Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced: 5 Critical Issues

Many hospitals and health systems may benefit from participation in the Bundled Payments for Care Improvements Advanced program, but there are many points that organizations should address before pursuing this option.

When the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) created Bundled Payments for Care Improvements (BPCI), the benefits of participation were fairly straightforward. The program provided competitive and strategic advantages with limited initial risk.

The intricacies of BPCI-Advanced (BPCI-A) make decisions in pursuing this model a little more complex than the earlier version of BPCI. Here, we explore five scenarios as a basis for discussing the various critical issues that hospitals and health systems will encounter as they contemplate whether to pursue a BPCI-A option.

The exhibit below shows a reconciliation calculation for the baseline scenarios used throughout this article.

The Impact of the Benchmarking Methodology

To illustrate this point, let’s consider a scenario in which a health system that has previously succeeded in BPCI is considering participating in BPCI-A as a convener with its most successful hospitals and physician group practices.

First, however, we must consider some terms: CMMI defines a convener as “a type of Participant that brings together multiple downstream entities, referred to as ‘Episode Initiators (EIs).’” The convener’s role is to facilitate coordination among the EIs and to take on and apportion financial risk under the BPCI-A model. a CMMI contrasts a convener with a non-convener, describing that latter as “a Participant that is in itself an EI and does not bear risk on behalf of multiple downstream Episode Initiators.”

Analysis. It’s understandable that health system leadership might assume that participants that have successfully reduced costs and achieved savings will continue to be able to do so, yet that may not be the case. It is likely that they have already eliminated the easiest cost targets during the baseline period and may have a harder time squeezing out more savings. b

With BPCI-A, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also has implemented changes to the benchmark pricing methodology that incorporate both regional and historical pricing, rather than the strictly historical prices of BPCI. In addition, each hospital is assigned to a peer group based on the following criteria:

- Whether it is an academic medical center (AMC)

- Whether it is urban or rural

- Whether it is a safety-net facility

- Its census division

- Its bed size

Each hospital’s historical spending is adjusted for the patient case mix in each episode, and then for the peer-adjusted trend (PAT) factor, which both adjusts for differences among the peer groups (listed above) in spending for clinical episodes and projects each peer group’s spending for the clinical episode forward to the relevant year.

This methodology could mean that a hospital in a lower-cost rural setting might have a harder time meeting target prices in BPCI-A than it did in BPCI, because its benchmark will be adjusted downward by the low-cost position of its peers. Conversely, some participants that performed poorly in BPCI could do better in BPCI-A. A large, urban, AMC that is a low-cost provider relative to other AMCs in its peer group, for example, would benefit from the increased benchmark price set and might receive a positive net payment reconciliation amount (NPRA) without any other changes.

The health system in our opening scenario should analyze the remaining savings opportunities for all potential participating organizations and episodes rather than banking on past performance. The BPCI high-performers may still be attractive participants, especially if they have developed best practices that can be applied to new bundles, but the BPCI low-performers also could be valuable participants. Regardless of previous experience, it is essential to evaluate, in detail, the data and prospective target prices CMS makes available.

Use of a Convener Versus Internal Management

To illustrate this issue, let’s assume that a hospital that previously participated in BPCI through a convener has submitted two BPCI-A applications: one with a convener and one without. Now it needs to decide which path to pursue, if any.

Analysis. Conveners can offer a range of services from case management and protocols, to data analysis, to facilitating relationships with downstream partners. The convener often will share financial risk with the organization, fronting operating costs and sharing the upside or downside of the NPRA on the back end.

In deciding whether to pursue BPCI-A with a convener or on its own, a hospital or health system must determine how it will obtain the key capabilities required to succeed. For example, a participant that wants either to develop its own care management capability or to integrate BPCI-A with an existing care management function may prefer to participate independently. Similarly, if a participant does not obtain data analytics from a convener, it may use internal data analytic capabilities, or contract with a data analytics vendor that does not take a share of the NPRA.

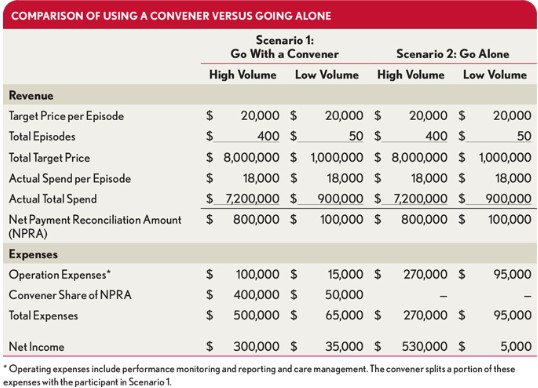

The exhibit below illustrates the potential impact of using or not using a convener, assuming performance is the same in both situations.

A hospital that is pursuing BPCI-A without a convener must invest in a performance monitoring system, fund staff for care management efforts, and oversee performance improvement initiatives. As the analysis shows, such a hospital may need high volume in its targeted bundles to offset these investments and operating costs.

Working with a convener changes the nature of the hospital’s costs for BPCI-A and can reduce the potential upside for the hospital by requiring that the NPRA be split with the convener. On the other hand, working with the convener protects the hospital from a portion of downside risk. Results will vary considerably depending on the contract terms and estimated results.

Hospitals with positive performance may lose net income if the convener is taking a set percentage of NPRA, whereas going it alone could have a better effect on the bottom line. Financially speaking, using a convener is more likely to make sense for a hospital if volume is low and the hospital has limited experience with value-based payment and managing risk.

Both of the scenarios shown in the above exhibit assume the hospital has the necessary electronic health record (EHR) infrastructure in place, because the program requires participating organizations to have Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT). c

The Role of Physician Group Practices

Here, to provide a basis for discussion, we will consider the case of a hospital that was an early entrant to the original BPCI program, and whose leadership now is excited to pursue BPCI-A arrangements. The hospital is in a very competitive market with large physician group practices nearby, some of which the hospital has worked with on bundled payment arrangements in the past.

Analysis. Before jumping into BPCI-A, this hospital should consider how its participation in the new program will be affected if the nearby physician group practices pursue BPCI-A.

CMS is giving physicians precedence in attribution of episodes in BPCI-A. Where physician group practices are participating, hospitals will be precluded from realizing savings for bundles targeted by the practices. But that decision by physicians does not obviate a hospital’s need to pay attention to BPCI-A.

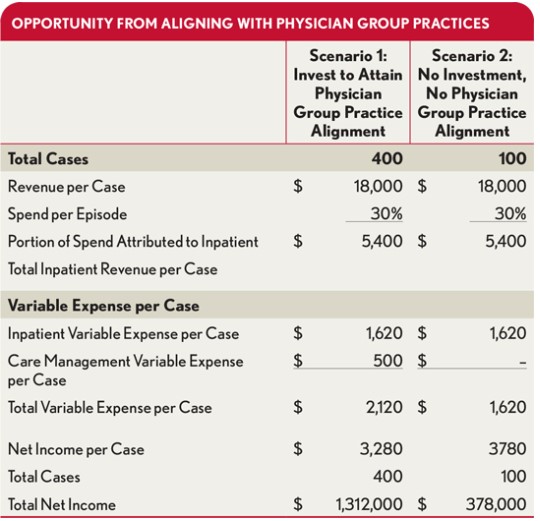

Physician group practices may choose to shift their episodes to hospitals that will best support them to succeed under BPCI-A through better care management and a focus on value across the episode. The group practices will find it difficult to “price shop” directly in BPCI-A because their own spending targets are adjusted in relation to the spending efficiency and case mix of the hospital to which their patients are admitted. However, if physician groups also contract with other payers for commercial and Medicare Advantage cases, they may more actively consider the price differences among hospitals when deciding where to treat patients.

Hospitals should open dialogue with physician group practices in their markets to understand which episodes (if any) the practices will pursue for BPCI-A or with commercial payers. Hospitals may choose to invest in making themselves attractive sites for the physician groups, offering superior care management. Although this approach would decrease the hospitals’ contribution margin per case, it could help them maintain or grow volume, as shown in the exhibit below.

Physician Opportunity to Qualify for MACRA Advanced APMs under BPCI-A

In this instance, let’s assume that a physician group practice is interested in BPCI-A because the participating physicians have an opportunity to qualify as part of an advanced alternative payment model (APM) under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). If the physicians qualify, they would avoid the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and receive a 5 percent bonus on top of Medicare Physician Fee Schedule payments.

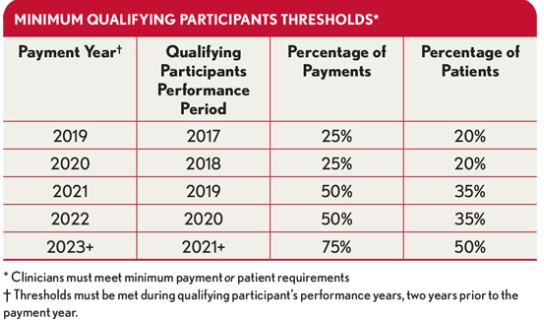

Analysis. To avoid MIPS and receive bonus payments, physicians must not only participate in an advanced APM, they must also be qualifying participants (QPs), which requires meeting strict CMS volume or payment thresholds. To be considered a QP in 2019, a provider must have at least 25 percent of payments be through Medicare or have 20 percent of Medicare patients covered under an advanced APM. d

These aggressive thresholds must be met during the QP performance period, two years prior to the actual payment year. In other words, to receive the QP benefits in 2021, these thresholds must be met in 2019. Compounding the problem, the volume and payment thresholds increase dramatically to 75 percent and 50 percent by 2023, as shown in the exhibit below. MACRA rules have their own complexities and exceptions and could also change.

To further complicate things, CMS has stipulated that, for convener participants that have both hospitals and physician group practices as episode initiators, QP determinations will be made at the level of the full group, meaning all eligible clinicians will be assessed as one group that either qualifies or not. It’s essential for hospital or health system leadership to understand these rules if obtaining the 5 percent bonus is a key motivation for participation in BPCI-A.

It is equally vital for hospitals to review the expected volume and revenue for their employed physicians (in detail if not participating through a convener) before assuming CMS will offer them an advanced APM bonus.

Interactions with Other Value-Based Payment Models

To illustrate this issue, let’s assume a hospital that operates a Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACO is interested in joining BPCI-A on the basis of having developed a robust population health management platform.

Analysis. With so many value-based payment programs coming from CMS, it’s essential to consider the interactions between different models when making decisions about BPCI-A.

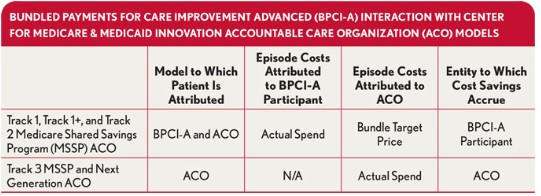

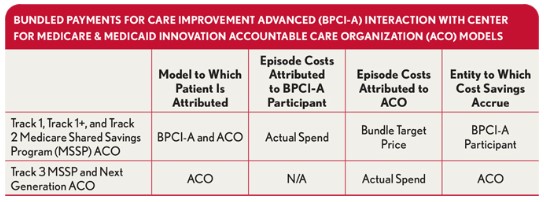

Patients can be attributed to multiple models simultaneously—but the impact differs by circumstance. For example, if a patient is attributed to an ACO, but is admitted to a hospital participating in BPCI-A for a relevant clinical episode, this patient would seem to be in both models. CMS’s rules to eliminate “double dipping” have various interpretations depending on the ACO model and/or track (see the exhibit below left).

A BPCI-A participant will not be accountable for any cases for which the beneficiary is in a Next Generation or MSSP Track 3 ACO. If a high portion of the Medicare patients treated by the hospital are attributed to one of these categories of ACOs, there may not be enough volume to offset the investments required for BPCI-A.

The complexity of the interactions between BPCI-A participation and an ACO could produce some unexpected results. ACOs in MSSP track 1, 1+, or 2 that also are pursuing bundled payments could lose both savings and volume.When CMS calculates the shared savings for ACOs in these tracks, the spending for the ACO patient’s episode will be set to the target price, regardless of actual spend, thereby removing the opportunity for the ACO to achieve savings on these episodes.

In a true nightmare scenario, these forgone savings could make the difference between exceeding the ACO Minimum Savings Rate threshold and failing to do so. However, if the ACO’s spend on the bundle is greater than the BPCI-A target price, then applying that target could help the ACO achieve savings. ACOs in track 1, 1+, or 2 also should be aware that physician group practices participating in BPCI-A may “scoop” their patients and accrue any savings. This potentiality may motivate some ACOs to convert to Track 3.

Our hospital with an MSSP ACO should consider which party has the greater incentive to manage the episode, and reevaluate its value-based payment agreements from there.

Careful Deliberation Required

At press time for this article, CMS was scheduled to release historical spend data and target prices in May. Given the new benchmarking methodology, and the considerations discussed above, hospitals and health systems should perform intensive data analysis of each bundle to determine whether they likely can achieve savings through an existing or to-be-built care management program.

If a hospital or health system can identify bundles in which savings are likely, it should consider the issues raised here, which could make or break the decision. How will BPCI-A fit into the hospital’s or health system’s overall value-based payer strategy?

Next, the organization’s leaders should consider interactions with other current value-based payment models at the organization and how those interactions are likely to play out over the next few years. Participation in BPCI-A may be an opportunity to strengthen physician relationships, but it could also undermine physician alignment.

Ultimately, it is imperative that hospitals remain aware of any modifications in the BPCI-A regulations. The details are important and may have a significant impact on performance. And they are likely to change.

Footnotes

a. CMS.gov, “BPCI Advanced” (innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced), page last update April 30, 2018.

b. CMS uses a baseline period of Jan. 1, 2013–Dec. 31, 2016, to calculate historical spend portion of benchmark price.

c. All hospitals must use CEHRT and at least 50 percent of the eligible clinicians in each physician group practice must use CEHRT.

d. CMS has also developed ‘Partial QP’ thresholds; when met, the clinician can opt out of MIPS, but does not qualify for the AAPM bonus.