Why effective maternity care requires an innovative, value-based strategy

Tessa Kerby, MBA, MPHE

Rachel Bidgood, MHA

Dana Le, MHA

Maternity care is at a crossroads in the United States.

This service area is fraught with inconsistencies in costs, outcomes and experience, even as the nation faces a declining birth rate and a rise in high-risk births, contributing to a growing national awareness of poor maternal outcomes.a

These factors have created a tremendous need to revamp this service area.

The most effective way to do so may be to address its cost through innovative value-base payment strategies. With the right design, a value-based model for maternity care involving bundled payment can help address these issues by:

- Reducing the rate of C-sections and other birthing interventions while encouraging support for vaginal and vaginal birth after cesarean deliveries

- Improving outcomes for patients by lowering risk of infections and shortening recovery time

- Expanding the use of lower-cost resources, such as midwives and advanced practice providers for prenatal visits

- Improving patient satisfaction through better care coordination and outcomes

Another advantage of such an approach is that it recognizes a number of truths about maternity patients:

- They are not “sick” or in need of treatment to be cured.

- They are the most likely among patients treated at hospitals to seek care as consumers.

- In many instances, maternity care may result in their first hospital stay.

How to apply value-based payments for maternity care

Value-based payment, although not new to maternity care, has not been widely adopted for this service line. Yet where payers and providers have experimented with value-based payment models in this area, they have achieved successful outcomes, as demonstrated in the case examples described below.

The case examples involve the use of blended case rates and bundled payments, respectively.

Under both models, the provider receives a single payment reflecting preset spending targets informed by the provider’s average historical expenses. The provider carries most of the financial risk and can realize shared savings if it remains under these targets or can incur a loss if it exceeds them. The key difference between the models is the number of maternity care episode components.

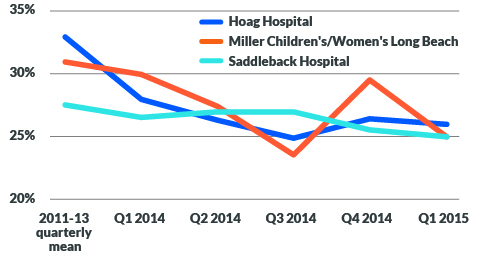

Case example: Blended labor delivery rate. In 2014, hoping to demonstrate that removing any financial incentive from performing a C-section would increase vaginal deliveries, the California Health Care Foundation launched a program in which physicians and hospitals received a single case-rate payment regardless of delivery method.b A initiative’s primary goal was to reduce California’s C-section rate for low-risk mothers to under 23.9% by 2020. In just one year, the three participating hospitals reduced low-risk C-section rates by 20% (from 27%–33% to 19%–24%).

Graph of changes in C-section rates at each participating hospital

Source: Pacific Business Group on Health (2015), Case study: Maternity payment and care redesign pilot, October 2015.

The pilot program was a partnership among the hospitals and select health plan partners. The hospitals used the case rate for only 10% to 20% of their total births, yet the impact stretched to all deliveries at the hospitals. This pilot resulted in nearly $2 million in immediate savings for the three hospitals, assuming a conservative average savings estimate of $5,000 per averted C-section. These changes can also potentially lessen the number of future C-sections, representing $4 million in avoided costs for one year in the three hospitals.

Blended case rates provide savings large enough to make an impact, but they tackle only the delivery component of maternity care. The opportunity for greater savings lies during pregnancy, where a bundled payment can cover preventive actions that help avoid high-risk delivery and reduce the number of C-sections and associated expenses.

Case example: Maternity care bundled payment. Although published results from commercial maternity bundled payment programs are limited, there have been successful programs in Medicaid. The Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute collaborated with a Medicaid HMO in southeastern Texas, Community Health Choice, to launch a maternity care plus newborn bundled payment pilot program with two health systems.c Under the program’s bundle, the two participating health systems were reimbursed for three delineated components (pregnancy, delivery and newborn) based on their historical costs.

During the first year, the health systems completed 1,246 maternity care episodes. The bundled payments had the following components:

Pregnancy component:

- Based on average prenatal costs from each provider’s historical data

- Prorated based on when the mother actually starts receiving care (between months 2 and 5 of the pregnancy)

Delivery component:

- Blended case rate using historical vaginal and C-section data

- Accounted for a risk-factor profile for each patient, including demographics, comorbidities and type and severity of the care episode

Newborn component:

- Based on the average historical costs for newbornsd

Overall, the financial results differed between the two health systems (see the exhibit below). Although neither provider took overt steps to reduce its C-section rate, provider B achieved cost savings as a result of an enhanced focus on prenatal care (the pregnancy component), a shift from C-section to vaginal deliveries (the delivery component) and fewer complications for babies (the newborn component).

Budget results for the two health systems

|

Percentage over/under budget |

||

| Maternity care components | Health system A | Health system B |

| Pregnancy | -1% | 7% |

| Delivery | 13% | -7% |

| Newborn | 100% | -10% |

| Total | 34% | -4% |

Source: Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, NEJM Catalyst, © Massachuisetts Medical Society.

Value-based design for maternity care

The key elements of value-based design for a maternity care are the episode-of-care parameters, the accountable parties and the payment mechanism.

Episode parameters. The episode of care should focus solely on the mother and include all services, both professional and facility services, provided during nine months of pregnancy through postpartum.e The episode should encompass prenatal care (e.g., ultrasounds, obstetric checkups), the inpatient stay, clinicians’ fees during delivery (e.g., OB/GYN, anesthesia) and postpartum care (e.g., follow-up visits).

Maternity care episode roles and responsibilities

- Advanced practice providers

Conduct intake and provide maternal physical and intital education - Ultrasound and imaging technician, radiology

Confirm pregnancy, measure growth and evaluate for placental complications - OB/GYN or midwife

Lead care for patient and design customized care program and connections to specialists and support providers - Maternal fetal medicine

Consult on high-risk pregnancies - Specialist

Consult on specific conditions that develop during pregnancy (e.g., an endocrinologist for gestational diabetes) - Nurse educator

Provide the patient with education and resources through the pregnancy on nutrition, chronic conditions (diabetes, blood pressure) and breastfeeding support - Anesthesiology

Provide pain management during delivery - Doula or birth coach

Offer patient support, coaching and advocacy during delivery - Postpartum support

Provide pelvic floor therapy, pain management, wound care and infection control

Source: ECG Management Consultants, 2020

This model is best implemented with women who have a low-risk pregnancy, absent of risk factors that indicate either the pregnancy or labor would be atypical (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, breech positioning, high/low amniotic fluid levels). Because a pregnancy can go from low- to high-risk during the prenatal and labor periods, it may be difficult for providers and payers to identify upfront which women would qualify for the episode-of-care. Therefore, providers must develop adaptable care pathways designed for managing not only the low-risk pregnancies for which they are accountable but also the high-risk pregnancies that will ultimately be excluded from the risk arrangement.

Specific episode parameters, including inclusion/exclusion, would be negotiated between the provider and payer and should be based on acceptable industry standards. It is important that the episode be well understood by all participants and relatively straightforward to manage and adjudicate.

Accountable parties. To be effective, an episode-of-care model requires an accountable party responsible for developing, implementing and monitoring the care transformation. This party also holds risk, so if the program is successful, it receives a portion of the shared savings, and if not, it owes an amount to the payer. For a maternity episode, either the hospital or physician group can be the accountable party. Alternatively, the episode could be jointly owned, with a health system managing the program and contracting with physicians, sharing the risk and the savings. Such an approach could be favorable for situations that involve the use of OB hospitalists or laborists.

Payment mechanism. To limit incentives for providing unnecessary C-section deliveries, the episode-based payment should include blended facility and professional fee rates for births, whether they are vaginal or C-section. Payments should account for the following factors:

- Quality. The arrangement should include quality metrics that align with the episode of care and other strategic priorities to ensure patients are not negatively impacted by reduced services. If providers do not meet quality thresholds, a portion of payment may be withheld.

- Target price. The price should be determined based on the historical baseline period, with adjustments for regional spending and underutilized services, if necessary.

- Funds flow. The arrangement should start with a retrospective methodology (where all providers are paid on a fee-for-service basis with a retrospective reconciliation) and shift to a prospective methodology (where the risk-bearing entity is paid a lump sum and is responsible for paying downstream providers).

- Risk level. The arrangement should include enough upside and downside risk to motivate real engagement.

- Benefit design. Tiered or narrow networks should be created to encourage members to seek out providers that are using the bundles.

Assembling the pieces

Many commercial insurers (Aetna, Cigna, Humana, BCBS) offer obstetric practices upside-only bundled payment arrangements. They believe entering into arrangements with physicians, rather than hospitals, is the best way to control the costs of hospitalization.

But interested obstetric groups should act fast. As commercial insurer programs mature, there may be less opportunity to design the bundle, leaving obstetric groups with little power to negotiate terms. Also, if an obstetric group is already working on reducing C-section rates, the potential shared savings it receives may be limited if it enters an arrangement having completed much of the care transformation work.

Because commercial insurers tend to focus their maternity episode-of-care efforts on obstetric groups, the biggest opportunity for hospitals is in direct-to-employer (DTE) contracting arrangements. Large employers such as Walmart, Boeing and Lowe’s employ a center of excellence model to implement bundled payments. and will fly employees to select locations for elective procedures. Obviously, that approach would not work for a maternity episode of care. A hospital could target smaller employers that operate in a single location, however, to enter a DTE arrangement as a local preferred provider. Most successful DTE arrangements tend to be with municipalities (e.g., state government, a teachers’ union that works with a local health system).

Early adopters will lead the way

Maternity bundles are the right model for patients, consumers, providers, self-insured employers and payers. Over time, these models can help meet the nation’s huge need for reduced costs and improved maternal outcomes. The current COVID-19 pandemic and its devastating impact on both the healthcare system and our economy underscores the need to bring healthcare stakeholders together to pursue such innovations that improve affordability and quality.

Organizations interested in pursuing an episode-of-care model should start by assembling key stakeholders and mapping out an ideal patient pathway from pregnancy through postpartum. This exercise will help them analyze and articulate which services should be included in a bundle and illuminate gaps and barriers that may limit success.

Organizations also should perform preliminary analyses to ensure they can maintain sufficient margins under a bundled arrangement. Once an organization understands its current state, it should begin conversations with payers and employers to determine interest. Early adopters will have a strong advantage in maintaining market position and growing volumes in this increasingly competitive service line, where consumers can make well-informed decisions about where and how they will seek maternity care.

Footnotes

a. Chappell, B., “U.S. births fell to a 32-years low in 2018: CDC says birthrate is in record slump,” NPR, May 15, 2019.

b. California Health Care Foundation, “Reducing unnecessary C-sections in California,” July 10, 2018.

c. De Brantes, F., and Love, K., “A process for structuring bundled payments in maternity care,” NEJM Catalyst, Oct. 24, 2016.

d. Newborns with high-acuity conditions were excluded from the study because they would skew the average episode costs significantly.

e. Unlike many existing maternity episode-of-care programs, newborn care should not be included because (1) the mother and baby are separate patients cared for by distinct providers who have different focuses, and bundling them may have adverse outcomes; (2) the feasibility of bundling these services may be limited from a payment perspective, and patients with “normal newborn” DRGs can spend time in NICU, which would be logistically challenging to pay retrospectively; and (3) there is significant variation in these costs (NICU versus no NICU) and limited ability for providers to control for this variability. However, once the program is successful, newborn services could be added as a pilot program. The postpartum period can be customized according to provider and payer preference, and typically includes a visit at six to eight weeks postpartum.

Cost variations in maternity care

For self-insured employers and payers, maternal care can be particularly burdensome due to case-to-case cost to payer and patient variations. While “global payment” structures exist for the prenatal, delivery and postpartum period (typically six to eight weeks), costs associated with the delivery can vary widely depending on the type of delivery (vaginal versus C-section) and unexpected complications that tend to arise late in a pregnancy (gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, etc.). Even for women receiving excellent prenatal care, it is impossible to predict the eventual delivery method, and a C-section can cost two to three times as much as a vaginal delivery. Based on a 2013 study by Truven Health Analytics, the average cost of intrapartum for a C-section delivery is $24,572, while for a vaginal delivery, it is $16,165. This difference affects providers, too — a C-section adds a day in the hospital, which fills postpartum units and creates throughput challenges for busy L&D units.

Value-based care proposition for stakeholders in maternity care

- Self-insured employers/payers

Value-based care allows for more accurate budgeting for costs associated with maternity care, and it helps avoid surprise variation in benefit costs. - Clinical providers

Value-based care gives provider incentives to focus on comprehensive prenatal care that can reduce unnecessary complications. - Acute care facilities

Value-based care encourages partnering with clinician providers to see maternity care as a continuum, and it provides financial stability by reducing revenue variation. - Patients

Value-based care provides the ability to predict out-of-pocket costs, and it reduces unnecessary C-sections and other interventions, while improving maternity outcomes.

Structure of hospital and physician group episode-of-care models

Hospitals and physician groups are both potential accountable entities for bundled payment, but their stance toward such an approach differs.

Hospitals. Under a hospital-driven episode-of-care model, the hospital is the accountable entity as they typically have the resources to implement the multidisciplinary care transformation initiatives needed to manage a bundled payment. They are better positioned than physician groups to take on financial risk, making them a strong potential partner for bundled payment.

Physician groups. Under a physician-driven episode-of-care model, an obstetrics group is the accountable entity. Payers have an increasing preference to enter into agreements with physician groups because these groups determine utilization and direct patient care. However, not all physician groups have the resources needed to manage the patient, and some may rely on the hospital to provide these services. Physician groups therefore may not want to take on risk for actors outside of their control.