10 Steps Toward Health Equity

A report from HFMA's 15th annual Thought Leadership Retreat.

The push to achieve equity in health and healthcare is daunting. It’s a multifaceted societal quest in which the goal is to fix disparities that have been entrenched throughout U.S. history.

HFMA’s 2022 Thought Leadership Retreat brought together stakeholders from across healthcare Sept. 15-16 in Washington, D.C., to advance the dialogue in this effort. Although far-reaching strategies and policies remain works in progress, it’s clear that leaders of provider organizations and health plans can generate positive momentum to improve health equity.

One takeaway from the event was that the complexity of the challenge can’t be a reason to avoid addressing it. With a recent report from Deloitte putting the cost of health inequities at $320 billion today and a projected $1 trillion in 2040, the U.S. healthcare system will not produce anything close to optimal population health until it addresses the gaps.

“It’s not just the economic costs that are a concern,” said HFMA President and CEO Joseph J. Fifer, FHFMA, CPA. “There’s a moral imperative. There are quality-of-life issues.”

Even amid a slew of potentially overwhelming financial and operational challenges that are facing healthcare organizations, the industry’s recent emphasis on striving to achieve health equity must be sustained.

“When the financial pressures are huge, what do organizations do? They many times get really focused on the here and now. Not [on] something where the seeds need to be planted and play out over time,” Fifer said.

“And so one of our challenges is: While all these kinds of [equity initiatives] are in place and happening, will they have staying power?”

A statement from the British epidemiologist Sir Michael Marmot rings true, Fifer added: “Health inequities and the social determinants of health are not a footnote to the determinants of health. They are the main issue.”

Framing the challenge and the path forward was the focus of the retreat, which was sponsored by AKASA, FORVIS, GHX, Humana, ShiftMed and Strata Decision Technology. As presented in this report, the event fostered rich discussion around ways to approach a problem that isn’t as intractable as it may seem.

1. Define the stakes

Healthy People 2030, a federal government initiative, defines health equity as “the attainment of the highest level of health for all people.” Health disparities are differences linked with social, economic or environmental disadvantages. Such differences impede health equity.

“For the purposes of measurement, health equity means reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and its determinants that adversely affect excluded or marginalized groups,” said Stephen Thomas, PhD, professor of health policy and management and director of the Center for Health Equity at the University of Maryland.

William A. McDade, MD, PhD, the first chief diversity and inclusion officer for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), invoked the term excess mortality to describe the implications of disparities. Society should view disparities as deficiencies in healthcare quality, he said.

One point of clarification is that achieving health equity doesn’t mean everyone receives the same treatment.

Equality should not be the goal because “this idea that if we treat everybody the same, we’re treating everybody fairly is based on a wrong assumption,” said G. Rumay Alexander, EdD, RN, FAAN, professor in the School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We like different things, we have different desires.

2. Work on your organization’s culture

Much of the effort to foster health equity comes down to a mindset of cultural humility and “human empathy,” Alexander said.

Those who interact with patients should strive to hold “multiple perspectives without judgment,” she added. “It’s the judgments that get us in trouble — ‘Superior, inferior. Better than, less than. Higher than, lower than. More deserving, less deserving.’ It’s the way we size up a situation, but it sometimes is in the way we actually do resource allocation.”

To promote an environment in which those with diverse perspectives are empowered to voice those perspectives in service of health equity, leaders must make clear “that you are respecting the fact that we are different,” Alexander said. “It’s going to make you a better decision-maker, a better provider and a more productive and effective organization collectively.

As an example of an organizational approach, Intermountain Healthcare tries to go beyond diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) to focus on “belonging,” said Russ Elbel, assistant vice president for Medicaid for SelectHealth, the insurance arm of the Salt Lake City-based health system.

“Part of that is making sure your workforce is representative of the people you serve and that you’ve addressed underrepresentation, and that people feel comfortable,” he said.

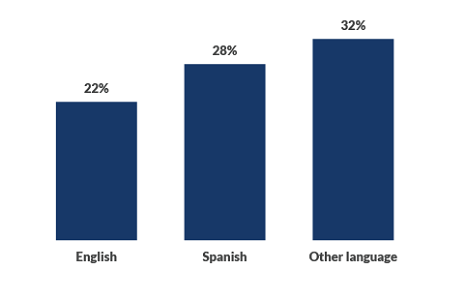

Intermountain Healthcare: C-section rate by language

This data shows disparities in C-section rates among the health system’s patient population. The organization is aiming to be more proactive about connecting patients with interpreter services.

3. Set your strategy

Healthcare organizations are taking steps to ensure health equity is central to their strategic planning.

In 2020, for example, Intermountain added equity to a list of seven other “fundamentals of extraordinary care” (among the others are safety, quality and patient experience).

“These fundamentals are used to help with strategic planning every year and deployment of goals for the organization,” Elbel said. “Equity being in that same playing field has helped to start to accelerate the work for the organization as a whole.”

Bellin Health, based in Green Bay, Wisconsin, has a multidisciplinary health equity steering team consisting of primary care clinicians, interpreters, case managers, population health managers, and representatives from human resources and other areas.

Initiatives to address inequity can raise uncomfortable questions about issues such as racism, which is why such programs need to be backed by leadership. Being open to criticism also is crucial, said Jim Dietsche, CPA, executive vice president, accountable care services, and CFO for Bellin Health.

“If you’ve never asked questions like that or never taught things like that, you’re going to get feedback,” he said. “Most of it was very constructive to start building awareness.

4. Assess your workforce

To the degree that health equity hinges on establishing a more diverse workforce, the education and training of healthcare professionals become key steps.

“People tend to seek care within their own communities, and they don’t have a sense of trust and go outside their community for care,” said McDade of the ACGME. “By giving racially concordant care, you improve access to care for individuals who would rather forgo care than receive care in an environment that dehumanizes them, discriminates against them or fails to communicate effectively with them.”

A 2018 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that Black patients were more likely to talk extensively about their health problems if they were seeing a Black physician compared with a white physician, McDade noted. And the impact on key process and outcome metrics was significant. Most notably, the authors found that the racial gap in cardiovascular mortality for men could be reduced by 19%.

The problem is that not enough minorities enter the physician ranks. For example, McDade shared data showing that the share of Black physicians was stagnant between 2004-05 and 2018-19.

Thus, policies should go beyond paving the way for minorities to succeed in their education and residency. Policymakers also should strive to improve the care provided by white and Asian physicians to underserved communities.

“If those individuals aren’t focused on trying to serve the underserved, we’re using a lot of medical school seats for people who aren’t going to change health disparities,” McDade said.

5. Participate in new payment models

With many hospitals and health systems struggling to muster the resources needed for day-to-day operations, participating in payment models that can offer the needed funding to support health equity may seem all the more intimidating.

The federal government hopes to help. CMS and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) have made equity a cornerstone of their long-term strategic plan under the Biden administration, said Dora Hughes, MD, PhD, chief medical officer for CMMI.

“One of our very first lessons was that [CMMI] in our first 10 years had not focused enough on disparities or equity,” Hughes said. “We also did not focus on Medicaid or low-income populations.”

CMMI is seeking to partner more extensively with Medicaid on innovative models that cover a wider variety of patient demographics. But the providers serving those populations often are the ones that would struggle in value-based payment (VBP) models, especially in scenarios where downside risk could further strain already-thin margins.

CMMI plans to offer more support to providers that may previously have been left out of participation in VBP, starting with assistance during what can be an overwhelming application process.

“Whether it’s a benchmark adjustment, whether it’s upfront funding, and certainly there’s been a lot of discussion about social risk adjustment — all these different types of financial arrangements are on our radar, and we will be testing them out,” Hughes said.

6. Know what to measure

Organizations are making progress at capturing the caliber of data that can provide a roadmap to reducing disparities and improving health equity.

For example, Bellin Health added 74 selections to its race, ethnicity and language fields to identify nationalities such as Somali and Hmong, along with individual Native American tribes. It also aims to capture information on sexual orientation and gender identity, including preferred pronouns.

All clinical teams can see the information in an app that breaks down a metric such as blood pressure control based on rural vs. urban areas and, within each of those, advantaged vs. underserved segments.

“If you want to truly do population health, you have to have this information,” Dietsche said. “It’s eye-opening to providers.”

In its VBP models, CMMI is looking to incorporate data that’s more granular in assessing equity measures, Hughes said. And the recently published United States Core Data for Interoperability version 3 allows for the capture of enhanced data on demographic categories such as sexual orientation and gender identity.

Takeaways from attendees

Small-group discussions involving attendees, whose roles span administrative and clinical leadership positions with providers and health plans, are an annual staple of HFMA’s Thought Leadership Retreat. Here’s a sampling of the insights that came out of the discussions on the push to achieve health equity.

On current efforts: Organizations are working to develop the type of leadership structure and governance that can help them address the root causes of inequity. Diversity in board membership and creation of executive positions that have oversight of diversity, equity and inclusion are among the key steps being taken. As one attendee said, the task of improving health equity is “not something else we do. It’s what we do.”

On current challenges: Among impediments to achieving health equity, attendees cited funding deficits in a fee-for-service payment system, language barriers, lack of trust, challenges with health literacy and an absence of cultural humility. “We are not doing a good job of asking communities what they need,” one attendee said. “We are telling them what they need.”

On the need for better data: Disparities in data sources are a challenge. Sources that can be better leveraged include ZIP codes and community health needs assessments, although assessments need to be approached in the right way and not as a means to find new revenue opportunities. In addition, qualitative data can be gathered by conducting listening tours in the community.

On making the business case for health equity: “It’s the foundation of what we do, but it’s not the foundation of how we get funded,” one attendee said. Federal initiatives and value-based payment models can create momentum to move in a positive direction. Even when the finances of an equity initiative work, however, depicting that on a balance sheet can be difficult.

On partnerships: Collaboration with community organizations is vital to advance efforts to address the social determinants of health and improve health equity. Among many other options, attendees said partnerships can be struck with faith-based organizations; schools; organizations that help with food, housing or transportation; organizations that offer behavioral health intervention; and youth organizations such as the YMCA and YWCA.

7. Take a holistic view

Organizations increasingly recognize that health disparities largely stem from the social determinants of health (SDoH), meaning issues that extend well beyond the walls of a hospital or clinic. Seeing the big picture is vital to help all patients attain optimal health.

“We know the problem, but what’s driving the problem? It’s the social context of health disparities [that] we need a better understanding of,” said Thomas of the University of Maryland.

He added, “You can’t just take a brochure off a shelf of the American Cancer Society and say, ‘Let’s put this in Spanish, and [we’ll assume] this reaches the Latinx community.’ You actually need to empathize with that community. You need to know their history. That takes time.”

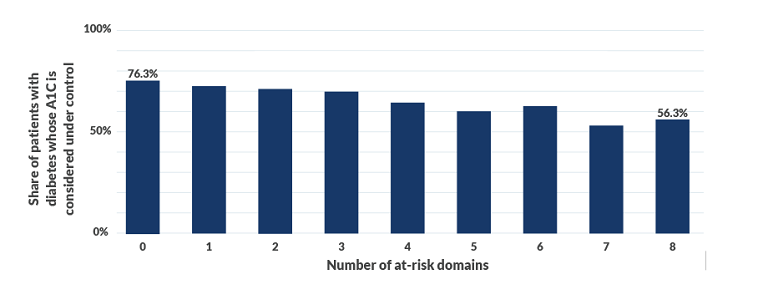

Bellin Health’s director of population health recently gave an internal presentation that showed an association between the number of at-risk SDoH factors and A1C control rates for patients with diabetes, Dietsche said (see the exhibit below). Such insights didn’t come as a surprise, but a deeper dive established that the three biggest factors were transportation, food insecurity and financial resource strain.

“None of those are really physical [risk factors],” Dietsche said. “We changed our processes after we learned that.”

The health system serves a diffuse geographical market, and people in outlying areas may not have the same type of access as those who live in or around a city center. A nuanced view of patients thus may be needed geographically as well as demographically.

“The issues related to social determinants of health in one part of our region are dramatically different than in another,” Dietsche said.

Bellin Health: The link between SDoH and A1C control

This data shows the association between the number of social determinants of health (SDoH) domains at risk and a key outcome measure for patients with diabetes.

8. Look to the community

The effort to address SDoH factors that drive health disparities is virtually impossible for providers to tackle alone.

“We need to know the difference between medical care and public health,” said Thomas. “And for my medical care people [in attendance], I need you to be better advocates for public health. You see the mess we can get in if we don’t: We’ll overrun your hospitals with people who don’t need to be there.”

He described a program at the University of Maryland that leverages community relationships to improve preventive care in local neighborhoods. Through the program, Black-owned barbershops and salons become “trusted information centers” for vaccinations and screenings.

Barbers and stylists first were trained to speak with customers about colonoscopies. The same approach was incorporated when the pandemic hit, with training focusing on how to guide customers from vaccine hesitancy to vaccine confidence.

More recently, the program coordinated screening for peripheral artery disease in a barbershop.

“We thought it would take two or three months to get 100 people screened,” Thomas said. “[It happened in] one day.”

“I didn’t have to change their worldview,” he added. “I didn’t have to change their political party. They were treated with dignity and respect.”

In 2021, the Biden administration called and asked Thomas about the feasibility of scaling the initiative. That led to the launch of Shots at the Shop, a nationwide network of 1,000 barbershops and salons.

9. Make the business case

Forward-thinking financial leadership is vital because “you cannot do this on the cheap,” UNC’s Alexander said. “It is going to take time, money and people. It cannot sit outside as an addition to the strategic plan. It is the overlay of the strategic plan and everything you do.”

In a panel discussion, HFMA National Chair Aaron Crane, FHFMA, MHA, asked how hospital and health system leaders can ensure they get buy-in and support from their boards and fellow executives for initiatives to improve health equity.

Elbel of SelectHealth responded that for health plans, participation these days in government programs such as Medicaid managed care generally requires being able to identify and address disparities.

“Every government program as a purchaser is asking for your outcomes and your processes,” he said, “and have you integrated those processes in your organization to really address disparities?”

Dietsche said assessments of ROI can’t be piecemeal.

“Our focus is not on top-line revenue [from an initiative],” he said. “It’s on bottom-line performance. We know bottom-line performance comes if you align lives because you’re going to manage the care better. The patient’s outcome is going to be better; their experience is going to be better. The connections to all the different care aspects are going to be better.”

As to whether an ROI is needed as part of health equity initiatives, HFMA’s Fifer said that without one, “We’re swimming upstream in this country. Let’s just face facts. It behooves us in the industry to think creatively about how to create a financial return on investment.”

10. Be innovative and agile

Northwell Holdings, a for-profit subsidiary of Long Island-based Northwell Health, partnered this year to launch a platform that seeks to develop breakthrough AI solutions with which to close health equity gaps.

One of the key criteria in developing products was feedback from clinicians, said Richard Mulry, president and CEO of Northwell Holdings.

“We’re not trying to be a tech company that develops a solution and then tests it behind a health system firewall,” Mulry said. “We’re trying to take that idea with the physicians and the nurses — the people who are caring directly for the patients whose outcomes are quite variable despite our best efforts to track them with care navigation.”

To establish an environment where innovation can thrive, Mulry said, organizations need to encourage stakeholders to submit ideas without fear of failure.

They also need to define the problem they’re trying to solve and avoid trying to “boil the ocean.” And joining a consortium of likeminded organizations can allow execution to happen faster and at scale.

In terms of commitment, organizations need to realize that the task of achieving health equity is sweeping and not anything that will be achieved through a five-year plan, Alexander told attendees.

“Things are changing too fast,” she said. “Every six months, you’re going to need to do a deep analysis, paying attention to the social, technological, economic, environmental and political climate so that you can make adjustments.”

She encouraged leaders to “pay attention to who’s having the babies in your communities, because that’s who’s going to be in your workforce and market.”

“We’re going to be dealing with this for quite some time,” she added. “Getting ourselves ready to do it — regardless of race or color or creed or gender or sexuality or generation or body size — is the work of us all.”