Optimizing Care Delivery Through Perioperative Value-Based Care

Improvements in perioperative care can result in improved hospital margins and better patient care.

Striking the balance between minimizing cost and maximizing output is a challenge that most hospital systems are facing in the pursuit of value-based healthcare delivery and procurement. Further, to minimize cost of care, care providers must know which types of care are the most efficient and effective. This space is one where physician leadership can and should play a highly important role to educate and support various other members of the leadership team.

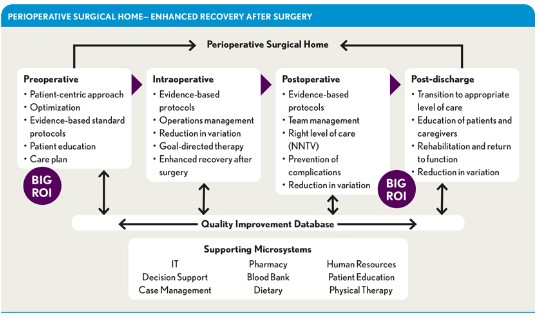

A hospital’s perioperative care process is quite complex, involving multiple subprocesses, healthcare professionals, and systems in support of surgical care. Perioperative care generally refers to the four phases of surgery: preoperative (including optimization of underlying diseases and “pre-habilitation”), intraoperative, postoperative, and post-discharge. The perioperative process often is the primary source of hospital admissions, driving hospital margins (i.e., accounting for 55 to 65 percent of margins) and having the greatest impact on total hospital supply costs, which are variable. a Hospital programs focused on improving care coordination and quality throughout the perioperative process can succeed only if they consider the complexity of the health system and of individual surgeon and patient preferences and understand the dependencies, predictable delays, and potential resource constraints.

The goal of value-based care delivery is to improve clinical and patient experience outcomes while holding the line on costs. This seemingly simple approach is becoming the most effective means for measuring care delivery, and it aligns all stakeholders around a common viewpoint about what it means to deliver high-quality, cost-effective care in the perioperative setting.

The What and Why

The literature surrounding value-based care delivery and payment is mixed regarding the direct impact of this approach on improving health, containing costs over the long term, and achieving key quality objectives across the U.S. healthcare system. b There is no question that patients who undergo surgical procedures are receiving highly innovative and technologically advanced perioperative care. But 46 to 65 percent of all adverse events in hospitals are related to surgery—especially complex procedures. c

Using the perioperative-value based care (P-VBC) approach can help providers achieve better outcomes. Despite the considerable hype around the transition from volume to value, there remains very limited understanding of how to drive the paradigm shift in a clinical care setting. Most of the challenges originate from differences in perspectives. Executive and administrative colleagues are highly motivated to implement this approach, but clinicians are more ambivalent because they are not sure what changes can be made beyond reducing costs.

To be successful, P-VBS efforts must have a comprehensive and cohesive approach that includes financial, operational, and clinical inputs. A successful P-VBC model includes all stakeholders and components across the surgical episode. Moreover, it is critical that physicians play a leadership role in determining how best to deliver value throughout the perioperative care process. Indeed, physicians have a unique understanding of both the clinical needs of their patients and the operational needs of the healthcare organization. Organic changes that are driven by physician leadership and other stakeholders in the organization are much more likely to be hard-wired and become standard of care as compared with changes that are driven by outside consultants.

The How

A cohesive approach to P-VBC should be defined around a specific patient’s planned surgical procedure. Consider the example of a patient undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) across the following perioperative phases: preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative, and post-discharge. Care delivery models such as the perioperative surgical home and enhanced recovery after surgery include many of these components, and their effectiveness is supported by data published in the literature.

Preoperative. Once the patient and the surgeon have agreed on the need for surgery, a crucial next step is for them to agree on what is a successful outcome. Some patients want to return to play golf while others will be happy to simply walk without a cane. Physician leaders can take the lead in educating their colleagues on the need for such conversations.

Once the physician and patient have reached a consensus on the outcome of the surgery, the work can begin on optimizing the patient for surgery by addressing underlying diseases, deploying pre-habilitation activities, and completing a risk assessment.

Conceptually, a patient can be cleared for surgery but not optimized for surgery. For example, a patient can undergo surgery with mild anemia and be administered a blood transfusion in the operating room, which can be associated with a longer length of stay, higher costs, and higher readmissions rates. This patient is “cleared for surgery.” On the other side, a similar patient’s surgery can be postponed and the anemia be treated before the patient undergoes the surgical procedure. This patient is “optimized for surgery.” Ensuring that chronic disease conditions and other clinical characteristics such as diabetes and hypertension are optimized (i.e., the patient receives all of care for these conditions that is appropriate and they are in the best possible condition) can have a positive effect on postoperative complications, length of stay and readmission rates, and ultimately costs.

Pre-habilitation processes such as home physical therapy, smoking cessation, diet optimization, and exercise can have a profound impact on postoperative clinical and economic outcomes. Identifying the appropriate resources and deploying them in advance of the procedure is a critical step that often is overlooked.

By identifying and stratifying patient risks during the preoperative phase, providers can best tailor the deployment of resources during the operative and postoperative phases to ensure that the procedure results in the best possible outcomes. Tools to determine high-risk patients exist but are underutilized, creating an approach that treats every patient the same and leaves gaps in care that could result in less-than-ideal outcomes for some.

Intraoperative. During this phase (on the day of surgery), a clinical pathway is required to facilitate a decrease in care delivery variability. The clinical pathway should include the perspective and input not only of the facility perspective but also of the physician. Physician leadership is particularly important in the development of the clinical pathways, as such leaders can serve as the liaison for ensuring physician input and perspective is appropriated solicited and incorporated into the pathway design. For example, very few facilities have clinical pathways that are directed toward integration of anesthesia and surgical care, such as the use of regional anesthesia and goal-directed therapy. The organization’s unique aspects should be considered, including cultural, clinical, operational, and financial needs.

Postoperative. As indicated previously, a significant number of costly complications can occur during the perioperative period. In a world where each postoperative complication is associated with a decreased profit margin for hospitals—from an average of 5.8 percent in patients without complications to an average of 0.1 percent for patients with complications—any complication should be avoided. d

The care at this postoperative stage typically is segmented, often resulting in a lack of clear accountability. Consider the following: Intraoperatively, each patient receives care from a large team of physicians, nurses, and other providers. Yet following surgery, there is no clear “team”; rather, the patient received care from isolated pockets of nurses, hospitalists, and surgeons (who are not always in house). Moreover, most clinical pathways are highly generalized when it comes to the postoperative clinical care, resulting in significant clinical variability.

Considering this lack of structure, it should be no surprise that most perioperative complications occur in the postoperative period. Creating a team and establishing and executing specific care coordination protocols will markedly enhance outcomes during this phase of care.

Post-discharge. Currently, when a patient goes from the hospital into the post-discharge phase of care, there tend to be wide gaps in communication between sites of care. The best way to close these gaps is to create an official guideline for hand-offs between the hospital team and the community team. Specifically, the hospital team should communicate directly with the patient’s primary care team providing details about the procedure the patient underwent, any complications that might have occurred, and the plan and expectations for recovery. This step also will significantly enhance the process of medication reconciliation.

An Optimized Model for Surgical Care

A P-VBC model that incorporates the improvements described here will integrate clinical, operational, and financial elements to drive a higher-value, patient-focused episode of care. The perioperative surgical home provides a conceptual framework for realizing these improvements and has been widely implemented by healthcare organizations with financial success. For example, implementation of this model at UC Irvine Health has correlated with cost savings to the organization surpassing $3 million in the area of joint replacement and spine surgery. Patient experience scores also have improved during the implementation. e

A lack of coordinated care has been a key driver of health system inefficiency. Lack of uniform systems and processes, fragmented and uncoordinated care delivery, lack of continuity of care, and even a “more is better” philosophy all contribute to health system inefficiency. An acceptable healthcare delivery system should enable patients to obtain healthcare services and deliver services cost-effectively according to established quality standards. In short, the P-VBC model provides a system view for affecting change and improving care delivery and coordination for patients in their surgical journey.

Footnotes

a. Ryan, J., Doster, B., Daily, S., and Lewis, C., “ Key Performance Indicators Across the Perioperative Process: Holistic Opportunities for Improvement via Business Process Management,” ScholarSpace, Jan. 4, 2017.

b. Porter, M.E., and Teisberg, E.O., Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results, Boston, Mass., Harvard Business School Press, 2006; Zywiel, M.G., Liu, T.C., and Bozic, K.J., “ Value-based Healthcare: The Challenge of Identifying and Addressing Low-Value Interventions,” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, May 2017.

c. Zeeshan, M.F., Dembe, A.E., Seiber, E.E., and Lu, B, “Incidence of Adverse Events in an Integrated U.S. Healthcare System: A Retrospective Observational Study of 82,784 Surgical Hospitalizations,”Patient Safety in Surgery, 2014.

d. Stuhlberg, J.J., and Bilimoria, K.Y., “ Complications, Costs, and Financial Incentives for Quality,” JAMA Surgery, September 2016.

e. Raphael, D.R., Cannesson, M., Schwarzkopf, R., Garson, L.M., et al, Total Joint Perioperative Surgical Home: An Observational Financial Review, Perioperative Medicine, 2014; Garson, L., Schwarzkopf, R., Vakharia. S., et al., Implementation of a Total Joint Replacement-Focused Perioperative Surgical Home: A Management Case Report, Anesth Analg 2014.