10 Keys to Restoring Trust in Healthcare

A report from HFMA's 2023 Fall Thought Leadership Retreat

The issue of restoring consumer trust in the U.S. healthcare system encompasses a wide range of concerns. Factors in the perceived loss of trust include anxiety and confusion over costs, entrenched inequity, a glut of misinformation about vaccines and other treatments, and data and privacy breaches.

To examine the problem and explore solutions, HFMA’s 16th annual Thought Leadership Retreat convened leaders from across the industry Sept. 28-29 in Washington, D.C. The genesis of the event was a report in HFMA’s “Healthcare 2030” series that described the ebb in trust and linked the issue to deteriorating population health outcomes.

Macro industry trends make the prospects for engendering trust seem discouraging. Healthcare is “more costly, more complicated, more unaffordable, less humanistic,” Zeev Neuwirth, MD, an author and longtime physician executive, said during the retreat.

Consumers aren’t the only ones who see flaws in the system. Greater numbers of frontline clinicians are questioning whether they have the resources and structural support to make the difference they envisioned.

“Does the cost support the outcome?” asked Tim Porter-O’Grady, DM, a nurse leader and senior partner for health systems with TPOG Associates, LLC, citing rankings that show the United States performs poorly on many measures of health and healthcare. “We’re clearly not getting what we’re paying for, but what are we paying for? What is the purpose of the delivery system?”

Effecting change in the system to produce a more definitive answer to that question would go a long way toward enhancing consumer trust. But that’s a daunting challenge.

“Healthcare is a complicated system, so therefore trust and the opportunity to rebuild or restore [it] — that solution has to be systemic,” said C. Ann Jordan, JD, president and CEO of HFMA. “It’s going to require everyone in this room.”

The retreat represented a step forward, she noted.

“These discussions that we’re having, that requires trust in and of itself,” Jordan said. “We have to be able to include everyone.”

As described below, the key takeaways from the retreat can serve as a roadmap to enhance consumer confidence and clinician faith in the U.S. healthcare system.

Thank you to our sponsors and partners

HFMA appreciates the generous support provided by the sponsors of our Thought Leadership Retreat: Humana, Ensemble Health Partners, Equity Quotient, Guidehouse, Turquoise Health and Wells Fargo.

We also extend our appreciation to the American Association for Physician Leadership and the American Organization for Nursing Leadership for their partnership in hosting this event.

1. Defining the issue

One key to solving the apparent trust deficit in healthcare is to precisely understand the goal.

“It’s not so much that our job is to restore trust. Our job is to make ourselves trustworthy,” Neuwirth said, referring to a directive described in the 2000 book The Trusted Advisor.

“We can’t create trust,” added Neuwirth, who this year authored his own book, Beyond the Walls: MegaTrends, Movements and Market Disruptors Transforming American Healthcare. “That’s a relational issue that requires two people. But we can make ourselves trustworthy.”

Healthcare stakeholders may be misled by surveys that consistently show nurses and physicians at the top of the most trusted professions. But those results don’t speak to consumers’ experiences with the industry overall.

“We trust [clinicians] in many ways more than we trust the systems that they are a part of,” said Bruce Levy, MD, associate chief medical informatics officer for education and research with Geisinger. “And I think it’s a reflection of how our healthcare systems have evolved from that Marcus Welby sort of a picture into these incredibly complicated, almost Byzantine systems that have been created around healthcare.”

The issue goes to the heart of the healthcare mission.

“People who don’t trust the healthcare system, they just don’t seek care, and there’s going to be higher rates of nonadherence,” said Alexander Ding, MD, MBA, associate vice president for physician strategy and medical affairs with Humana. “People are going to end up being sicker, and it’s going to cost the country a whole lot more in terms of healthcare costs when they have to come in at a much more urgent stage later on.”

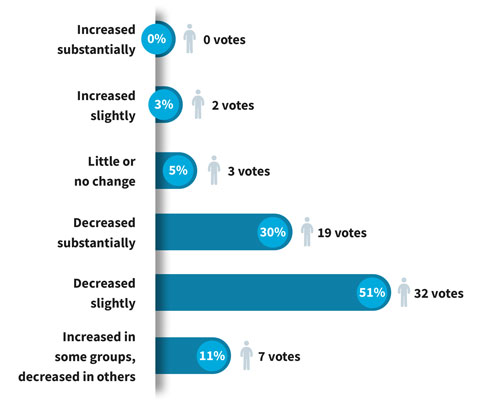

Stakeholder feedback: How has patient trust in healthcare changed since 2020?

2. Measuring trust

Finance leaders and other healthcare stakeholders should strive to rigorously assess the trust their patients and customers have in their organizations.

Neuwirth referred to a formula known as the Trust Equation, which was described in The Trusted Advisor and includes four variables:

(Credibility + Reliability + Intimacy) / Self-Orientation

Neuwirth singled out the intimacy factor, explaining, “Emotionally, do I connect with you? Do I feel safe? Do I feel I can share with you?”

Self-orientation, the denominator, should be deemphasized as part of a trusting professional relationship.

“You can have all the confidence and intimacy and reliability you want, but if I believe that you are in this for yourself and you’re not in it for me, that completely demolishes trust,” Neuwirth said.

There also should be an emphasis on going straight to the source for information on your customers’ trust levels.

Neuwirth noted that in 2016, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented a short survey to gauge trust. Initially, results showed nearly half of veterans did not trust the VA as a source of healthcare. The department followed up with qualitative interviews to pinpoint areas for improvement.

More recently, the survey showed nearly 80% of veterans trusted the healthcare they received from the VA.

3. Boosting affordability

A prerequisite for improving trust in the system is making care more affordable for patients and ensuring they have access to needed therapies.

“Under many surveys and assessments, the U.S. [healthcare system] is objectively ranked as the leader in novel scientific innovation, whether it’s through technology companies, new devices, new drugs, etc.,” said Carter Dredge, lead futurist with SSM Health. “But where we fall short as an industry is in affordability and access and equity types of things.”

During a discussion with Dennis Dahlen, FHFMA, MBA, CPA, HFMA’s National Chair and CFO of Mayo Clinic, Dredge described his role as an architect of a model designed to make healthcare more affordable and accessible on a large scale. As seen in Civica Rx, the not-for-profit generic-drug company that launched in 2018 and now counts more than 55 health systems as members, the model can be thought of as a healthcare utility.

The model incites what Dredge called intentional commoditization — in this case, the commoditization of generic drugs that have been on the market for years and are not likely to undergo modification.

“Instead of taking a ton of shots on goal — one player placing a lot of bets — I would view intentional commoditization at the product level as the exact inverse,” Dredge said.

“It’s everyone pooling their demand together to agree to [a] purchase — to commit to a strategy that [says] we think the desire for uniformity and access for patients trumps the need for pseudo differentiation,” Dredge added.

The consumer-facing impact is significant, he noted: “We dramatically improve the [likelihood] for patients that when their physician says this is the appropriate therapeutic, they get it.”

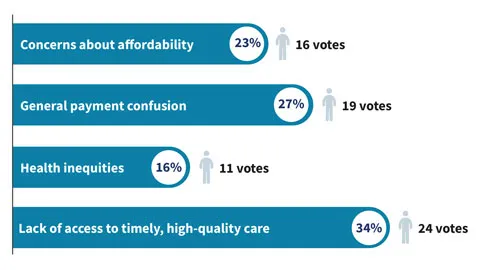

Stakeholder feedback: Which of the following has the most negative impact on patient trust in the U.S. healthcare system?

4. Increasing value

Even though most patients aren’t aware of the concept of value-based care in technical terms, they appreciate any steps taken by providers to put their whole-person health front and center.

“More than ever, we absolutely need value-based care to build a person-centered health system,” said Purva Rawal, PhD, chief strategy officer with the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). “Our fee-for-service [FFS] payment systems are not designed to meet the needs of patients in a holistic way.”

CMMI works to establish a value-focused infrastructure through mechanisms such as upfront investments in data and other resources for participants, regulatory flexibilities, care coordination tools, and primary care payment stability and predictability, Rawal said. The goal, as set out in a strategic blueprint issued in 2021, is for all FFS Medicare beneficiaries to be in an accountable care relationship by 2030.

“This means that we’re really focused on models that can facilitate longitudinal relationships between providers and patients,” Rawal said. “I think of this as making sure patients have a provider that is quarterbacking their care across settings and across other providers to make sure that their needs are being met — not only their medical needs, but also their health-related social needs.”

CMMI’s Accountable Health Communities Model, a five-year initiative that ended in 2022, sought to address the social determinants of health (SDoH) by bridging the gap between clinical care and community services. Rawal said takeaways highlighted a substantial consumer demand for services that can address SDoH.

The shift to value-based payment is not happening quickly enough among legacy stakeholders, Neuwirth said, especially compared with retailers and disruptors such as Humana and Optum.

“The finance and the business model is the key, and it’s actually the keystone that’s going to hold the arc of the future of healthcare,” he said. “If there is an area of expertise that’s going to be able to transform healthcare, it is within the financial and the business-model realm.”

Ding said Humana has almost 70% of its provider contracts in value-based payment arrangements, with metrics showing superior outcomes via preventive care, better disease control among patients with chronic illness, lower costs and higher patient satisfaction.

5. Healing the clinicians

Healthcare organizations can’t optimally serve consumers without clinicians who are fully engaged. That state is increasingly difficult to achieve amid levels of stress and strain that were a problem before the pandemic and have been exacerbated since.

The term burnout doesn’t capture what’s going on in many cases, Neuwirth said.

“It’s not really burnout,” he said. “It’s actually moral injury.”

The concept of moral injury has roots in the military, Neuwirth noted, and “it means that, ‘I’ve actually been participating in something or allowing something to happen that goes against my morals.’” He referred to “an epidemic of depression, demoralization, moral injury that’s happening in healthcare.”

Porter-O’Grady said engaged nurses have unique opportunities to connect with patients in a way that increases trust in the healthcare system.

“We manage the healthcare journey,” Porter-O’Grady said. “We manage the patient’s experience, we manage the patient’s movement throughout the system. We live with the patient, we experience with the patient, we resonate with the patient, we suffer with the patient.”

Thus, for C-suites, a key to improving the system is to involve nurse leadership more directly.

“Do you have people like me sitting at your strategic table so that I can raise the questions that invariably and ultimately will impact your ability to succeed? Because I may not be designing [strategy], but by God, I’ll be implementing, and if I don’t implement it, it’s not going to happen,” Porter-O’Grady said.

6. Improving transparency

The opacity of the healthcare system discourages consumer trust. Stakeholders should be looking at ways to make prices and other key information more transparent and digestible.

Much of the most substantial work is taking place on the health plan side, since insurers have the ability to aggregate price information from across a market.

Health plan price transparency files are making progress as accessible tools, said Danielle Lloyd, senior vice president for private market innovations and quality initiatives with AHIP (formerly America’s Health Insurance Plans). In commercial plans, 50% of enrollees now have the credentials they need to access price-listing apps. Only 10% are using them, however, according to surveys.

Physicians may be in the dark about pricing structures as much as patients are.

“We don’t understand the financial mechanisms,” said Stephanie Duggan, MD, regional president and CEO of Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital in Saginaw, Michigan. “In medical school, we’re not taught that.”

She said initiatives to bolster patient trust should be centered on improving those mechanisms.

“We can help on the clinical side, but we have to get the billing piece very transparent, very open and very correct,” Duggan said.

Geisinger’s Levy said transparency initiatives should go beyond prices and even the sharing of medical records.

“Our systems need to share more with our patients,” he said. “How we’re doing, how long are wait times, basic things that will make the day of the patient easier.”

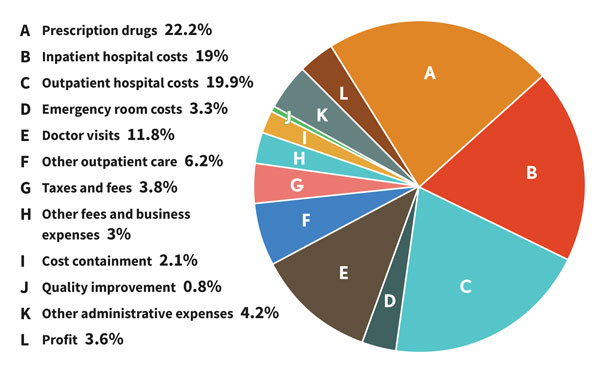

Where healthcare premium dollars go

Questions about affordability partially reflect concerns over how insurance premiums are directed. AHIP shared the following data during the Thought Leadership Retreat.

7. Improving equity

Mistrust in the healthcare system is felt most keenly by demographic groups that historically have lacked opportunities to receive high-value healthcare. The underlying inequity in access and health outcomes must be addressed as a precondition of building trust.

An important step is to further diversify the clinical workforce and other patient-facing staff.

“If you’re a patient of color and you see a physician of color, you assume to some degree that there is some equity in that system,” said Claude Brunson, MD, executive director with the Mississippi State Medical Association.

“We haven’t seen the diversity in healthcare, in people who are taking care of patients or in the system itself,” he added. “While we thought we were making a little bit of progress in [improving] diversity so that we could increase trust among patients of color, the pandemic came along and then that sort of imploded the whole [notion].”

Gender equity also remains an issue in some areas. Peter Angood, MD, CEO with the American Association for Physician Leadership, noted that slightly more than half of medical school classes are female, but in a specialty such as surgery, the share is only about 20%.

AHIP’s Lloyd said her association’s efforts to improve provider directories have included feedback from focus groups indicating that the diversity of a provider’s office staff is important.

“This is going to give us more homework [to gauge] how we think about what consumers want,” she said. “How do we display that in our directories … and how do we then think about networks and what we need to do to help shift our networks to meet what the consumer interests and needs are?”

8. Going digital

AI will be an increasingly significant presence in healthcare operations in upcoming years, and stakeholders are considering how to ensure the technology increases trust rather than diminishes it.

Digital medicine has the potential to improve healthcare, Neuwirth said. For example, statistics show the average primary care visit lasts 18 minutes, with the physician engaged in data entry or retrieval for more than 16 of those minutes.

“How do you build trust when your eyes are focused on a screen?” Neuwirth said.

Soon, he said, physicians will be able to interact more directly with patients while an automated solution creates better medical notes than any physician can. The technology will even be able to accurately read patients’ emotions.

“That’s the [type of] technology that’s going to rehumanize healthcare,” Neuwirth said.

Beyond technological concerns, Porter-O’Grady said, are the profound differences in leadership structures required for the digital age as opposed to the fading industrial age.

“We in healthcare are leading a multi-professional, multidisciplinary, interdependent, intersectional system that now demands a whole set of skills that are grounded in collateral leadership and complex adaptive systems,” he said. “So much of the leadership that we express is no longer relevant to the world we live in.”

No matter how tantalizing the possibilities, technology cannot be seen as a cure-all.

“Digital solutions aren’t going to solve our underlying problems,” Levy said. “We saw that with the EHR. You can’t slap a technical Band-Aid onto a bleeding wound and expect resolution.”

9. Easing systemic friction

An ongoing concern of both patients and clinicians is the type of roadblock to care posed by processes such as prior authorization.

Insurers and regulators understand the reasons for the frustration.

“From our perspective, prior authorization is really key to making sure that our patients are safe, that medicine is practiced [by] adhering to evidence-based care and that we’re keeping coverage affordable,” Lloyd said. “But we fully recognize the process is not so great and that we need a lot of improvement. We think that it needs to be here, but we need to make some changes.”

One initiative would promote electronic prior authorization. In a pilot incorporated by an AHIP member in Washington state, 89% of requests were instantaneously approved and none were instantaneously denied.

“It allows artificial intelligence to be used [so] you can go and pull the documentation out of the electronic health record — without the provider having to do it — and can even use natural language processing,” Lloyd said.

Rawal said CMMI and the Center for Medicare are looking at ways to test gold-carding in Medicare Advantage, giving providers a way to reduce their exposure to time-consuming prior authorization processes.

“When we’re thinking about reducing that provider burden and improving the workflow for providers, [prior authorization is] definitely something we should be thinking more creatively about,” Rawal said.

10. Acting now

Neuwirth acknowledged that ongoing financial pressures make implementing strategies to become more trustworthy all the more difficult. Yet stakeholders likewise may be reluctant to pursue fundamental changes when times are flush because they don’t want to alter a successful formula.

“The lesson is that it’s never a good time to make a difference,” Neuwirth said. “It’s never a good time to make things better.

“That’s the difference [with] real leadership, conscious leadership with integrity, courageous leadership.”

Neuwirth paraphrased the architect Buckminster Fuller, who referred to changing systems not by fighting them but by creating a new system that surpasses them. If legacy stakeholders don’t take necessary steps, disruptors that specialize in narrow segments of healthcare could win over growing numbers of consumers.

“I believe that the American public still trusts their providers and their provider systems more than these other entities. That’s a superpower,” Neuwirth said. “And you have your presence in the community. You have those ties, that legacy of relationship, of community service, etc. You have so much power in your people.”

But especially as older generations of healthcare consumers give way to millennials and Gen Z, “The thing about superpowers is you have to realize you have them and then you have to exercise them,” Neuwirth said.

“If you don’t exercise your superpowers, you’re going to lose them,” he added.

That’s why the solution roadmap must yield action.

“It’s time to stop admiring the problem,” said Robyn Begley, DNP, RN, CEO with the American Organization for Nursing Leadership. “Let’s get moving.”

Others echoed that sentiment.

“We can’t allow ourselves to be immobilized by the size and complexity of this problem,” Levy said. “We need to just start working on solutions and see where it leads us.”

Said HFMA’s Jordan, “It requires the desire to be better or — because this is healthcare, it shouldn’t just be ‘better’ — the desire to be great.”

Takeaways from attendees

Small-group discussions involving attendees, whose roles span administrative and clinical leadership positions with providers and health plans, are an annual staple of HFMA’s Thought Leadership Retreat. Here’s a sampling of the insights that came from the discussions on restoring trust in healthcare and from comments offered by attendees during the formal presentations.

Trust and organizational performance: For frontline workers, the visibility, accessibility and believability of executive leadership are critical factors. Employee satisfaction arguably is more critical than patient satisfaction because the former metric is how you ensure optimal care. Leaders need to make themselves consistently available, and if they do, employees will open up to them.

Digital health and technology: New technology brings the potential for improved accessibility and a better patient and clinician experience, but it requires good governance and a measured approach. Stakeholders must ensure such technology does not exacerbate disparities, given that not all hospitals have the resources to optimize its use and not all patients have access to or full awareness of how to use the technology.

Value-based care and holistic health: A sustainable model requires patient responsibility, meaning health education and help with navigation are pivotal. Engagement in such a model should include all stakeholders who influence health (e.g., public-health and community-based organizations). One question that remains is whether a high tide truly raises all ships or whether there instead will be distinct winners and losers in value-based models.

Transparency: Transparency is a systemic issue that goes beyond price listings and should encompass quality and strategies for prodding patients to shop for care. Commercial insurers have consumer-friendly apps that can make finding healthcare services more like a retail-shopping experience. Hospitals should be talking to their payer partners about the best way to leverage those tools.

Affordability: Affordability issues and medical debt collection practices are driving deferred care. Patient guidance and navigation at the front end of the financial experience are relatively easy steps that can pay big dividends. Patients may see the financial navigator as their most trusted liaison in the health system — more so even than their clinician. But finding the right people for those roles is a challenge.