Optimizing Physician Referrals: A Key to Successful Population Health Management

The cornerstones of an effective population health management strategy are developing a high-functioning specialist referral network and fostering consistent use of the network by the referring physicians.

To effectively manage the health of a population, a provider organization must develop strong capabilities in many areas and activities. A key success factor is having the ability to apply a single type of clinical decision appropriately and effectively across multiple patients. Nowhere is such an exercise more important or scalable than in the management of the physician referral process.

Traditionally, for a physician, a referral involved nothing more than giving a specialist’s business card to a patient. Success in value-based care will require that referrals be managed not just on familiarity or word of mouth, but also with the same rigor and attention paid to other aspects of health care. In this era of accountable care, a provider organization’s referral network should be defined by data analytics and outcomes. Without a high-functioning referral network, it is almost impossible to deliver high-quality results and a consistently positive patient experience.

Understanding Referrals

To develop such a referral network, the organization must understand factors driving its referrals: why the referrals are initiated, who makes the referrals, and who are the recipients of the referrals. Put more simply, the question is, Why is this physician referring that patient to that specialist at this time?

Unfortunately, silos that have built up among providers have obscured this process and the factors shaping it. The separation of hospital- and office-based physicians, the elimination of physician lounges within hospitals, and the overall decline in the casual “curbside” consult all have contributed to these silos of care. Silos among primary, specialty, and ancillary care providers promote inefficiency and duplicative services and, most important, lead to a suboptimal patient experience.

Healthcare provider organizations require data and analytics to break down these barriers that stand in the way of developing a high-functioning referral network. Data can provide physicians with clear insights into why and when patients should be referred for specialty care and to whom they should be referred, thereby making the referral process easier, improving professional satisfaction, and driving better clinical results.

Success also depends on defining and utilizing a high-functioning network, which is critical to ensuring patients receive the right care at the right time at the right place.

Putting patients first in the development of a referral network drives the communication and teamwork necessary for the best possible outcomes. A patient-centric referral process requires that good communication be maintained between primary care physicians and specialists throughout the process, and the presence of such communication can be a determining factor in the patient clinical outcome. With the high cost of health care, providers who understand and effectively use the referral network can help lower their patients’ out-of-pocket expenses while optimizing their clinical experience and outcomes.

Characteristics of High-Functioning Networks

Health care is always local, but all successful referral networks share certain characteristics in common regardless of local differences.

Good communication. Effective communication is a two-way street. It is imperative that communication always be timely and accurate among clinicians. Specialists can educate primary care physicians on what treatments or work-ups should be completed before a referral is made, especially for common problems. Primary care physicians should share with consulting physicians the results of any completed work-up and any expectations they may have discussed with a patient or the family. After a consultation, a specialist should inform the primary care physician regarding treatment options discussed with a patient, all pertinent clinical findings, and any planned testing or procedures. Patients expect their physicians to communicate—and ensuring that this expectation is well understood by the physicians on both sides of the referral can go a long way to meeting that goal.

High-quality referrals. A high-quality referral occurs only after three circumstances have been reached:

- The primary care physician has exhausted his or her clinical skills

- An appropriate specialist has been identified

- The patient understands clearly why the referral is needed and what treatments or procedures he or she can anticipate

Any long-term quality plan should include measuring and monitoring each of these conditions of a referral.

High efficiency with respect to sites of service. Networks can be measured on clinical quality, ancillary utilization, and site of service. High- quality networks use the lowest-cost and highest-quality sites of service. A routine colonoscopy for a patient whose condition is uncomplicated can be performed at an outpatient facility, with hospital-based colonoscopies being reserved for patients with complicated conditions. Identifying variability among these measures allows for identification and dissemination of best practices.

Emphasis on high ability, affability, and easy access. Patients and physicians expect their specialists to be highly skilled, easy to communicate with, and easy to access. An organization should monitor the time it takes for patients to obtain specialty appointments and then expand its preferred network as demand increases. It is critically important that specialists in the network be willing to routinely provide phone consultations, institute convenient office hours, and be able to accommodate same-day appointments.

A focus on consistent improvement. Organizational leaders should continuously monitor the referralnetworks for access, utilization, and communication, especially given that practice patterns tend to change over time, sometimes for the positive but sometimes for the negative. For example, if a specialist moves from in-network to an out-of-network ancillary, it is important to register that change quickly.

Challenges to Success

The most challenging part of developing a specialty referral network is taking a hard look at the actions and expectations of the referring and receiving providers.

Knowing when to refer. Primary care providers should be asked always to consider a fundamental question: Is the referral necessary, or is the care better handled in the primary care office? Referring physicians might view this question positively, as an opportunity to identify areas to expand their clinical skills. But specialists may view the question as encouragement to primary care physicians to encroach on their territory, leading to a decline in their “bread and butter” consults. Conversations on when and why to make a referral can be uncomfortable and even disruptive to longstanding referral patterns, but if this communication does not happen, the only losers are patients. Physicians need to keep in mind that these types of conversations are necessary for highest-value clinical results.

A successful referral management strategy, therefore, starts not after the referral is given, but well before. The referring physician must be aware of, and understand, what type of clinical work-up should be completed and when a clinically appropriate treatment should be tried before a referral is made.

At Village Family Practice in Houston, for example, physician leaders studied referrals for imaging with a complaint of low back pain in the first six weeks of symptoms. The findings disclosed considerable variability of clinical practice across physicians, prompting the leaders to provide focused education for the physicians on when a referral would be appropriate for either imaging or orthopedic consultation.

Ensuring all physicians acknowledge the importance of communication. Communication from the specialist to the primary care physician also is critically important. Clinical studies consistently have shown that once a referral is initiated, a referring physician receives documentation about that referral visit less than 40 percent of the time. Primary care physicians understand how this lack of communication results in coordination of care, but all too often, specialists do not recognize the value of a primary care home and the pivotal value a primary care physician provides in helping to maintain the patient’s health. It is imperative that specialists be vetted for inclusion in the referral network. Specialists need to understand and be willing to provide timely and pertinent communication with the primary care providers, recognizing its importance in effective care coordination.

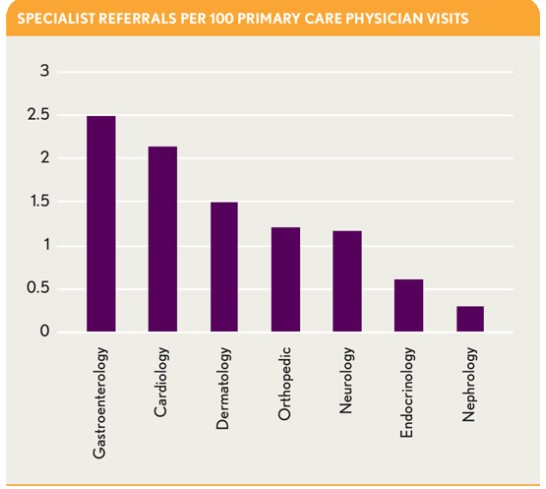

Promoting consistency in referral patterns. Another indicator of a low-performing referral network is undue variation in referral patterns among providers. To address this problem, Village Family Practice measures each primary care physician’s referrals to each specialty per 100 office visits. Early in this process, the practice leaders noted three- to four-fold differences among primary care physicians in the frequency of referrals. This variability occurred not only in higher-acuity areas such as cardiology and orthopedics, but also in lower-acuity areas, such as dermatology, allergy, and podiatry.

Where such a high degree of referral variation exists, there always is an opportunity to improve the quality and efficiency of care. For example, if a physician is referring twice as many dermatology cases as a colleague, it may be an opportunity to educate and expand the physician’s clinical capability. To optimize referrals, it is necessary to understand not just the frequency but also the reasons why.

Promoting a cost-conscious mentality. According to data from 6,000 commercially insured patients across Houston-area primary care practices within the VillageMD network (the primary care network of which Village Family Practice is a part), specialty physician costs constitute about 20 to 25 percent of total medical expenses, compared with about 5 percent for primary care. Building referral networks that perform with optimum efficiency, therefore, is critical to adhering to the principles of population health management.

The ability of primary care physicians to contain costs depends in large part on their awareness of where specialty services are being performed. The VillageMD data indicate that, within commercial populations, procedures and diagnostic tests often cost less when performed in an outpatient facility. (Differences in costs will vary by region, primarily due to access issues.)

The data indicate the following cost differences, for example:

- An endoscopy performed in a hospital facility costs twice as much as an endoscopy performed in an ambulatory surgical facility.

- A computed tomography (CT) scan performed in a hospital facility costs six times as much as a CT scan performed in an outpatient freestanding imaging facility.

- An magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed in a hospital facility costs more than twice as much as an MRI scan performed in an outpatient freestanding imaging facility.

Role of the Physician Leader

An organizational effort to identify a specialty network will invariably expose longstanding inefficiencies and ruffle some feathers, especially if some specialists are excluded from the network. The problem is, however, that specialists often are excluded from networks without a clear understanding of why. The reasons for inclusion or exclusion should be made clear in every case, because colleagues always should have the right to receive both positive and negative feedback on their performance.

To address such issues and reduce the friction that can impede efforts to build an effective specialty network, the organizations should identify physician leaders in both primary and specialty care and engage them early in the network development process. These physician leaders can provide critical information by reaching out to the primary care base to understand which specialists meet their needs and which do not, and why. The primary care physicians know who takes their phone calls, fits a patient in at the end of a day, and includes them in the management of mutual patients, and they know who doesn’t do these things. An effective physician leader needs to be able to share expectations and results with a specialty network.

Primary care physicians focus on the quality, accessibility, and timeliness of the care their patients receive. A specialist’s focus should be on seeing patients that truly need their specialty skills. The benefit to the patient is obvious: high quality, efficient clinical care provided by the right physician at the right time. Unless primary and specialty physician are actively engaged in network development and truly believe their voices are heard, they will vote with their pens and continue to refer outside of a defined network. Physician leaders are the key to fostering such engagement.

Data and Analytics

Data and analytics play a key role in the development and use of a referral network. Being able to provide data back to a physician about the number of referrals he or she makes by specialty, who those referrals go to, and which specialists can be relied upon to communicate in return is the most effective way foster more appropriate referrals and adoption of a preferred network.

Over time, analytics can be used to identify the most accessible and efficient providers within a network. Then, physician leaders should be willing to share the good news with those who retain a place in the network, while also being sure to share the bad news with those who fall short of expectations.

The electronic health record and claims data are sources for historical data. Village Family Practice uses a simple proactive strategy to direct referrals to the practice’s preferred network. Using a scheduling technology, the practice’s physicians can schedule specialty appointments directly into a specialist’s schedule, at the time of referral, relieving patients of the challenge of scheduling a specialty appointment and allowing the physicians to more actively direct patients to a preferred network. Progress notes, labs values, and insurance information are sent at the time of referral, helping the specialist avoid duplicative testing and to address any insurance requirements prior to seeing the patient. The practice receives feedback on patients who do not complete a referral and can identify those specialists who do not return consultation notes or communicate with the primary care practice after the patient is seen.

Village Family Practice found that, in the area of high-end imaging, imaging completion rates increased from 50 percent to more than 85 percent as a result of scheduling patients’ appointments at the time of referral, and a significant majority of those increased visits were completed within a week of referral.

Once a successful high-functioning network is in place, physician leaders are in the best position to influence utilization of that network. The ability to share data on quality, accessibility, and communication—as well as on cost and patient satisfaction—with referring physicians at a peer-to-peer level is the surest way to elicit increased acceptance and utilization of the network.

Driving Performance

Physicians complain about poor communication and fragmented care, but they all too often are themselves contributing to the problem. Open and honest conversation between primary care and specialty providers is imperative to clinical success in caring for patients. Conversations can be difficult, but if they are driven by data and scheduled on a regular basis, they provide an important means for promoting coordination and communication throughout the system.

Developing a high-functioning specialty network and measuring physician referrals to the network are critical to achieving effective population health management. With the goals of enhanced coordination, elimination of duplicative services, and an improved patient experience, such a network improves patient care by giving referring physicians a clear understanding the why, where, and when of referrals to specialty care. And ultimately, the ability to identify appropriate sites of service, engage physicians, and identify and utilize a specialty network provides the foundation for a successful population health management strategy.

Clearly, the days of referral by word of mouth and business card are, or should be, over. Instead, the goal should be to form a high-functioning physician referral network that provides value to its community of patients and providers through a focus on the Triple Aim: improving quality, reducing costs, and a providing positive patient experience.