Why owning a health plan is a good provider strategy

In 2018, roughly one-third of U.S. health systems offered some form of health plan product. Many have experienced some early stumbles, but this trend is highly likely to grow.

Despite a stubborn adherence to fee-for service (FFS) as the primary payment model in many quarters, it is clear that the nation’s transition from FFS to a value-based payment model will continue. Facing ongoing declines in FFS procedures such as inpatient surgeries, U.S. health systems are increasingly recognizing the importance of having their primary focus be on health and health outcomes rather than on the number of visits or procedures.

This recognition has prompted a growing number of health systems to consider off ering health insurance plans to help them grow revenue from covered lives.

Done correctly, this strategy has upsides for all parties. Health systems receive a new revenue stream as they transition away from FFS income while also creating an incentive for health plan members to stay within their care system.

For consumers, having healthcare and health coverage under one roof means fewer headu0002aches and less bureaucracy, such as the need for prior authorization of physician-recommended procedures.

For providers, having more patients use the same, system-provided plan lowers administrau0002tive burden and reduces losses from unreimbursed care.

Key strategic considerations

Providing coverage along with care makes sense for nearly all health systems. But there are many factors that a health system should consider before deciding to move ahead with a provider[1]owned health plan, including the following.

1 Assess your network readiness. Owning a health plan is not appropriate for health systems still deeply focused on acute and hospital-based care with limited investments in ambulatory and post-acute care services. Likewise, health systems must possess, or have the ability to create, a sufficient care delivery network for the members of the plan.

2 Determine whether to go it alone or find a partner. When stepping into the role of an insurer, pursuing a partnership, joint venture or a mix of the two can help smooth the way, shorten the learning curve and prevent expensive missteps. Partnering initially with a well-known, respected insurance provider can help a health system better understand how a successful insurance division should operate, how to design health plans that appeal to consumers and how to drive growth through this strategy.

Having a network of partners is an effective solution. In addition to collaborating with an experienced insurer, a health system can partner with trusted brokers who know how to market consumer plans directly and through physicians. A partner with experience in providing inbound calling support to educate consumers about health plans can be invaluable, particularly if the plans include Medicare or Medicaid. When calling the plan, members need an option to talk to a human and not a seemingly endless series of voicemail prompts.

How to find a potential partner

Evaluating a potential partnership to enter into the health plan business raises many considerations regarding fit. The following are some important questions to consider:

- Does your potential partner share your vision and expectations for the partnership?

- Is the potential partnership of relatively equal importance to both organizations?

- Will the partner create a path for growth that is not otherwise readily available for your organization?

- Does the partner bring capabilities that you do not possess and/or that are not easy to develop on your own?

- Will the partner share the economics in a symmetrical manner (e.g., you both win or lose together)?

- Will the partner invest in the people, process and technology required for success?

- Is the partner willing to develop a fair process to resolve inevitable disputes or disagreements?

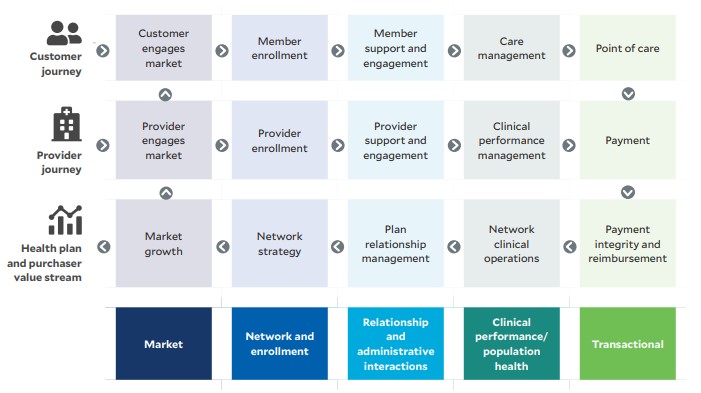

3 Make sure you have the necessary infrastructure. Striking the right strategic balance is important for the venture’s infrastructure. At a strategic level, the health system should look for ways infrastructure can differentiate the health plan from its competitors in market. Those advantages may be found in the network and enrollment process, in relationship and administrative interactions, through clinical performance and population health management or even in the transactional processes throughout the customer journey, as depicted in the exhibit below.

Health plan value creation process

At an implementation level, the health system’s front-, middle- and back-office infrastructure must support insurance product design, sales, service, analysis and evaluation. Ideally, the health system will build some elements, the insurance partner will build others and the two partners will build the rest together.

4 Ensure you have a good plan and the right people in place. The infrastructure of the health plan is inevitably linked with the people, and a successful business plan will help connect these dots and keep the entire entity focused. Having a clear mission, vision and strategic plan is critical. Everyone involved must understand — and be reminded by leadership — why the health plan was formed, what its goals and outcome measures are, and what the organization wants the plan to look like in five to 10 years.

Having the right people is crucial to the health plan’s success. The venture will require leaders experienced in insurance, government health plans, actuarial science and health plan marketing and customer service — and with a knowledge of healthcare delivery and population/panel health management. The venture’s leadership and staff will likely be a mix of new hires and existing staff from both partners. Whenever possible, existing staff expertise from both partners should be tapped to keep the venture lean and avoid excessive overhead.

5 steps to designing successful health insurance products

To ensure the path to success is as smooth, short and inexpensive as possible, the health system should use a five-step foundational approach in designing the health plan’s insurance products.

1 Balance the health plan’s benefits. Consumers want affordably priced health plans offering a rich set of benefits. Failing to correctly balance these preferences can result in poor initial sign-ups, low growth or losses from inappropriately priced plans. For each health plan product, the health system should be specific in defining its target market, be clear-eyed in how competitive that market is and be strategic in how best to enter it. Entering the wrong market with the wrong investments or without a sustainable model is a recipe for failure. Look thoroughly at what’s already in the market and be willing to build plans that consumers already want. Attempting to change consumers’ preferences is a much riskier path.

2 Keep it simple at the beginning. It’s a mistake to try to design a diverse set of plans right out of the gate. Although jumping right in by offering plans for multiple markets — e.g., commercial insurance, Medicare and Medicaid — might be tempting, such a strategy can quickly become overwhelming. Instead, creating a single plan is the smartest first step for most health systems. Perfecting one plan’s design, internal operations and collaborative operations is a critical first step before trying to move on to offer more insurance products.

3 Diversify plan offerings gradually. Over time, however, any health system that is serious about insurance as a cornerstone of its strategic growth will likely work toward building a strong menu of plans, including HMOs, PPOs and point-of-service products. Diversity in plan offerings will appeal to the widest range of potential customers, including those with employer-based insurance; those eligible for Medicare, Medicaid or exchange-marketed plans; and those of various ages, with various incomes, family sizes and health needs.

4 Begin cross-selling other plans to members as plan membership grows. For instance, members are most likely to move into a new HMO product if they’re already members of another of the health system’s plans. For commercial insurance, most health systems would prefer that everyone enroll in the plans most centered on their own networks. But not every employer or consumer will want that, so an effective strategy might be first to attract members to a broader network and then in the next year work toward convincing a third of them to move into a narrower network, and the following year, 50%, with the goal of having everyone be in the preferred network by year four or five.

5 Work toward a diverse menu of plans. Overall, there are few drawbacks for health systems to building a menu of plans. That decision will depend in part on how wide a net must be cast to draw in desired customers. Limiting the number and types of plans offered will restrict the health plan’s customer base, which for example may be just 3 million people versus 7 million with a full menu.

Phoenix-based Banner Health, for example, now participates in all three major lines of insurance business — Medicare Advantage, Medicaid and commercial — and it has recently launched products for state and federal health exchanges.

How provider-owned health plans promote value

When health systems offer a range of health plans that draw a large number of members, there are also longer-term benefits for physicians and plan members. It aids physicians in their transition from FFS medicine to a value-based, population health management approach. Consumers benefit similarly, as health systems and physicians transform to focus less on transactional care and more on health.

It’s one thing to effectively manage diabetes and help people control their A1C. It’s another to help prevent diabetes in the first place, which is what the whole U.S. healthcare system is driving toward. This transformation will not happen overnight, but it will happen. Consumers will benefit from improved health — and health systems offering coverage plans are a key to that change. (For an additional discussion of risk considerations, see the sidebar “Taking on full risk,” below.)

Ultimately, acute care organizations are geared toward the critical work of helping patients with immediate issues that must be addressed. embarking on a health plan strategy requires a more holistic view of members, not patients, with a focus on the overall wellness of the population being covered. Health plan strategy is not just about investments in infrastructure and skills, it is also about creating a different organizational mindset regarding value. For health systems that successfully add this element to their existing ecosystem, the results can be a truly well-rounded and comprehensive approach to delivering health and healthcare.

How to form and manage partnerships to launch a provider-owned health plan

The strongest health systems to enter into insurance partnerships will be those with richly integrated networks and prominent market positions in their region. An insurance company is unlikely to partner with a health system that cannot support all the healthcare needs of a health plan’s members. For Phoenix-based Banner Health, it took nearly 20 years to build to the point of being able to deliver the necessary scope of care to health plan members.

When seeking an insurance partner, health systems should consider two key criteria:

- Strengths: Do both parties bring something unique to the table?

- Culture: Do both parties have what it takes to get through the rough spots?

Assessing strengths

The insurance partner should complement the health system’s strengths. If a health system is good at medical management, the best insurance partner will be strong in distribution, marketing and sales for that area. The health system should consider this question product by product. For commercial insurance, a national insurance partner will expand the pool of potential plan members.

Banner Health, for example, began its journey into commercial insurance in 2016 through a joint venture with Aetna. In what has proven to be a successful partnership, Aetna brought a very respected national insurance brand to Banner’s strengths in clinical care.

Reviewing cultural compatibility

Not every organization can be a good partner. Healthcare is littered with failed partnerships. The health system therefore should look for evidence that the prospective partner has been successful in partnering.

Defining and valuing roles

After identifying a partner, both parties must be fully coordinated on responsibilities, and it is essential to put these details in writing. In a matrix, all roles (e.g., care management, sales/ marketing, customer service) should be listed and defined and responsibilities assigned between the partners based on who is best qualified for each role. All roles should be tied back to the partnership’s goals. Then a reputable third party should be used to value each role, determining what it should cost to competently provide that service, so the partners are not in a perpetual state of negotiation. Partnerships can falter if they approach this step like a contract negotiation. A win is not pushing your partner to a lower price or standard. A win is doing whatever it takes for the venture’s success, delivering to agreed-upon standards at an agreed price point.

Anticipating change

It also is important to plan upfront for major changes, such as new leadership on either side. The partnership should be set up so that it makes sense no matter who is running it. Its principles, expected outcomes, growth and financial performance must make sense to new leadership or even a new organization. After Banner|Aetna was formed, CVS bought Aetna, but the joint venture survived because it was well constructed.

On the other hand, should the partners be found to have different, incompatible strategies, there needs to be a way to unwind the deal. It should not be easy to unwind, but should that need become unavoidable, the unwinding should be equitable. Get an external valuation. Put in writing what happens if the partnership dissolves.

Taking on full risk: Lessons learned from forming a provider-owned health plan

In 2020, Banner Health in Phoenix felt confident enough in its people, infrastructure and experience to take a significant leap forward – underwriting and taking on full risk and assuming full accountability for health plan members’ health outcomes. Because the health system had a solid foundation, this new phase has proved successful: The health system is assuming even more capitated risk in 2022, and it has a stated goal of having 50% of its revenue come from insurance premiums within five years.

Taking on full risk brings two key benefits: flexibility and the ability to further facilitate the evolution away from fee-for-service (FFS) revenue.

Flexibility comes from being able to take full advantage of the integrated health system and from obtaining the premium dollars that can help the health system maximize how it serves its plan members.

In an FFS model, healthcare delivery systems must consistently deliver high volumes of transactional care to drive financial results. If a health system is paid on a more global basis – from health plan premiums – it can pivot to a panel or population health management approach, addressing essential questions such as:

- What will it take to keep people healthy, using the right levels of service, in the right settings, with the right types of providers?

- How do we help steer people to urgent or primary care when appropriate, instead of having them go to the emergency department?

- How do we help patients understand that seeing a physician’s assistant may be a better choice than a physician, depending on their need?

With revenue from monthly premiums, a health system has a steady funding source to do things differently, keeping step with the U.S. healthcare system’s shift to focusing on the health outcomes of a panel of patients.

To fully understand the significance of assuming full risk, it’s important to recognize there are various types of risk, including the following.

Insurance risk. A health system might take on risk it doesn’t understand that might lead to adverse financial outcomes. Today, this risk is mitigated somewhat by risk adjustment, but it was a bigger concern for health systems a decade ago.

Performance risk. There is a risk that a health system’s infrastructure and culture cannot produce positive results in this new payment model. When an organization’s whole revenue cycle is built around FFS payment, that’s not a simple or quick thing to change.

Risk of the status quo. If a health system does not evolve, it may be vulnerable to other payer- or provider-backed models that enter its market and begin peeling away its customers. Change is coming to nearly every corner of healthcare, so doing nothing could be the riskiest long-term strategy.

Factors against taking on full risk. Circumstances that could argue against a health system taking on full risk include:

- A lack of the infrastructure the organization would need to support it

- The lack of a market for it, which, while uncommon, may be the case in some markets

- A culture that is wholly committed to FFS, in which case, pivoting to value-based care will not be quick or easy