3 essentials for creating and managing a high-value PAC Network

Health systems participating in risk-based payment models need a well-developed and well-executed post-acute care (PAC) strategy to succeed.

Reducing spending on post-acute care (PAC) is a primary goal for any health system’s PAC network strategy. Discharging patients to the appropriate PAC setting and a high-value provider within that setting is imperative to both improve outcomes and reduce the total cost of care for all their patients.[1] Although organizations may take different approaches, interviews with leading health systems suggest effective strategies share a common focus on three elements:

- Use of quantitative and qualitative data to differentiate performance

- Provider engagement built on a compelling value proposition for PAC providers

- Infrastructure that supports bidirectional feedback loops in support of care redesign

1. Access to data for network development and care redesign

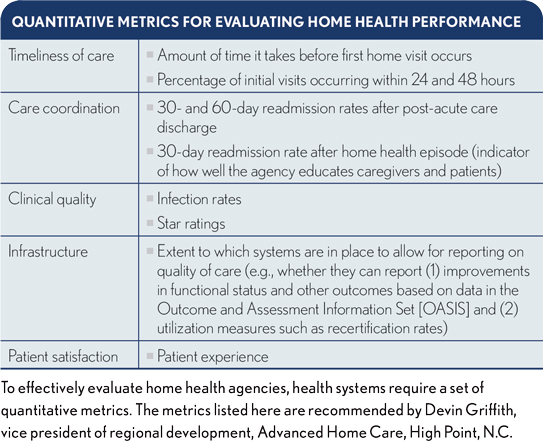

Not surprisingly, many health systems use quantitative data to manage their networks and identify participants. The data typically includes episode costs, Medicare star ratings for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other indicators of care delivery quality and efficiency.

Quantitative data can help health systems clearly differentiate high-value and low-value providers. But this data is not helpful for understanding the performance of providers in the middle of the pack. Publicly available data for PAC providers also tends to be dated and often does not provide a complete picture of an organization’s current performance and capabilities, particularly where a provider has recently experienced management turnover.

Given these limitations of quantitative data, health systems also should access qualitative data for assessing potential PAC provider partners (see also the sidebar).

Gary Whittington, CFO of Lovelace Health System in Albuquerque, N.M., says, “Without the qualitative data and human interaction, you could have a SNF or HHA [home health agency] that has changed management, completely redesigned care and significantly improved its quality. And if all you rely on is the quantitative data, you’ll miss a good partner.”

2. A highly engaged PAC provider network

Not surprisingly, the more SNF and HHA competitors there are in a market, the easier it is to build a high-value PAC network. This situation favors urban markets, which tend to be more competitive.

Yet high-value networks can be created in rural markets. For example, in a rural market where one health system refers to three SNFs with different owners, the potential loss of referrals is a strong incentive for each SNF to focus on improving performance to continue being part of the network.

Given the burden of participating — including the need for analytic resources to provide data to the health system sponsoring the PAC network and the administrative time commitment for meetings — the primary incentive for PAC providers is increased volume with an adequate payer mix. This incentive is particularly important for SNF providers as care migrates increasingly to outpatient settings and more Medicare inpatients are discharged directly to home. Health system and potential PAC provider participants should be transparent about their specific goals for the network to avoid misunderstanding.

“Post-acute providers will want to know three things,” says Devin Griffith, vice president of regional development, Advanced Home Care, High Point, N.C. “First, how committed is the health system to the network? Second, how large is the network, and how many referrals does it believe will be shifted into the network from other providers? And finally, what are the long-term goals for the network that might increase the number of lives under management and, therefore, subsequent referrals?”

Health systems can expect PAC providers participating in the network to re-evaluate their participation at least annually to ensure that their goals are being met relative to the resource investments required to participate.

Case examples. Lovelace Health System and LifePoint Health, based in Brentwood, Tenn., are two health systems operating in competitive markets that have used different approaches to develop their high-value networks.

Lovelace narrowed its network from the outset, which is the more common approach. Under this model, the health system communicates to both in-network and out-of-network PAC providers that preferred status for network participants is predicated on their performance relative to others in the market. This approach gives PAC providers incentives to pursue continuous quality improvement efforts to either remain engaged within the network

or become a participant.

LifePoint initially invited all PAC providers in the market to participate. Although not all agreed to do so, those that did are included in the high-value network regardless of their initial quality and cost data. The health system has communicated to the participating PAC providers that, for the time being, they will remain preferred providers as long as they are engaged in the network (participating in data review meetings and making progress on quality improvement goals, for example). However, over the longer term, the health system may narrow the network. The decision to narrow, if necessary, will be based on a provider’s improvement relative to historical performance and its improvement relative to other SNFs in the market.

Like all things, starting with a broad PAC network presents pros and cons. The obvious disadvantage is the health system is not starting with an initial group of high-value providers. The health system therefore risks leaving possible NPRA [net payment reconciliation amount] on the table, particularly in models such as the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, where the regional cost factor becomes a greater portion of the provider benchmark.

Nonetheless, LifePoint believed it was important to give all its community partners a fair opportunity to participate in the network. For example, LifePoint’s approach gives a management team that has recently taken over a SNF an opportunity to improve performance and avoid being penalized for historical practices.

The approach also helps mitigate internal cultural issues. For example, community hospitalists occasionally “moonlight” as medical directors for PAC providers. Excluding a PAC provider from the network without giving it an opportunity to address performance-improvement issues can create alignment challenges with physicians who wear multiple hats in the community.

PAC providers in less competitive markets also have a compelling reason to collaborate with health systems interested in reducing PAC spend. Through collaboration, PAC providers can obtain access to benchmarks, best practices and insights that can help them improve their margins in the face of the shift to value-based payment models.For example, participating in networks can help a SNF not only reduce readmission rates (and potential related penalties for excess readmissions) but also manage more complex patients and succeed under the Patient-Driven Payment Model when it is implemented in federal fiscal year 2020.

3. Robust infrastructure to support PAC redesign

As HFMA has identified through its Value Project research (hfma.org/industry-initiatives/the-value-project.html), performance improvement doesn’t happen by accident. Reducing the total cost of care and improving patient outcomes requires infrastructure and IT systems. Each health system and its PAC partners will have unique performance opportunities, which will be revealed through ongoing analysis of data, as described in the previously cited first part of this two-article series, published in the July 2019 issue of hfm. And acting on these opportunities requires strong relationships and bidirectional communication supported by investments in appropriate infrastructure.

To support these interactions, LifePoint is providing its hospitals and physicians with toolkits to support PAC network engagement and the care redesign process. The kits include:

- Standard slides for administrators to present to PAC providers

- Script-like talking points to support those presentations

- PAC-specific performance dashboards

with comparisons to setting averages for distribution - Comprehensive episodic performance data from baseline and performance periods

- Attendance log templates for PAC meetings

- Archived presentation materials and content, including recordings when appropriate

Chris Frost, MD, national medical director of hospital-based providers for LifePoint, says the goals are to uncover:

- PAC-provider pain points with LifePoint’s discharge and other care-coordination processes

- Thoroughly understand each PAC provider’s capabilities

- Encourage provider-to-provider communications

Each item in the toolkits is designed to reinforce bidirectional conversations between the health system’s and PAC provider’s care teams.

The feedback LifePoint has received from its PAC partners through this process has resulted in a more robust care plan and exchange of information to support the patient’s transition of care.

Frost offers the example of how the health system is redesigning its traditional discharge summary to include key pieces of information that gives the PAC providers more insight into the LifePoint care team’s recommended next steps for the patient. Frost notes that specific information added to the discharge documentation include:

- Any medication changes, the rationale for those changes and any clinical monitoring required to assess the efficacy of the changes

- Follow-up items that cannot be left outstanding (e.g., outstanding pathology report on a lung biopsy)

- Follow up with new specialists not previously involved in the patient’s care plan before the inpatient stay

- The patient’s short- and long-term goals of care (e.g., return to a functional status that allows the patient to be the primary caregiver to an ailing family member)

The PAC network partners also stress the importance of receiving the information when a patient arrives, which creates an expectation for hospitalists to ensure patients do not leave the facility without a comprehensive discharge planning summary. Regulatory and accreditation agencies may allow for a significant gap to occur between the patient’s discharge and completion of the discharge summary. This gap can obviate the clinical benefits that can be obtained from real-time clinician-to-clinician communication.

To accommodate the new timing demands, hospitalists are provided with a voice recognition tool for dictating the summaries.

Other requirements for information exchange also come with increasing integration between a hospital and its PAC partners. For example, while developing a high-value network, one hospital learned the pharmacy in a high-value SNF partner wasn’t open during evenings. Although the hospital always tried to minimize after-hours discharges to SNFs, on those few occasions when it had to send a patient to this SNF after hours, it also needed to provide a day’s supply of the patient’s medication. This insight resulted from bidirectional conversations with the SNF partner.

Effective bidirectional communication improves quality in other ways. Creating a high-value network provides the added benefit of building new relationships between the caregivers. Health systems report that before they established effective channels of communication, their unit nurses and hospitalists had little to no contact with the clinical staff at their partner PAC providers. Now, with communication processes in place, if SNF staff have a question about a patient, they call the nursing unit from which the patient was discharged for clarification.

In fact, it has become a national trend for hospitalists to deliver care in both the hospital and the SNFs, an approach that can facilitate improved communication and coordination between the acute and post-acute settings. The new approach has helped avoid unnecessary emergency department visits and readmissions.

A strategic imperative driven by the shift to a value focus

Health systems that cannot effectively manage PAC spend will struggle to succeed in Medicare risk-bearing alternative payment models. They not only will fail to achieve a positive financial outcome, but also will miss the more important opportunity to significantly improve patient outcomes.

Progressive health systems, however, such as those interviewed for this article, have developed strategies and tactics that address the core prerequisites necessary to discharge patients to the appropriate PAC setting and collaborate with preferred PAC providers to improve care delivery.

Although each health system’s strategy will be unique, based on the organization’s individual circumstances with different specific action steps, all health systems will need to focus their high-value PAC network strategies on gleaning data for evaluating potential PAC partners, engaging in-network providers and providing the infrastructure needed to establish effective channels of communication

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following individuals for their generous contributions of time and insights that were instrumental in developing this series.

- Chris Frost, MD, national medical director of hospital-based providers, LifePoint Health

- Devin Griffith, vice president of regional development, Advanced Home Care

- Craig Tolbert, principal, DHG Healthcare

- Gary Whittington, CFO, Lovelace Health System

- Michael Wolford, senior manager, DHG Healthcare

[1] See the first part of this two-part series on executing a PAC strategy, “Why PAC discharge choices are key to success under risk-based payments,” in the July 2019 issue of hfm.