When Push Becomes Pull: The Next Phase of the Transition to Value

Despite cancelations of mandatory models, physician demand for advanced alternative payment models (APMs) will pull the transition to value forward.

Until recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) was aggressively pushing the transition to value forward with mandatory models. Despite a slowing of this activity with CMS’s cancelation of some mandatory episodes, evidence suggests the transition is likely to once more accelerate, driven by physician interest in APMs, which will grow as the economics of the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and Merit-based Incentive System (MIPS) become increasingly unattractive. Health systems will need to respond to physicians’ growing interest in APMs by developing sophisticated platforms to help their employed and aligned physicians succeed under a variety of these models.

Regulatory and Market Signals

As many are aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) recently canceled its three bundled payment Episode Payment Models (EPMs). The EPMs included two cardiac episodes (acute myocardial infarction [AMI] and coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]) and an orthopedic episode (surgical hip and femur fracture treatment [SHFFT]). a CMMI also modified its Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model to give “certain hospitals selected for participation in the CJR model [numbering 308] a one-time option to choose whether to continue their participation in the model.”

Some observers interpreted the cancelation of the EPM rule, along with changes reducing the number of physicians compelled to participate in the MIPS in the final 2018 Quality Payment Program (QPP) rule, as a “stall” in the transition to value in public programs. However, this interpretation ignores other market and regulatory signals and the financial pressures facing physician practices.

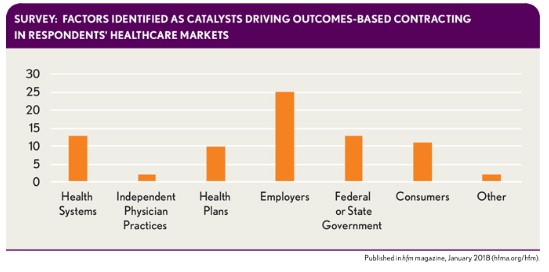

From a market perspective, it’s important to remember that Medicare isn’t the only payer that’s concerned about cost growth and sees opportunity to improve outcomes. Participants in HFMA’s October Thought Leadership Retreat identified employers as the most significant catalyst driving outcomes-based contracting in their markets.

In group discussions at the retreat, many health plan and health system executives commented that their state Medicaid plans (or their Medicaid managed care organizations) were aggressively experimenting with value-based contracts.

The regulatory signals from CMS come in a variety of forms.

First, in the EPM cancelation notice, CMMI indicated it was committed to voluntary PMs and referred to the much-anticipated announcement of the BPCI Advanced model.

Second, in mid-September, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) to help inform CMMI’s future efforts. It should come as no surprise that the Trump Administration would seek to align CMMI’s programs with the its philosophical ideas about the role of governmental intervention versus market mechanisms in health care. b The RFI sought feedback on steps CMMI could take “to promote patient-centered care and test market-driven reforms that empower beneficiaries as consumers, provide price transparency, increase choices and competition to drive quality, reduce costs, and improve outcomes.” In essence, CMMI is seeking suggestions for how to use market mechanisms to improve value. The RFI also indicates that CMMI will consider how new models it develops can complement existing models, suggesting a continued role for current programs in CMS’s and CMMI’s APM portfolio.

Third, CMS accepted a new round of applications for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) at the end of August. However, if the administration were truly interested in “stalling” CMS’s transition to APMs, it could have, instead, delayed or canceled the new application round, citing the relatively underwhelming results of the MSSP program to-date.

In fact, CMS recently released list of MSSP ACOs for 2018 includes 124 new participants. For various reasons, HFMA believes continued interest in the MSSP is due in part to the financial pressures facing physician practices.

Mounting Financial Pressure on Physician Practices

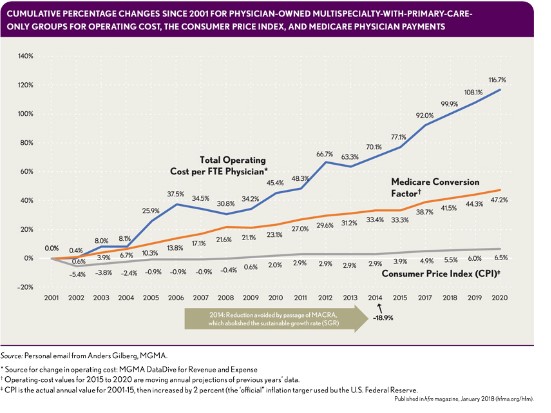

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) removed the threat of significant payment cuts to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, but it did not ensure the long-term viability of independent physician group practices. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) estimates that operating costs per-physician FTE have grown 92 percent since 2001 (see the exhibit below). By contrast, the Medicare conversion factor has increased by less than 5 percent. The fact that many health plans use the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule as the starting point for calculating negotiated rates with physician practices compounds the impact of this low growth rate. Although excluding a greater number of clinicians from the QPP due to low volumes of Medicare patients alleviates at least temporarily (for how long is unknown) some administrative burden related to participating in MIPS, this approach does not provide additional revenue opportunities to help offset ever-increasing expenses for practices of all sizes.

For small to mid-sized groups, the likely result is a continuation of the trend to seek alternatives to the traditional independent-practice model based on a fee for service. Practice alignment with (or employment by) health systems has steadily increased. Meanwhile, physician employment by health plans is increasing (as evidenced by Optum’s steady acquisition of practices, for example), and for physicians who want to remain independent, second-generation independent practice association models, such as Arlington, Va.,-Based Privia Health and Bethesda, Md.,-based Aledade, present viable alternatives to the health system employment/alignment model where available.

Physicians in small to mid-size practice settings seeking more sustainable arrangements will predicate their choices on a couple of factors. Key among them will be physician autonomy—the degree of physician/clinician engagement in decisions impacting their practice environment, perceptions about the practice’s ability to deliver high-quality care, and ability to succeed financially in the future.

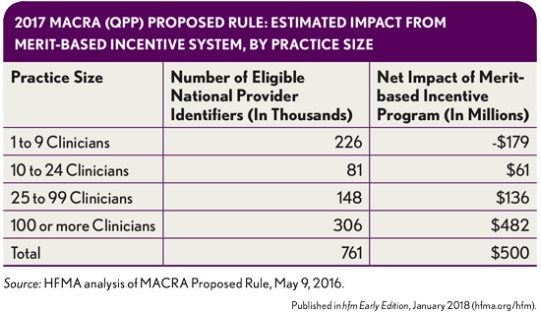

For larger practices, the MACRA/QPP 2017 proposed rule appeared to offer significant upside opportunity through MIPS. As shown in the exhibit below, practices with 100 or more clinicians were projected to see material MIPS bonus payments at the practice level.

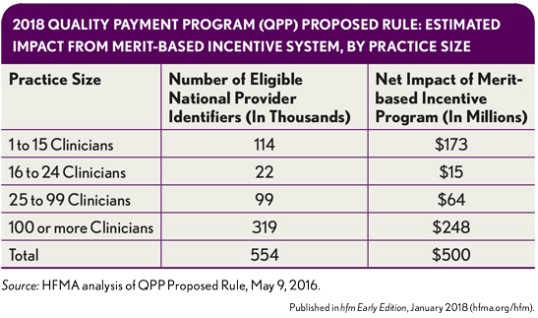

A considerable portion of the MIPs payments flowing to larger practices resulted from penalties that smaller practices incurred because they lacked the infrastructure to participate. However, as the following exhibit shows, expanded exclusions in the subsequent 2017 final rule and 2018 QPP proposed rule have reduced the MIPS bonus payments projected to flow to large practices by almost 50 percent.

The “hollowing out” of potential MIPS bonus payments will likely lead to more practices pursuing advanced APMs. Those that have not elected to do so to-date have been weighing opportunities in MIPS versus the downside risk they may face if they participated in an advanced APM.

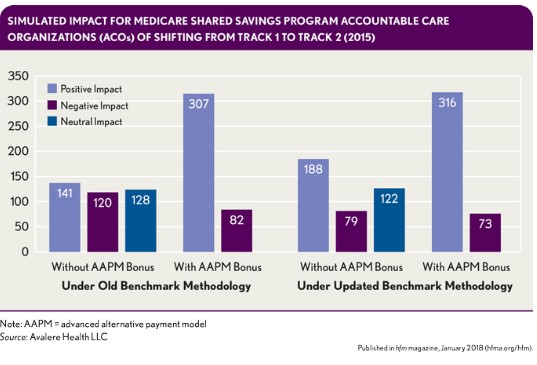

A recent analysis from Avalere Health in Washington, D.C., suggests that, for many organizations, the 5 percent advanced APM incentive payment outweighs the downside risk of participating in a qualifying advanced APM. As shown in the exhibit that follows, if all Track 1 MSSPs had been in Track 2 in 2015, the number of participating accountable care organizations (ACOs) experiencing a positive impact would have more than doubled under the old benchmarking methodology (for new MSSP ACOs) and increased by almost 70 percent under the updated benchmarking methodology.

Given these potential positive impacts, the expanded exclusions coupled with the 5 percent advanced APM incentive payment have likely altered the calculus for many physician practices and health systems, leading them to either apply for participation in the most recent round of the MSSP ACOs or actively consider their options moving forward.

At HFMA’s Thought Leadership Retreat, the CFO of a health system physician practice summed up the situation by stating: “I support the exclusions for smaller providers. However, it’s harder for my physicians to receive MIPS bonus payments. The remaining practices in the program are mostly larger, more sophisticated entities like mine. As a result, the business case for participating in the MSSP program now makes more sense than standing pat in MIPS.”

What Lies Ahead

CMS’s pause in aggressively mandating APMs does not constitute a wholesale movement away from these models. Rather, the transition to APMs will continue, being driven in large part by the stagnant Medicare payment environment, which will drive this change in different ways depending on practice size.

For smaller practices, the trend of physician employment by (or alignment with) larger entities is expected to continue. Physicians who seek employment will look for a health system that can successfully develop and execute risk-based contracts to maximize their bonus opportunities.

Meanwhile, aligned practices will want different things from a partner depending on the degree of alignment. The needs of closely aligned entities (i.e., participants in a clinically integrated network) will be more like those of employed physicians, because both will likely be participating in the same APM contracts. By contrast, loosely aligned practices (i.e,, participants in a second-generation IPA model) will look for high-quality, cost-efficient partners to which they can refer patients.

Despite the difference in choice of practice setting based on preference for autonomy, these practices have a common aim in seeking not only the scale necessary for economic viability in the current environment but also the sophisticated analytic and contracting capabilities necessary to help them thrive under risk-based payment models. As the remaining smaller, independent practices choose employers or partners, referral patterns within markets likely will change.

The same economic phenomena that drives smaller practices to seek employment or alignment with larger organizations will likely drive these larger organizations to participate in APMs. Beyond the financial opportunity (compared with remaining in MIPS) presented by the 5 percent incentive payment, larger health-system-based practices will need to participate in advanced APMs to provide bonus opportunities for employed physicians and funds flow for closely aligned practices, and to stimulate the development of an efficient care network to meet the needs of loosely aligned risk-bearing practices. Therefore, health systems (and their employed physicians) should continue building a “stable platform” from which to manage risk-bearing payment models.

Stable Platform Components

HFMA through its initial value project research identified the capabilities that comprise a stable platform. These capabilities derive from a focus on the following.

People and culture. To effectively participate in APMs, health systems require the ability to instill a culture of collaboration, creativity, and accountability across a network of providers. Compensation models and clinician education are key components of developing a high-value culture.

Often, compensation for employed physicians participating in risk-based models continues to be heavily influenced by productivity. c Health systems should consider moving, instead, to models that place a premium on reducing inappropriate utilization. Additionally, few organizations participating in risk-based models invest sufficient resources educating front-line clinicians about their value-based arrangements. d The relationship between ACO performance and physician awareness of participation in an APM has not yet been established. However, it’s reasonable to assume that increased levels of physician awareness and engagement related to participation in an APM are more likely to yield desired results compared to lower levels.

Business intelligence. Health systems participating in advanced APMs require the ability to collect, analyze, and connect accurate business intelligence comprising quality and financial data to support organizational decision making. Having this ability—encompassing data regarding both the organization’s internal performance and that of its network partners—facilitates a culture of accountability and continuous improvement. For example, a key to success in both episodic payment and shared savings/risk models is being able to identify and refer patients to high quality post-acute care settings. e

Performance improvement. To participate successfully in an advanced APM, a health system must be capable of using data to reduce variability in clinical processes and improve the delivery, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes of care. Boston-based Iora Health, for example, uses data gleaned from its electronic health record to identify high-risk patients through an internally developed scoring mechanism. The results then inform care teams’ morning huddles prior to patient office visits. More important, the process also identifies unscheduled patients who are at risk of ambulatory sensitive admissions and allows the care team to intervene. f

Contract and risk management. A sophisticated contracting function is required to fund and support integrated care networks. Such a function should be able to quickly model APM contracts from private payers (or proposed models from public payers). This capability can help a health system determine whether to participate in a public-payer advanced APM (including identifying which physicians should participate) or whether to negotiate key features of a commercial APM, such as patient attribution and risk adjustment, including determining which services should be included or excluded.

A Continuing Focus on Value

Under the Trump Administration, Medicare has reversed course and will not mandate APM participation for the foreseeable future. However, this change will not slow the transition to value. On the demand side, inadequate physician payment will drive smaller practices to seek out larger practice settings. Larger practices, in response to the same pressures facing smaller groups, will seek APMs for the additional revenue opportunities they provide. And despite CMS’s apparently having relinquished its role as “market steer,” value-based payment models will be available. On the supply side, employers and state governments will continue to push APMs in response to ever-increasing cost pressure.

Hospitals and health systems that misread CMS’s change in policy as a referendum on the transition to value risk losing market share as physicians seek employment or alignment with entities that can help them succeed under APMs. In this environment, hospitals and health systems will need to develop stable APM platforms by focusing on developing the core capabilities described here to make themselves attractive practice settings and partners for physicians.

Footnotes

a. CMS, “Medicare Program; Cancellation of Advancing Care Coordination Through Episode Payment and Cardiac Rehabilitation Incentive Payment Models; Changes to Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model: Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstances Policy for the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model,” Federal Register, Dec. 1, 2017.

b. CMS, “Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Innovation Center New Direction,” CMS.gov, page last updated on Dec. 1, 2017.

c. Ryan, A.M., Shortell, S.M., Ramsay, P.P., and Casalino, L.P., “Salary and Quality Compensation for Physician Practices Participating in Accountable Care Organizations,” Annals of Family Medicine, July/August 2015.

d. Schur, C.L., and Sutton, J.P., “Physicians in Medicare ACOs Offer Mixed Views of Model for Health Care Cost And Quality,” Health Affairs, April 2017.

e. Daly, R., “ACOs That Garner Shared Savings Increase,” HFMA Healthcare Business News, Aug. 30, 2017; and Mulvany, C., “BCPI Year Two Results: Findings and Implications,” hfm, November 2016.

f. Fernandopulle, R., “A Prescription for Primary Care,” Leadership, Nov. 4, 2014; and The Commonwealth Fund, “Transforming Care: Reporting on Health System Improvement,” Dec. 17, 2015.