Best Practices for Affiliation Agreements Between Health Systems and Universities

Health systems and universities seem to be at constant odds, stuck in perpetual negotiations despite having long-term affiliation agreements. Whether the debate is over faculty recruitment packages, purchased services and program support agreements, payment for graduate medical education, or the myriad other issues that academic medical centers (AMCs) must address, there is a tendency to get trapped in a transactional relationship characterized by one ad hoc deal after another.

At the same time, the size and scope of funding arrangements between university medical schools and their affiliated teaching hospitals and health systems continues to increase. As a percentage of total revenue, medical school funding from their affiliated hospitals and health systems has more than doubled from 7 percent in 1981 to 18 percent in 2017. a

From a health system perspective, funds flow outlays to university affiliates represents a significant portion of the operating budget: A recent survey of 55 AMCs found that health system funding to their affiliated university or medical school partners averaged 8.4 percent of their net patient revenue. b With hundreds of millions of dollars at stake over the course of decades-long agreements, and with large-scale affiliations continuing to be announced in recent years (e.g., Geisinger Health System and Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine in Pennsylvania, ProMedica and the University of Toledo in Ohio, Hackensack Meridian Health and Seton Hall University in New Jersey, RWJBarnabas Health and Rutgers University in New Jersey and Banner Health and the University of Arizona), it is vital that organizations critically evaluate their affiliation agreements and the associated funding arrangements to ensure that they are well positioned to advance their partnership objectives.

Symptoms of a suboptimal affiliation relationship include the following:

- Limited or inconsistent understanding of the bidirectional value of the relationship, financial commitments, and/or the inherent interdependency of the parties

- Lack of a formalized process for agreeing to and funding new programs or business development opportunities

- Inability to organize quickly to capitalize on market opportunities

- A lack of coordination that too often results in missteps and duplication

- More time spent on contract management than on strategic planning and/or execution of mutually agreed-upon priorities

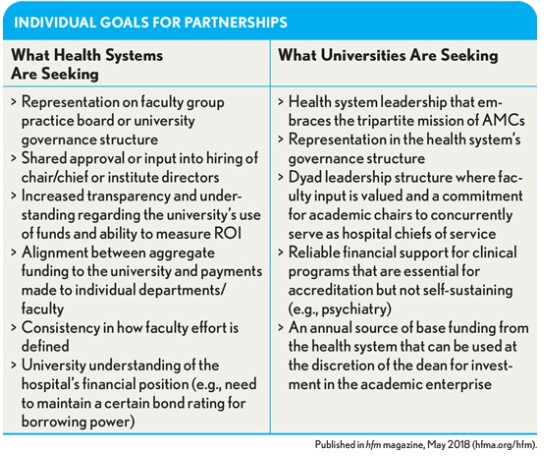

A contemporary and well-structured health system-university affiliation agreement is one that clearly articulates the value of the partnership, defines key commitments and accountabilities, and addresses the needs of each parties (as shown in the exhibit below) while enabling execution of joint strategic priorities.

Following are seven critical features that should be included in all affiliation agreements, either as amendments to existing agreements or as part of new definitive agreement(s). These items will have relevance for all AMCs regardless of organizational structure, but they are most applicable in cases whereby the university and health system are not corporately integrated. Also influencing how these elements may be applied is the structure of the faculty group practice (FGP) and other employed or affiliated physician organizations (as discussed in greater detail later in this article).

Functional and Highly Active Affiliation Committee

Affiliation agreements should be designed to foster strategic and financial alignment between the organizations across mission areas while recognizing that that both individual and mutual goals will evolve over time. A high-functioning affiliation committee comprising senior leadership from each organization is essential for navigating these changes.

Although specific responsibilities will vary, the affiliation committee should lead joint strategic planning and faculty recruitment efforts, prioritize major investment or program development opportunities, and ensure an appropriate sub-committee or task force structure is in place to monitor key functional areas of relevance to the partnership (e.g., finance and operations). Furthermore, the committee may need to bridge cultural gaps between universities and health systems, lead major change initiatives, and ensure that the needs and priorities of each organization are considered in a decision-making process that moves the entities in a unified direction.

Cross-Representation in Governance

In addition to the important advisory role played by the affiliation committee, many organizations are taking steps to create meaningful opportunities for participation in their respective governance structures, typically by designating seats on one another’s boards and/or board committees (e.g., the health affairs committee of a university). The number of seats is largely dictated by the existing board/committee structure, including any legal or regulatory considerations (e.g., in instances where board members are political appointees), but the overall degree of influence should be equal for both parties and commensurate with the scope of the affiliation and nature of the overall partnership. In all cases, the intent of this cross-representation is to ensure that implications for the AMC partnership are considered in decision making at the highest levels of both organizations.

Matrixed Reporting Structures for Executives

Universities and health systems also should take steps to ensure that appropriate joint management structures are in place to align day-to-day operations between the entities. One strategy is to develop leadership positions with matrixed reporting relationships to both the health system and university or health sciences center, such as senior physician executives that hold dual roles in the health sciences center (e.g., vice chancellor of clinical affairs) and the health system (e.g., executive vice president for medical affairs). Similarly, it is standard practice among functionally integrated AMCs for academic department chairs to serve concurrently as the chiefs of their respective departments in the hospital or health system. The goal of these dual roles and matrixed reporting relationships is to create an environment where leaders must balance the interests of both organizations and the often-competing demands of their collective academic and clinical enterprises.

Joint Program Development and Exclusivity

Parameters for joint planning and program development should be a central component of any major affiliation agreement, including clearly defined terms related to exclusivity. Mutual exclusivity between two parties enables the greatest degree of collaboration, transparency, and shared decision making. However, this is not immediately feasible for many AMCs (e.g., those with universities that rely on multiple health system partners to train medical students and residents, or geographically dispersed health systems with significant private practice physician relationships in some markets). In these cases, the parties may elect to grandfather-in existing relationships and/or to limit exclusivity to specific departments/programs or within certain geographic boundaries (e.g., the health system serves as an exclusive academic partner and training site within a predetermined service area). For new programs, the parties should consider right-of-first-offer provisions to ensure that possibilities for collaboration are exhausted before moving on to a third party.

Performance-Based Funding Arrangements

However well intentioned, joint strategic planning and management efforts are likely to fall flat unless financial interests are aligned among the university, health system, and clinical faculty. Organizations should take steps away from a primarily transactional relationship (often characterized by an overwhelming number of inconsistent contractual arrangements) toward a more globally defined, performance-based payment mechanism, with shared risk/reward and clearly designated funding lanes for clinical and academic activity.

With respect to clinical funding, one highly effective vehicle is to pool all clinical revenue at the system level (which allows for joint contracting with health plans) and, in turn, distribute funding to the hospitals and faculty/physician organization or departments through a performance-based methodology that rewards productivity, access, quality and safety, and cost-efficiency. Similar approaches should be considered for graduate medical education and mission support funding. For example, there is a clear trend toward shared-risk models for mission support that link discretionary funding to predefined metrics or the financial performance of the AMC. Specific metrics and targets will change as organizational priorities shift and adjust to the market, but the underlying principles and mechanisms should remain transparent, formula-driven, and performance based.

Consistency Across the Physician Enterprise

The percentage of physician practices owned by a hospital or health system surged from 27 percent in 2006 to 79 percent in 2016. c Depending on the disposition of the FGP (which may be separately incorporated or exist as a subsidiary/business division of the health system or medical school) and/or the structure of the nonacademic physician enterprise (i.e., nonacademic physicians employed or affiliated with the health system), health systems and universities will face different issues regarding how best to organize their combined physician enterprise.

Although a discussion of the full range of physician enterprise organizational and corporate structures is beyond the scope of this article, the following questions should be addressed as part of the affiliation agreement development process:

- What structural option best supports organizational and financial integration of the clinical enterprise (i.e., the combined assets of the teaching hospital/health system, FGP, and nonacademic physicians)?

- How should physician leadership be engaged to promote shared accountability across the medical school, FGP, and health system (e.g., through appointment of a single physician leader over the academic department and corresponding hospital department/division and/or service line/center)?

- What are the criteria for determining recruitment into academic or nonacademic physician practices?

- How will physician compensation and benefits be structured in an equitable manner that recognizes differences in practice orientation?

- How will physician practice infrastructure be managed to create efficiencies and avoid duplication?

- How will consistent performance standards be implemented across sites of practice?

Regardless of the organizational structure, the parties should seek to promote consistency across the physician enterprise so that providers have incentives to deliver high-quality, patient-centric care in the best interest of the AMC and independent of academic orientation or site of service.

Branding and Philanthropy

As competitive pressures continue to mount, branding and philanthropy will become an increasingly important source of competitive advantage for some AMCs. Unfortunately, because these elements often are overlooked in affiliation discussions, many agreements fail to adequately address the range of potential issues that the affiliated entities may face. One such issue is how existing brand assets (e.g., university or health system name and visual identity) can be combined into a compelling and differentiated brand strategy that represents the AMC while preserving the identity and brand equity of its component entities. From a philanthropic standpoint, organizations often face potential conflicts when pursuing gifts from grateful patients that have been treated by university faculty in a health-system-owned facility. Affiliation agreements should include clear guidelines and processes to navigate these decisions and ensure that efforts are coordinated and the combined resources of the AMC component entities are fully leveraged.

As the healthcare market evolves, affiliations will continue to be negotiated and renegotiated. Health system reconfigurations, market competition, new medical schools, clinical campus expansions, and national economic priorities will all impact the landscape of academic affiliations. Organizations that have taken the time to design and adopt thoughtful affiliation frameworks will be well-positioned to act together in an aligned and mutually beneficial manner to pursue new opportunities. Nimble partnerships will result in strategic advantages to both parties and create measurable value.

Footnotes

a. Association of American Medical Colleges, “Revenues for the General Operational Programs of U.S. Medical Schools,” AAMC Data Book, May 1990; Association of American Medical Colleges, “All U.S. Accredited Medical School Revenue by Type, $ in Millions,” AAMC Data Book, 2017.

b. Includes funding for clinical operations, medical direction, graduate medical education, and other academic support. Source: University HealthCare Consortium, 2013 survey of 55 participants.

c. Derived from Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) Physician Compensation and Production Surveys, 2007 and 2017, based on prior year data.