Lessons learned from the transition from volume to value

Bonnie B. Blanchfield, CPA, ScD

Gregg S. Meyer, MD, MSc

Anjali Thakkar, MD, MBA

Michelle Pai Howell, MPH

Catherine Meyer, MSc

Ten years ago, accountable care organizations (ACOs) were introduced in the Affordable Care Act as a way to promote the Triple Aim of improving the quality of healthcare and the patient experience while lowering healthcare’s cost. This goal was to be achieved through changing payment incentives, where ACOs would be expected to eventually assume downside risk. The willingness to take on such risk was deemed essential to the nation’s efforts to transition from volume-based payment (fee for service [FFS]) to value-based payment (ACO and/or capitation).

Yet many ACOs have been reluctant to take this step. Pre-COVID-19 national surveys indicate that the majority of current ACO participants would leave the program if they were required to assume downside risk, and many feel they need three or more years to prepare for it. If ACOs are to continue to effectively lead the transition to value, they must fully grasp all the success factors that will determine future success, including success with downside risk.

To gain insight into these factors, we reviewed findings of national surveys of ACOs that provided perspectives of CFOs and other senior executives, and we explored key organizational, financial, market and other characteristics leading to the decision to take on risk at five geographically diverse organizations that were participants in the CMS Pioneer ACO program

Preliminary observations

Our initial research pointed to limited understanding among hospitals and health systems on how to successfully navigate the challenges of the volume-to-value transition (VVT).

Some factors that play an important role in the decision are well known, including:

- Strong leadership vision

- Long-term organizational commitment (as opposed to short-term shifting commitments)

- Upfront resource investment

- Ability to carefully design stakeholder incentives

What is limited, however, is understanding of the financial and organizational characteristics an organization must have to remain committed to the VVT for long-term success.

Many healthcare organizations have found themselves stuck in the middle of the VVT trying to manage operations under two often-competing financial models. Financial leaders are looking at the bottom line, focusing on margins and maintaining profitability in income statements while keeping cash on the balance sheet. Meanwhile, population health management and clinical leaders are looking to improve and redesign healthcare delivery while maintaining quality, with hopes patient populations utilize less care and less expensive services, These opposing interests create constant tension between finance teams balancing the budget and innovation/population health teams trying to deliver coordinated, high-quality care.

We observed that many organizations begin the VVT with a Medicare shared savings program and, if successful, take on additional value-based contracts with other payers. We therefore focused on the factors that led to Medicare ACO participation (specifically the Pioneer ACO program) and how those influenced VVT success, both in financial contract performance and continued participation and expansion in ACO and risk arrangements.

Findings

Our study tested two hypotheses:

- Senior finance leaders are primary drivers of decisions to enter into ACO contracts

- To succeed with ACO contracts, hospitals and health systems must first have the following elements in place:

- The ability to invest financially in population health

- Adequate cash reserves on their balance sheets

- Demonstrated multiple years of profitability

- Elastic demand for services with commercial backfill

The research disclosed that the first of these hypotheses is correct. Without exception, none of the study participants entered into an ACO without strong endorsement by the CFO.

We also found that no single set of criteria informed every organization’s decision to participate in the VVT. Each organization brought its own history, capabilities, infrastructural readiness, market characteristics, strengths and weaknesses into the final decision process.

Nonetheless, we did find common themes that to various degrees appear to support organizations’ plans regarding the VVT. The following themes were shared by two or more participants.

Organizational history. The organization’s prior experience is clearly an important driver of decisions. Several participants had either previous or ongoing experience with risk (e.g., history of owning a health plan) that made them more comfortable with both the risk and rewards of participation. This finding suggests that the transition is likely to start where there is existing risk. It also suggests regions where there has been limited assumption of risk (e.g., the South-East) are likely to see the VVT proceed more slowly because of a lack of either significant incentives or entry of disruptive actors such as integrated payer-provider organizations that have risk experience. The impact of COVID-19 and an organization’s history in managing it will be an important factor to follow in the coming months and year.

Regional influences. We found that organizations that were considering participation in value-base contracts were more likely to move forward if other organizations in their region also were participating. This finding partially explains the clustering of Pioneer ACOs in Eastern Massachusetts and Minnesota.

Good will. A consistent sense of good will in organizations toward participation was independently cited in all our interviews. This result suggests organization wide readiness and willingness to participate are more important than other capabilities (e.g., an enterprise electronic health record [EHR]) that we expected would be driving factors.

Synergies with other organizational activities. The ability to use the VVT to address other issues was consistently cited as a driver of participation. For instance, some saw the VVT as an opportunity to free up existing strained capacity, both inpatient and outpatient, in an environment of elastic demand, creating backfill opportunities. Beds, procedures or appointments vacated by patients who were now well managed under risk-based contracts could be used for new patients, presenting a potentially more favorable payer mix. Others saw ACO participation as an opportunity to learn and apply insights from risk contracts to their own insurance products. Yet another synergy was in the use of risk contracts to create incentives, either financial or reputational, for community physicians to become employed or affiliated.

Preparatory investments in infrastructure. We also found that, without exception, participants had made at least some investments in critical VVT-enabling infrastructure, including electronic data warehouses and EHRs. These investments were necessary, but they were not specifically intended to support a decision to participate in the VVT. Indeed, no organization cited its investments in infrastructure as a reason for participating in an ACO, nor did any organization state that its investment in infrastructure was intended as a precursor to such a plan.

Financial strength. Surprisingly, this factor was not considered to be as important as we originally expected. Although some organizations had strong balance sheets and a potential pool of risk-based capital, this was not true for others. In fact, some of the organizations noted that they had very little to invest in population health management (PHM) programs and hoped that success in the VVT would create new resources for investment.

A model for the VVT

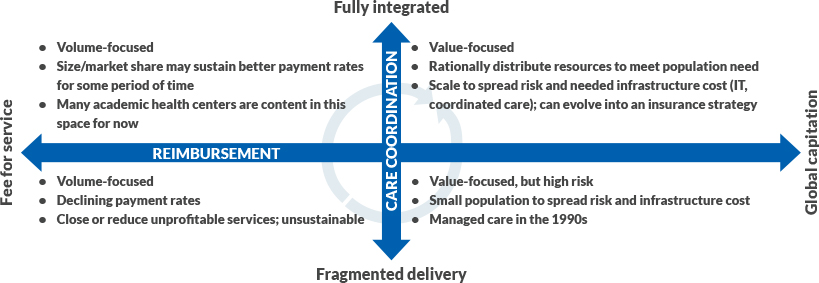

The study’s five case studies (see the sidebar summarizing case studies) provide information for providers that have not yet initiated the VVT, particularly those re-evaluating their risk position post-COVID-19. They provide insights to allow risk-averse healthcare organizations to better assess their readiness for the VVT. Our observations from these case studies are summarized in the conceptual model depicted in the exhibit below.

Potential pathways from volume to value

Source: Gregg S. Meyer, MD, MSc, 2020

In this model, all organizations begin in the lower left quadrant (fragmented care under FFS payment) while considering the move to the upper right quadrant (integrated care under a capitation or other risk arrangement). It is clear from published studies and our findings that an organization cannot rapidly or successfully move immediately from the lower left to upper right quadrant. A transitional state is required.

We found that some of the participating organizations chose to take the “Northwest Passage” (i.e., moving from the lower left to the upper right quadrant through the upper left quadrant). These organizations have sufficient resources and have made significant investments in infrastructure (e.g., PHM programs), yet they do not immediately assume sufficient risk to make those investments payoff. They are likely to undergo a period of financial loss, particularly in the early years of the ACO, because their infrastructure investments are made while they still are under largely FFS payment, which leaves limited opportunity for creating savings to justify their investments (because the savings accrue to payers rather than providers making the investments). With the right investments in integration and strong execution, they could be expected to seek greater risk and make a stronger commitment to a value-based strategy so their investments will yield a return.

We found that other organizations are taking the “Southeast Passage” (i.e., moving from the lower left to the upper right quadrant through the lower right quadrant). These organizations have a history of taking risk (often through their own insurance plans), and they engage in the ACO model in the hope that success will free up resources to make future investments in infrastructure. They, too, are at risk for a period of financial loss because the organization is taking risk (with the attendant cyclical success in gaining savings) without sufficient integration to ensure success.

Policy implications for the VVT

Payment reform efforts should be cognizant of the costs of the volume-to-value transition (VVT) and facilitate “safe passage” through both routes described in the main body of the article. Whether an organization traveled the “Northwest” or “Southeast” route represented in the exhibit above is largely a product of their history (their degree of comfort with risk through earlier experiences) and their finances (whether they have resources to invest in integrating infrastructure and risk-based capital to cover losses).

In either case, CMS and other payers should consider structural and policy elements for future value-based payment programs to support the VVT.

One clear step is to address the period of potential early losses to ensure that organizations sustain their commitment to the VVT. The willingness of organizations to sustain such losses has surely been altered by COVID-19.

For those without resources to invest in integration infrastructure, which constitute many more organizations than previously in the wake of COVID-19, support such as the delivery system reform incentive payments in Medicaid risk programs, which is at risk in later years of the contract, could ease them through the “Southeast Passage.”

For organizations taking the “Northwest Passage,” minimizing down-side risk during the initial years of ACO participation (as in the Medicare Shared-Savings Programs) could help shield them from financial shocks as they are waiting for their investments in population health management and infrastructure to yield savings.

Regardless of the path taken, all organizations noted the importance of good will and a desire to be seen as proactive in solving healthcare’s challenges by committing to the VVT. The uncertainty of mid-course programmatic changes, moving goal posts and altered methodology by payers is likely to considerably erode su good will.

The need for a new perspective for value-based payment programs

In recent months, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused many organizations to re-evaluate their approach to the volume-to-value transition (VVT). Healthcare providers that were in a purely fee-for-service (FFS) environment saw their revenues collapse as elective services were shut down and patients avoided them due to fear of infection. But providers that were further along in the transition saw at least some of their revenues preserved through capitated payments for those in premium-based risk or the promise of shared savings in the future due to lower utilization. Although some of those clinging to FFS may be anxious to “ramp back up” to their new normal, many will re-examine whether they should be taking greater risk focused on value and asking whether they are ready for it.

The decision to participate in the VVT is multidimensional, sensitive to context and driven by a few key executives, especially the CFO. COVID-19 has introduced an additional element that will prompt many organizations to evaluate the pacing of this transition. Future design of ACO arrangements taking these factors into account could encourage a wider range of organizations to engage in the VVT.

The finding that the CFO is a key decision-maker in the VVT suggests that future evaluations to inform policy should take a more financial (e.g., focus on ROI) than economic (e.g., bending the cost curve) approach. Studies of whether a program changed the trajectory of costs at a national level are unlikely to shift the opinion of ultimate decisionmakers as much as a practical assessment of whether the investments and/or risk had an impact on the organization’s finances. The financial challenges wrought by COVID-19 are likely to result in a greater appeal of value-based payment, but healthcare organizations must temper that desire with a frank appraisal of their readiness, which they can assessthrough the framework we propose here.

The research for this article was supported by The Commonwealth Fund Health Care Delivery System Reform Small Grants Fund.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the senior executives from the five participating organizations for their willingness to candidly share their motivations and experience. We also would like to thank the Commonwealth Fund of New York, New York, for its support of this work, and Melinda Abrams, Tanya Shah and Mekdes Tsega from the Fund’s Delivery System Reform program for their advice and guidance.

5 case studies of decision-making in the Pioneer ACO program

Our research into how healthcare organizations have approached the volume-to-value transition (VVT) included case studies of the following five organizations. Here is a summary of key case study findings.

Case 1: Integrated delivery system

Payer mix: 85% public payers

2017 bond rating (S&P): BBB

Expectations: Improve ability to get as far upstream on premium dollar as possible.

Motivation: Fits with overall system strategy of focusing on managing population health, controlling growth in costs, tracking outcomes and steering patients to the health system.

Market influence: Highly competitive market, but other local providers are not interested in the organization’s mix.

Focus on backfill: Capturing more lives and decreasing leakage rather than backfill were key drivers.

Investment: Little incremental investment was required because prior infrastructure (developed over the prior 20 years) from Medicaid capitation could be leveraged.

Lessons learned: Having an electronic data warehouse, leveraging existing infrastructure (and spreading fixed cost) and building on past risk experience were essential.

Case 2: Multispecialty group practice

Payer mix: 56% public payers

2017 bond rating (S&P): A

Expectations: Strengthen presence in region with growth in lives and providers to prepare for future with more risk.

Motivation: Opportunity to build on experience with full capitation in commercial market and prior successful Medicare demonstration.

Market influence: Fragmented FFS market provided an opportunity to be differentiated among potential provider groups.

Focus on backfill: There was a lack of backfill opportunity in region, so loss of volume for local hospitals was a real concern and limited the practice’s participation in the model.

Investment: Little incremental investment required because prior infrastructure from commercial capitation could be leveraged (particularly analytics).

Lessons learned: The lack of any risk-based capital made it impossible to remain in the program if the practice incurred losses; reserves are now booked for potential losses.

Case 3: Integrated delivery system

Payer mix: 41% public payers

2017 bond rating (S&P): AA-![]()

Expectations: The emphasis was more on learning more than on revenue generation. The organization recognized that losing money on risk-based contracts might be offset by gains in FFS revenue.

Motivation: To gain experience with downside risk and managing the Medicare population.

Market influence: There was a belief that FFS status quo was not sustainable in the market.

Focus on backfill: Elasticity of demand for backfill was not present in the short-term and was not part of the decision.

Investment: The organization built out a care management team, which also was used to manage other risk-based contracts.

Lessons learned: Lack of alignment of incentives between system and providers and limited risk led to less ambitious goal setting.

Case 4: Multispecialty group practice

Payer mix: 30% public payers

2017 bond rating (S&P): BBB-

Expectations: “Spill over to Medicare Advantage (MA)” hypothesis that learnings from participating as a Pioneer ACO would improve their risk performance in other products.

Motivation: The program was aligned with the organization’s history, with the objective of ensuring contracts would “catching up” to previous performance levels.

Market influence: The presence of other ACOs in the region made this undertaking compelling.

Focus on backfill: Not applicable in a physician-based ACO.

Investment: Leveraged existing infrastructure such as electronic health record and MA data, which proved essential.

Lessons learned: Pioneer participation had a carry-over benefit in lessons learned for the MA business (particularly for post-acute care utilization, care coordination and high-risk management), and it enabled the organization to focus on quality.

Case 5: Integrated delivery system

Payer mix: 54% public payers

2017 bond rating (S&P): AA-

Expectations: Gaining experience with risk while generating shared savings to offset population health management investment.

Motivation: To gain experience with downside risk and managing the Medicare population, with the hope that it could lead to future success with greater risk (e.g., MA).

Market influence: Other regional Pioneer participants were motivating but not drivers of participation decision.

Backfill: Ability to backfill with elastic demand for hospital services was essential to selling the program internally.

Investment: Availability of sufficient reserves to cover potential losses was important.

Lessons learned: Incentivizing physicians and changing behavior of specialists is cs discussion.