Preparing for BPCI-A: Avoiding the Common Mistakes Providers Make when Implementing New Payment Models

This fall’s launch of the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced model presents a tremendous opportunity for provider organizations to move the nation’s healthcare system forward in its journey toward delivery of higher-value care.

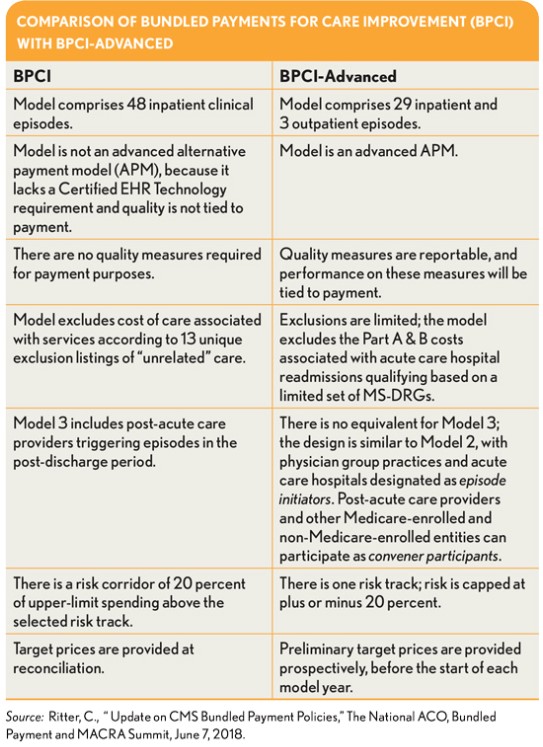

At the start of October, assuming the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) remained on course, the agency will have introduced the next alternative payment model (APM), Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI-A). This unveiling counts as one of the year’s biggest events in value-based payment.

Although some ambiguity has hovered over the value agenda over the past 18 months, with the leadership turnover at CMS, there is every reason to believe the agenda remains intact. Recall that the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) was passed with overwhelming bipartisan support. One can therefore reasonably conclude there is no lack of commitment on CMS’s part to test and scale new payment models.

Indeed, CMS has signaled that it is invested in helping hospitals and physicians succeed with BPCI-A: To demonstrate flexibility and collaboration, and to give providers extra time to prepare for the model, the agency recently extended some deadlines and reinstated a no-risk, or “shadow,” period similar to the one included under the original BPCI model (BPCI Classic).

Moreover, over the past nine months, and for the first time in several years, we have seen meaningful movement among commercial insurers in favor of risk-based contracts with providers, which is critical to accelerating the path to value. The unprecedented sharing of data that comes with BPCI-A will move the industry further along that path, enabling hospitals and physicians to embrace their new identity as high-value providers.

Signal Versus Noise

Much is yet to be learned regarding how BPCI-A will play out: Simply put, BPCI-A is an example of conceptualized rather than fully realized innovation. The purpose here, therefore, is not to spell out the program specifics. Rather, it is to provide insight and guidance regarding the approach organizations should take as they set out to participate in the program.

See related sidebar, “Bundled Episode ‘No-Go’ Zone,” below.

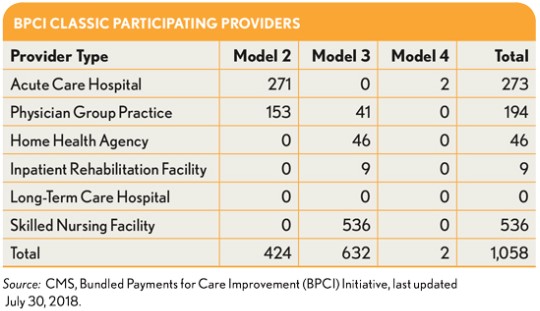

Providers have learned many lessons from prior tests of bundles over the past 10 years that can help them prepare for the new APM. It is important for hospitals and physicians to discern the signal from the noise when it comes to the current APM narrative. For example, although the evidence to support bundled payment as a viable approach continues to mount, most prior studies have been in the area of elective procedures, where hospitals and physicians knew sometimes six weeks ahead of time that they would be caring for a patient under a bundled payment model, which enabled these providers to take actions necessary to avoid risk. With BPCI Classic, the few times I was called in by an organization that was losing money, I didn’t even have to ask: I knew the organization had taken on clinical, operational, and actuarial risk that it was not prepared to manage.

There is a clear opportunity on the horizon for organizations that already are demonstrating a shift to deliver value-focused care to patients with chronic medical conditions. But what is most important for hospitals and physicians under BPCI-A is to begin with a focus on obtaining early wins and building cultural enthusiasm for a massive identity shift away from fee for service. Over the past two years, pure fee-for-service payments accounted for only 37.2 percent of provider payment, and that number is expected to drop to 25.4 percent by 2021. a

This trend suggests the efforts of providers that are leading the execution and scaling of APMs are well conceived and justified. Following are recommendations on how to succeed under APMs generally—and BPCI-A, in particular—based on experience gleaned from advising hundreds of organizations, many of which today are leaders in the field.

Achieve early success. Early success matters hugely, so the initial goal should be to keep it simple and win early. Looking at the organizations in BPCI Classic that dropped bundles, and at the nearly 25 percent of Pioneer accountable care organizations (ACOs) that dropped out of that program, it is apparent that much of that attrition was related to an overly ambitious strategy out of the gate. Physicians like to win, and a cycle of early failures—losing money, dropping out, regrouping—can kill morale, leading to provider fatigue. The problem is that many C-suite executives do not appreciate just how important it is culturally for physicians to see early success. Without it, an organization has little hope of getting to scale with value-based payment.

Another problem is that far too many healthcare organizations have embarked on bundled payment arrangements over the past few years where preliminary analysis would have clearly shown the arrangements would be money pits. Early experience suggests that physicians can tolerate maybe two quarters of losing money before they want to pull the plug, and hospitals can hold out for perhaps three or four quarters maximum. It bears repeating: Losing money with bundled payment kills morale among physicians and performance improvement teams.

Moreover, there simply is no reason to lose money with BPCI-A, and organizations can avoid this outcome by playing to their strengths out of the gate with the expressed goal of making money and sharing savings with those providers that helped create the savings. That is the foundation from which to build and scale a value strategy. This effort may begin with determining which episodes have adequate volume (100 episodes minimum) using the data provided by CMS. Then, the organization may evaluate current spending per episode against the CMS target price to determine how it performs financially relative to the target price, with the objective of identifying episodes where performance is below the target and then narrowing its focus to those conditions.

CMS also has allowed for a one-time no-risk retrospective review in March 2019, where providers can drop episodes that are not performing well economically, so provider organizations should take this opportunity to withdraw from episodes that are not winning at that time.

Master the competencies associated with becoming a high-value provider. One of the lessons we can take from BPCI Classic is that sepsis and pneumonia are difficult conditions to manage; many hospitals have lost money on those bundles. Clearly, that doesn’t mean provider organizations should give up and make no further effort to study and improve. Rather, this long-term goal should be clearly stated and championed from the start. What also matters the most for those new to APMs, however, is that physicians be set up to succeed from the start. The fact that a hospital or health system cannot become a high-value provider without physicians on board underscores the close interrelation between this recommendation and the previous one.

Set a pace for the BPCI-A launch that accounts for the organization’s circumstances. Healthcare organizations typically have ingrained in their cultures a desire to accommodate everyone’s needs and requests. They have difficulty knowing how to say no, and then they wonder why their implementations are suboptimal. As a result, each organization will face different challenges in launching BPCI-A because the implementation must occur in the context of the organization’s unique array of approved initiatives. Many organizations around the country do have one thing in common, however: Along with countless other initiatives, they are still deep into implementation of their electronic health records (EHRs).

Therefore, before undertaking a BPCI-A initiative, organizations should assess their operational readiness for competing on value, with the goal of identifying the perfect pace for proceeding under their unique situations (including taking stock of how the initiative will affect and interact with other initiatives). For example, a common bottleneck with care redesign efforts, which are necessary for success with BPCI-A, can be the schedules for installing EHRs. Organizations occasionally must make changes to an EHR, typically to reduce clinical and cost variation, and these changes must be prioritized.

Again, what matters most is to build positive momentum around the organization’s new identity as a high-value provider while sending the message that the organization honors its teams. The message is easily framed in the context of what employers and payers are willing to pay for. Setting the optimum pace promotes learning and ultimately will help ensure the organization can appropriately scale commercial, multipayer, and/or employer APMs.

Ensure sufficient resources are deployed for the initiative from the start. Among the most common mistakes healthcare organizations are prone to make when pursuing bundled payment models is under-resourcing the project, particularly in year one. Adding FTEs over the long-term should probably be avoided, but an investment for year one of BPCI-A should be made to cover the cost of analytics, care management, and physician leadership support. The effort going forward should yield more-than-adequate savings to cover these up-front costs. Investing insufficient resources at the start is tantamount to telling the team that the initiative and their efforts do not matter—a message that would likely yield mediocre results or worse. Organizations should find a reasonable balance, neither over-investing nor failing to invest adequately to ensure an effective launch. Common budget line items include project management support, analytics support, care navigators, care management, and physician leadership time.

Move from analysis to action. It is impossible to build, scale, and sustain high-value care without the requisite technology and tools to support such an undertaking. Telling a physician three months after the fact that his or her patient was readmitted is not helpful. CMS over the past three years has made public more data than it had over the previous 30 years.

The middle game—that is, once the bundled payment model is up and running—will require transparency at a provider level in as close to real time as possible. Unfortunately, however, the challenges for most organizations in providing such transparency are exacerbated by the fact that they have yet to realize the full potential of their EHRs.

Nonetheless, the data reporting need not be onerous. Out of the many possible measures to choose from, physicians will need to track only about 10 outcome-related measures to manage total cost of care in BPCI-A. Organizations could be tempted to choose as many as 100 measures, but it is counter-productive to track too much data because it contributes to data inaccuracy.

The measures should be selected by multidisciplinary, cross-setting teams, making sure at least one measure relates to patient experience. Process and quality measures are helpful to allow for root-cause analysis, but for day-to-day performance, outcome measures typically work best.

Healthcare organizations should share data at the provider level that can be used in practical analyses to illuminate major areas of cost and clinical variation. Experience has consistently shown that sharing the right data with physicians will cause immediate positive change and markedly reduce unnecessary cost and clinical variation. Specific measures that work to this end include total and variable cost per case, post-acute care cost per case, supply cost per case, pharmacy cost per case, average length-of-stay (LOS), skilled nursing LOS, and 30-day all-cause readmission. Providing these types of data compared with internal and external benchmarks often elicits immediate and sustainable change.

Be tomorrow’s leader today. All too often, healthcare organizations’ senior executives can be very excited for the first 90 days of a bundled payment initiative, only to then hand off the work to care teams and become disengaged. Being a high-value provider is something that everyone in the organization should own, and that ongoing spirit of ownership should reside with the executive team. Sustained executive support, encouragement, resources, appreciation, and development all go a long way in ensuring an organization’s success.

Healthcare organizations should take a lesson from the CEO from one of the nation’s leading integrated delivery systems, which launched a bundled payment initiative a few years ago. The CEO never missed a team call, never missed a meeting, was always positive, always asked great questions, and put her money where her mouth is. It’s no surprise that the bundles have been a huge financial win for her system, and that they have become a foundational payer strategy for her organization.

BCPI-A: A Major Step Toward Improving the Nation’s Healthcare System

The tremendous potential of the bundled payment became apparent to me 10 years ago as I was helping to ready my organization for the Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) demonstration. A dear friend and adviser suggested that my working as a lead for the ACE initiative would be the best work of my career, and although at the time I was skeptical, she proved to be right. When patients began to comment on our improved communication and coordination, when our already high clinical quality further improved, and when costs went down and our adherence to protocols went up, I knew we were on to something.

BPCI-A offers a great opportunity for hospitals, physicians, nurses, patients, and the community to reengineer the broken systems that have failed our nation for years and master the competencies of delivering high-value health care.

Bundled Episode “No-Go” Zone

In March 2019, provider organizations participating in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI-A) model will have a one-time chance to drop episodes in which they are losing money. For this month’s launch of the model, providers can be liberal in selecting episodes for participation because doing so allows them to obtain more data on their performance. The caveat is that being too liberal can be a distraction to the work at hand. If an organization elects to start broadly, it should make sure it clearly understands the care redesign interventions it will need to execute to ensure success.

Here are five recommendations of factors that constitute the “no-go” zone, where organizations should eschew participating in bundles.

Small populations. If an organization lacks a sufficient sample size to distribute the risk, everyone loses. To ensure an adequate level the actuarial risk, the population under consideration should not have fewer than 150 patients per year. And for a chronic disease, the number of cases may need to be higher.

Gaps in clinical performance. Given the retrospective nature of data, quality gaps in performance generally take 12 to 18 months to fix, whether the root cause is process- or outcome-related. Even if an organization has resolved high readmission rates for a population, the organization should not expect that payers will see the improvement until a year or more later. To address this problem, organizations should put their populations on evidence-based protocols and validate that the gaps in clinical performance quality have indeed been resolved—and only then take risk.

Low price point. Taking clinical and financial risk requires investments in care redesign, telehealth, care navigation, claims analysis and reporting, and more. But providing a better clinical outcome and a better cost outcome is not a race to the bottom. It requires moving beyond historical cost-shifting approaches and being willing to pay for and value the importance of gold-standard care redesign and care management. If insurers aren’t willing to pay for care management, then most chronic disease DRGs, for example, would likely involve too low a price point for a bundle and would be better managed in under a per-member-per-month approach.

Unnecessary actuarial risk. Most executives and clinicians believe that they can improve on their historical performance and perform better than their competitors. But if a provider is losing money on a population, its priority should be to focus on fixing that problem first. Organizations should make sure that they are establishing a favorable foundation at the outset to the extent possible. An organization always can scale up complexity if it has in place a foundation of success from which to build.

Lack of physician support. Healthcare payment reform is essentially care delivery reform. It matters less where a provider organization starts than that the start includes a strategy that physicians feel a part of and can lead. New payment models should be a means for provider organizations to further integrate clinically with their medical staffs. The work necessary to drive clinical redesign is real and substantial, and it requires physician leadership, enthusiasm, and engagement.

A healthcare provider organization cannot expect to succeed with risk that it is not clinically, operationally, actuarially, and culturally ready to tackle. The key is to follow the evidence and set physicians, staff, and patients up to win at the outset.

Footnote

a. LaPointe, J., “Value-Based Care Reduces Costs by 5.6%, Improves Care Quality,” Value-Based Care News, RevCycle Intelligence, June 19, 2018.