for a summary of the four categories of payment.)

In its report, HCPLAN cites its finding that only 7.4% of actual dollars paid to providers during 2021 qualified as population based.

Even upon adding provider payments from two-sided risk models, that number increases to only 19.6%. Hardly a transformation. Similarly, many of these models have shown limited improvements in quality.

The question is: Why? Based on results of review of those value-based payment models that have produced uninspiring, results appear to have fallen short for three predominant reasons:

- The models are not focused/targeted enough.

- There are minimal, if any, penalties for underperformance.

- They are voluntary, giving organizations the ability to opt out at initial signs of underperformance.

Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that success is possible. Most notably, those organizations that have embraced downside risk have produced outsized improvements on cost and quality measures. Hospital leaders need to understand that incentives are motivators — and that acceptance of downside risk is a powerful motivator for achieving success under value-based payment.

What’s next?

Whether hospitals are willing to acknowledge it or not, for all but the highest-cost, most-complex care, the traditional hospital business model is obsolete. No longer will hospitals be able to rely on an aging population to support volume growth, and rarely will they be able to exert pricing leverage. They will face challenges from capable, well-capitalized competitors in almost every clinical area, and their appeals for relief will increasingly fall on deaf ears of legislators and regulators.

To succeed in this challenging new world, hospitals will require new and, in all likelihood starkly different, strategies. And a key element of future success will invariably be participation in true value-based payment models involving upside-downside risk that enable hospitals to align more closely with consumers and thus reap the rewards of the models’ quality and efficiency.

Given the track record of value experimentation to date, as well as insurers’ seeming disinterest in jointly pursuing honest attempts at sharing the rewards of value creation, hospitals are very likely going to have to pursue value agendas on their own. Building experience through opportunities such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program and understanding and seizing market willingness to move toward direct contracting with employers and/or coalitions may be the most promising places to start.

Despite the naysayers’ chorus — “It’s too expensive,” “We don’t have the data,” “We don’t control the doctors” — we are left to ask, “What choice is there?”

The choice for today’s hospital leaders is either to manage the decline of an industry or to pursue a different path that enables them to continue to effectively serve their patients and communities.

Footnote

a. HCPLAN, APM measurement: progress of alternative payment models, 2022 methodology and results report, 2022.

Forces driving healthcare industry transformation

In the past 15 years, a series of macroeconomic shocks – including a global financial crisis and the prolonged pandemic – have exposed the weaknesses of the legacy U.S. healthcare industry.

Four major forces are driving today’s market trajectory outside the industry’s control, increasingly to the detriment of U.S. hospitals. It therefore is important that hospital leaders take stock of these developments.

1 Demographics. The U.S. population continues to grow and age, but an aging population has proven insufficient to guarantee hospital growth. In fact, and for many reasons, hospital utilization across all age cohorts has decreased materially in recent decades, with this trend accelerating since COVID-19. At the same time, an increasingly sophisticated healthcare consumer, focused on accessibility, affordability and experience, is emerging. Absent long-term loyalty to a physician or hospital brand, patients are acting on their preferences for how, where, when and from whom they receive their healthcare, and they’re increasingly choosing non-hospital options.

2 Economic pressures. Long-perceived to insulate hospitals from downside risk, the weaknesses of the fee-for-service (FFS) payment model were exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic when, almost overnight, losses in patient volumes necessitated service suspensions and a multi-trillion-dollar government bailout for healthcare providers. Long able to justify rate increases, hospitals now face enormous pressure to make price concessions. Faced with declining volumes and little to no ability to raise rates commensurate with cost increases, hospitals’ historical strategy of growing FFS revenue to solve their financial troubles appears obsolete.

3 New competitors. Regardless of their size and scale, hospitals are competing in markets fundamentally different from the markets of two decades ago. Many traditional health systems are pursuing ever greater scale, but floods of capital into non-acute healthcare services are swamping their hospitals’ ability to remain the hub around which care has historically been organized.

Meanwhile, hospitals face competition from new and different quarters. Even as more outpatient services are migrating to lower-cost sites of service, such as freestanding ambulatory surgery centers, more physicians are opting to align with national, private equity-funded practice roll-up companies rather than hospitals. New primary care gatekeepers (e.g., Walmart, Amazon and CVS) seek to control costs in part by steering patients away from hospital-based sites and services. Payers, meanwhile, are growing their ranks of employed physicians for similar purposes.

In short, hospitals find themselves struggling to compete with nimbler, more information-enabled and better-capitalized competitors in all previously profitable areas, while bearing a vastly unequal regulatory burden.

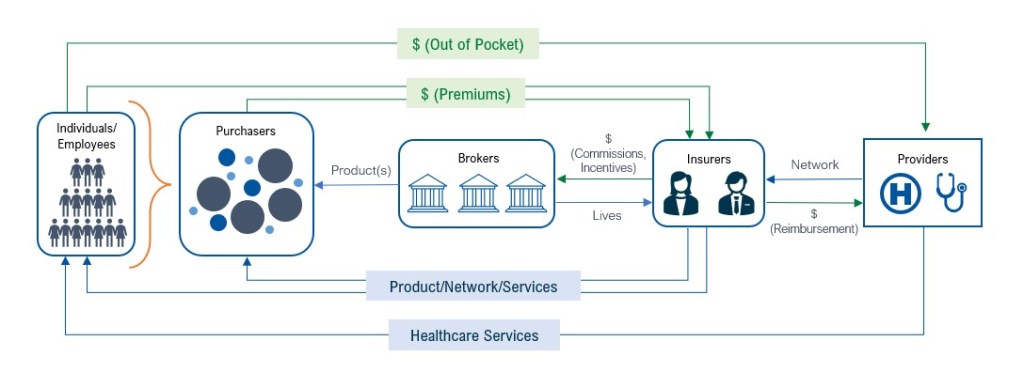

4 Structural obsolescence. The U.S. healthcare industry’s intermediary-laden structure also places hospitals at a distinct competitive disadvantage. Perverse incentives (e.g., brokers are engaged to serve purchasers but paid by insurers) abound, and providers are far too removed from patients, their true customers, to collaborate to define, pursue and achieve mutual objectives of access, quality and cost-effectiveness. Under the current structure, meaningful change from the status quo seems hopelessly elusive.

Current U.S. healthcare market structure

Categories of healthcare payment, from FFS to value-based payment

A 2022 report on APM methodology and results issued by the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network outlines the following four categories of paymenta Here, we examine chief pros and cons associated with each category.

Category 1. Fee for service (FFS), with no link to quality or value

The clear advantage of the FFS approach is in maintaining the status quo and aligning with existing processes. Disadvantages for providers lie with continuing pressure to reduce rates without regard to the cost to deliver services and with the significant risk they face from reduced volume.

Category 2. FFS, with a link to quality or value

This category of payment, quality and value may be addressed in any of three ways.

1 Foundational payments for infrastructure and operations (e.g., care coordination fees and payments for investments in health information technology).Advantages include financial assistance to secure necessary infrastructure for value-based payments. Key disadvantages, however, are that the costs of required investments may exceed payments and that care coordination may reduce FFS revenue without replacement if there is no opportunity to participate in savings.

- Pay-for-reporting (e.g., bonuses for reporting data or penalties for not reporting data). Advantages include incentives to develop competencies in data collection and performance improvement and the opportunity to demonstrate objective quality. There are three key disadvantages:

- Investments in infrastructure are required to collect data.

- The focus on specific measures may detract from other initiatives.

- The approach may be subject to negative public reporting.

- Pay-for-performance (e.g., bonuses for quality performance). The advantages and disadvantages are the same as with pay-for-reporting, with the added disadvantage of revenue loss associated with poor performance.

Category 3. APMs built on FFS architecture

This category comprises APMs that include shared savings, with or without downside risk.

1 APMs with shared savings (upside risk only). Advantages of this approach include the following:

- Opportunity to develop competencies without downside risk

- Interests aligned with referral sources

- Portion of lost revenue captured from improved care coordination

- Failure to participate may cede competitive advantage

The approach also comes with three disadvantages:

- Organizations receive a relatively low percentage of any savings generated

- The model’s complexity and unreliable benchmarks limit savings opportunities

- Initiatives may reduce utilization (and lower provider revenue) associated with non-participating patient populations

2 APMs with shared savings and downside risk (e.g., episode-based payments for procedures and comprehensive payments with upside and downside risk). With this approach, organizations receive a relatively higher percentage of any savings, which increases their incentive to appropriately manage patients.

Disadvantages are that the organization must cover costs associated with managing downside risk (e.g., reinsurance), and it has an elevated risk profile associated with extraordinary costs in small patient populations.

Category 4. Population-based payment

This approach has three layers reflecting degrees of comprehensiveness.

1 Condition-Specific Population-Based Payment (e.g., per-member-per-month (PMPM) payments, and payments for specialty services such as oncology and mental health). This approach has the following advantages:

- Aligns across providers

- Provides reliable income regardless of market changes

- Eliminates costs associated with FFS billing

- Responds to payer/purchaser demands for controlled healthcare costs

Disadvantages are that the provider organization is fully at risk for costs of care in excess of PMPM, and that the approach requires effective team-based care and reliable information derived from data to effectively manage population. There also is exposure to significant losses due to social determinants of health and other unidentified risks in populations.

2 Comprehensive population-based payment (e.g., global budgets or full/percentage of premium payments). The advantages and disadvantages are the same as with condition-specific population health. An additional challenge is that it requires a high degree of coordination with other community providers.

3 Integrated finance and delivery systems (e.g., global budgets or full/percentage of premium payments in integrated systems). This approach also presents the same advantages and disadvantages as the other two population-health-focused approaches, with the added challenge of the managing potential antitrust issues.

Footnote

a. HCPLAN, APM measurement: progress of alternative payment models, 2022 methodology and results report, 2022.