Workforce of the Future

Empowered, more diverse and vulnerable to technology

By LOLA BUTCHER

The rules of engagement are changing for the healthcare workforce in multiple ways. Industry experts anticipate that younger generations are going to exert their will more strongly in the workplace, that employers will ramp up their efforts to hire people who better reflect their patients’ demographics, and that technology could reduce the need for certain duties and roles.

UMass Memorial sent all but a handful of its 1,000-person-strong revenue cycle team home in March 2020 because of the pandemic, and many are never returning.

Sergio Melgar, executive vice president and CFO, says the staffers seem to be more productive than they’ve ever been, and they seem to have a better quality of life from their perspective. “Many of them don’t want to come back, so we need to accommodate that.”

The unexpected work-from-home movement is one of many things that will reshape America’s healthcare workforce in the coming decade. Automation will lead to an administrative staff that will become leaner, more efficient and more skilled. Executive leadership teams will become smaller. The competition for staff members will become more fierce.

This decade will be a time of major transition for the industry, and senior leaders must take a systemic approach to guiding a changing workforce. “The healthcare leadership workforce is very aged, and I think we’re going to see a lot of retirees,” said David Salsberry, chief revenue officer at Texas Health Resources, Dallas-Fort Worth. “If we want our organizations to be successful, we’re going to have to engage not just the direct leaders impacted by these major change initiatives but also the next levels down.”

UMass Memorial Executive Vice President and CFO Sergio Melgar says staffers seem to be more productive in a work-from-home environment.

While the trajectory for some trends is clear, how some of healthcare’s biggest workforce challenges will play out is less so. One thing that experts do expect is that health system C-suites will have to become more diverse and better equipped to reduce racial and ethnic disparities — or their organizations will fail in the era of value-based care. Not a new problem; the industry has made little progress in the last 10 years.

Meanwhile, the health of the workforce — buckling under stress, burnout and trauma — must finally get the attention it deserves. Surveys earlier this year found at least a third of frontline healthcare workers have considered leaving the field entirely.

“This is the piece that’s important for CFOs to recognize: We know from national surveys that 50% of the workforce doesn’t feel valued, or feels only slightly valued, by their institution, and when that occurs, they are more susceptible to burnout,” said Corey Feist, CEO of the University of Virginia Physicians Group, the medical group practice of UVA Health. “If this doesn’t get fixed, you’re going to lose a workforce.”

Work-from-home is here to stay

The practice of working remotely has the potential to transform the healthcare workforce before 2030 rolls around. At Texas Health Resources, Salsberry projects nearly 100% of its financial administrative staff will work remotely before the end of the decade.

About a third of the entire financial administrative staff, including the majority of the revenue cycle staff, had been working from home before COVID-19 forced the issue, Salsberry said. Today, about 90% of his employees are working from home and like UMass, by and large, they won’t return to the office.

Employers and employees both find benefits from the work-from-home movement. At UW Health, the University of Wisconsin’s academic medical center, Robert Flannery, senior vice president and CFO, expects to downsize its administrative footprint significantly. Flannery said he anticipates going from three large administrative buildings to two in the near future, and the medical center may ultimately need only one. “We think there will be millions of dollars to be saved,” he said. “That cost comes out of our cost structure.”

ROBERT FLANNERY

Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, UW Health, University of Wisconsin

Larger talent pool

As work-from-home becomes standardized, the job market is expanding nationally for certain positions. “Some people who still like living in Wisconsin have more opportunities to work for organizations in states that are hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away,” Flannery said. “That’s now happening with our data analytics people. Our human resources team is rejiggering which positions we actually need to have more of a national market perspective versus a local or regional perspective.”

At UMass Memorial, the board of trustees has already discussed the potential to save money by recruiting staff in parts of the country that have lower wages. Melgar said doing so will require a thoughtful strategy. “If I do that, do I run the risk of having employees not be as loyal when somebody else comes in and offers to pay more?” he said.

Melgar thinks most of UMass Memorial’s administrative workforce will be based in central Massachusetts but, as UW Health is experiencing, workers with some skills will have a national job market to choose from. “This will be a potential drain for smaller, lower-salary markets that have very good technical people,” he said. “But I also have to be careful because if I don’t pay enough here, I will lose people. There’s always somebody somewhere that pays more than you.”

Retaining employees in the years ahead will require flexibility, Salsberry said. Texas Health Resources demonstrated that need when the pandemic closed schools and day-care facilities, forcing employees to juggle work and childcare. “As long as they got their work done on a given day, we didn’t care when they did it,” he said. “COVID-19 has resulted in our organization having to be a very different kind of employer to retain the staff we have and to attract talented staff from a larger geographical area. We are just now trying to fully embrace what that means in the near and long term.”

In some cases, work-from-home may lead to longer careers. An employee who has long dreamed of escaping cold Northeastern winters by moving to Florida, for example, no longer has to retire to make that happen. “They could go there and still continue to work for us,” Melgar said. “I think we’re going to get more years out of some of our employees than we would have otherwise.”

DAVID SALSBERRY

Chief Revenue Officer, Texas Health Resources

Automation, screen-scraping and bots

Health systems are going to look to technology increasingly, as smarter tools become more available. That means the healthcare sector is likely to devote the next several years to figuring out how robotics, automation and artificial intelligence (AI) can best be applied to administrative processes.

Most systems are only tiptoeing into the technology at this point, even though there is hope it holds promise. UW Health has found that automation and robotics have boosted efficiency in surgery, so Flannery expects that automation of administrative tasks holds the same potential. “Within the next six months, we will be implementing some of that technology for our revenue cycle team and our finance team as well,” he said. “I absolutely believe that it will provide significant opportunity for our organization.”

At Texas Health Resources, the system has used automated tools for screen-scraping and registering newborns with the state Medicaid department. It uses bots in cash management, making the process of posting and reconciling payments to the billing system and general ledger much more efficient and accurate, Salsberry said.

Still, he believes many AI products marketed for healthcare administration today are “a solution in search of a problem” and that vendors of AI solutions are reluctant to take on financial risk to prove their products are worth the investment.

“I can’t say that we’ve yet seen AI materially impact our worker productivity because I think it’s still very new,” he said.

He hopes that AI can deliver “exponential reduction in costs and improvements in quality” as technology develops. The system is evaluating an AI technology that analyzes how employees use the electronic health record (EHR) system and identifies repetitive tasks with the greatest opportunity to benefit from AI automation. Salsberry hopes this will allow the organization to be more strategic in selecting automation investments that deliver exceptional results.

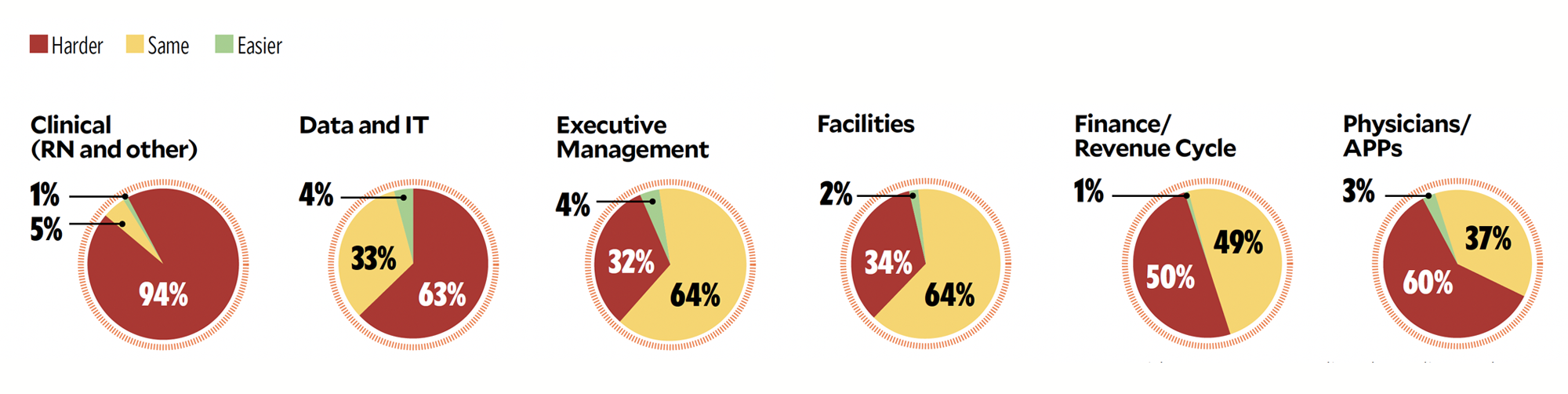

CFO SURVEY

Ease in finding qualified workers in the following areas (percentage of respondents)

COREY FEIST

CEO, University of Virginia Physicians Group, the medical group practice of UVA Health

Caring for the clinical workforce

America’s clinical workforce has been in bad shape for years — high rates of turnover, chronic shortages in some job categories, a burnout epidemic, mental health problems that workers fear acknowledging. Then came COVID-19, which required a huge swath of America’s healthcare workforce to risk their lives, often without adequate support from their employers.

It likely will take years to reverse the damage that’s been done, but providers must immediately start tackling the problem more strategically than they have in the past. They may, though, be surprised by how many nurses in total will be available.

“This is a workforce that has gone off to battle for a year, and seen repetitive trauma for a year, not just one isolated event,” said Feist, the University of Virginia Physicians Group CEO. “Now we have a population of employees who are more susceptible to mental health struggles.”

The health of the clinical workforce is of CFO-level concern because it affects the organization’s core operations. A burned-out workforce is associated with a 200% increase in medical errors, Feist said. And just maintaining adequate clinical staff has become a serious problem. “We’ve seen a huge walkout of the workforce,” Feist said. “I don’t know a system in the country that has sufficient nursing staff.”

CFOs can direct investments in “true workplace interventions to redesign the healthcare environment” that can mitigate burnout, he said. Beyond that, other administrative burdens that sap clinicians’ time and energy must be minimized. “We’ve got to push back all of this bureaucracy and get it out of the hands of the doctors and nurses,” he said.

Behavioral health demands will continue to grow

Health systems are only now grappling with the trauma their staffs have experienced, and immediate action is essential. Mental health issues, which are stigmatized throughout society, are even more taboo among clinicians who worry that seeking diagnosis and treatment might imperil their license or their defense against malpractice claims.

CFOs can help in two specific ways: Ensure their community has mental health services to support the growing demand. And for the benefit of their own staffs, support insurance plan designs that allow employees to seek mental health services outside of their own facility, which otherwise can be a barrier to treatment.

Feist also encourages healthcare executives to push for safe-haven programs — already in place in Virginia and some other states — that protect healthcare professionals from having their mental health and medical records disclosed as evidence in malpractice lawsuits. Such programs require a membership payment for individual clinicians, which health systems can pay for. “Funding solutions that support the mental health of the workforce that are incremental to those that are already in place are essential,” Feist said.

JOHN BLUFORD

President and Founder, Bluford Healthcare Leadership Institute

Lack of diversity will hit the bottom line, quality of care

Years of inaction to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities have put hospital executives in a position of needing to act quickly if they are to remain viable in the coming era of value-based care.

Until now, most health systems have failed to make the connection between diversity in the C-suite and the social determinants of health that drive those disparities, said John Bluford, former president and CEO of Truman Medical Centers and former chair of the American Hospital Association. A decade ago, Bluford, along with the leaders of America’s other top healthcare associations, issued a call to action: Diversify the healthcare workforce and eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities.

“Even though there has been a focus on increasing the diversity of the workforce, we have made little progress. Not nearly enough,” Bluford said.

Today, as leader of the Bluford Healthcare Leadership Institute, he has worked to introduce minority undergraduate students to healthcare administrative leadership and help them launch their careers. He estimates that perhaps 14% of healthcare administrators in C-suite positions are Black or Hispanic, compared to a minority patient base of 32%.

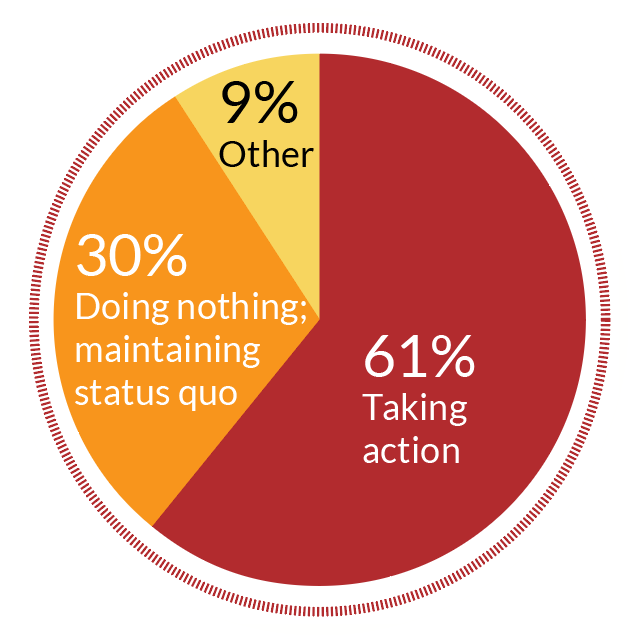

CFO SURVEY

Diversity, equity and inclusion changes:

But the COVID-19 pandemic made apparent America’s longstanding failure to eradicate disparities. An analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the death rate per 10,000 patients was 5.6 for Black and Hispanic patients, 4.3 for Asian patients and 2.3 for white patients. Lip service must be replaced with action now, Bluford said.

If the industry doesn’t respond to the inequities revealed by the pandemic, then the next 10 years is going to be rough. CFOs must recognize that improving the health of historically marginalized groups is essential to financial success in value-based contracts, said Duane Reynolds, CEO of Just Health Collective, a consultancy working to build health equity.

“Population health is here to stay, and the industry has said value-based care is where we are headed,” he said. “If organizations are not prioritizing resources geared toward advancing health equity, diversity and inclusion, they are going to be challenged.”

Creating a new position — chief health equity officer or chief diversity and inclusion officer, for example — may be a first step, but only that. “This is not one person’s responsibility,” Reynolds said. “You, as the CFO, should understand the social determinants of health that are going to impact your organization financially. And you, as the CFO, have to be thinking strategically.”