HEALTHCARE 2030: HEALTH vs. CARE

If you’re resisting wellness models, prepare to be left behind

By Lisa Eramo, HFMA Contributing Writer

Laura Kaiser is on a mission to help people live healthy lives. As president and CEO of SSM Health, Kaiser is moving the St. Louis-based Catholic health system toward an approach that promotes health instead of healthcare, and prevention instead of treatment.

For SSM Health, that goal entails such things as creating frequent touchpoints with patients who have one or more complex chronic conditions.

“The majority of the population has at least one chronic condition, and that number is increasing,” Kaiser said. “Our goal is to help people with chronic conditions manage their health to the best of our collective ability.”

That tack is very different from the old but still-in-use approach of trying to keep heads in beds and the revenue flowing. Kaiser shares with many health system leaders a growing belief that to remain relevant in the years ahead, health systems must take a holistic view of health — one that goes beyond just helping people when they’re sick.

“Acute care will always have a place in this spectrum, but the definition of health is far broader,” Kaiser said.

Similarly, Sandro Galea, MD, PhD, dean and Robert A. Knox professor at Boston University School of Public Health, said, “What we call health is not health. It’s medicine.”

“All of us in healthcare have a responsibility to do what we can to make people healthier,” he said. “Every CFO needs to say, ‘What am I doing to contribute to that? How do I fix it? How do I actually become part of an enterprise that generates health rather than simply promoting cure?’”

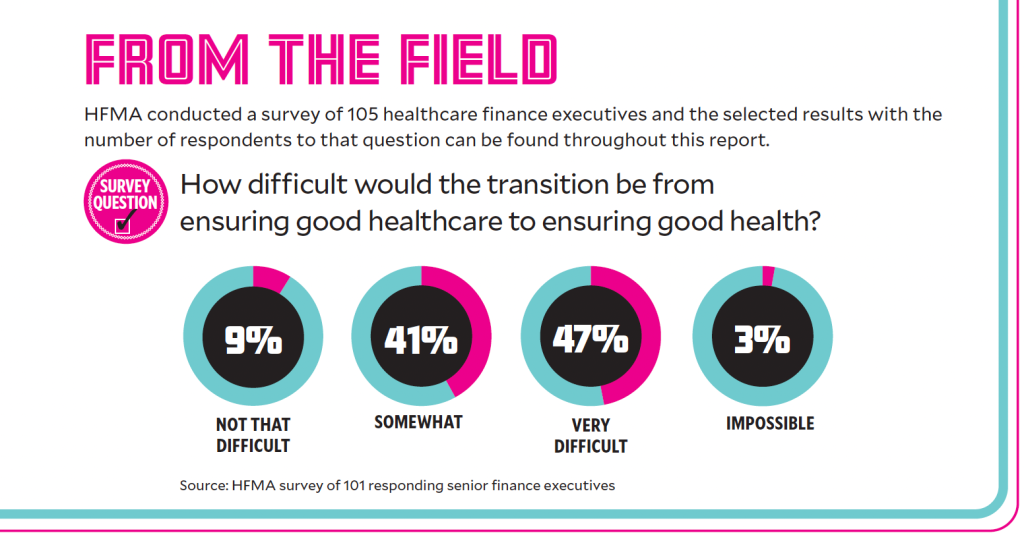

But getting to a place where health is the expected outcome is going to be a challenge. An HFMA survey of healthcare finance executives found that 88% of respondents expected it to be somewhat or very difficult to transition to a wellness approach, while 3% expected it to be impossible.

health is not health.

It’s medicine.”

— Sandro Galea, MD, PhD, dean and Robert A. Knox professor at Boston University School of Public Health

Some respondents sounded pessimistic about the prospects for a health-first approach, including one who wrote: “We have tried to do this for many years. Some people are very focused on their health. The vast majority do not think about healthcare until they have a health issue. Even with healthy living, what we likely will see is simply deferral of the costs — a great objective but likely a fool’s errand.”

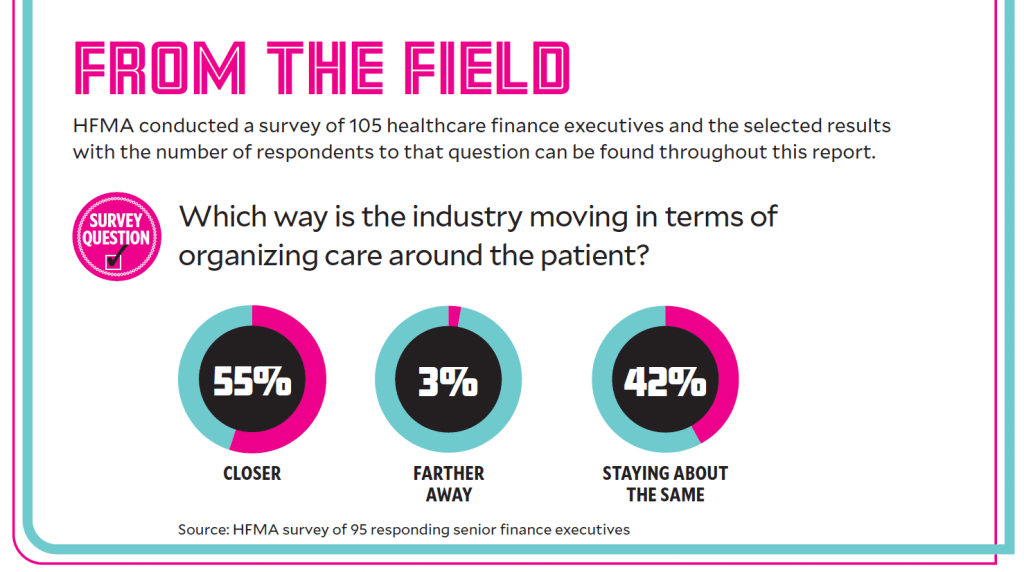

Nonetheless, there still is considerable support for the concept, with providers moving in that direction in both broad and narrow strategies. Those include increasing the focus on patient care management and primary care, partnering with health plans on value-based care models and getting people on board with healthy living earlier in their lives.

Focused care management

At SSM Health, a whole-patient strategy is centered around care management and a virtual care center that’s open seven days a week, 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.

“The idea is to partner with patients,” said Kaiser. “If you have a strong care management system from stem to stern, patients and families can partner with their care team and won’t get lost.”

Kaiser looks to the next decade and beyond with a focus on sustainability, something she suspects will require three things: cost-effective care, workforce efficiency and healthier patients. If health systems are to remain relevant, Kaiser said, they need to take a holistic view of health — one that goes beyond just helping people when they’re sick.

For example, SSM Health identifies and addresses social determinants of health (SDoH) through what Kaiser described as groundbreaking work with its electronic health record (EHR) vendor to call up and record recoverable SDoH data at the point of care. The health system also continues to develop partnerships with community agencies to address barriers to care and has taken on full risk for more than 700,000 patients in the past six years.

“We want to help people stay well,” said Kaiser. “If we can do this, the total cost of care for patients and society will decrease.”

Promoting holistic primary care

In the decade ahead, experts say providers will need to re-evaluate their role in keeping people healthy. In many cases, this may require going back to the basics, which means primary care, said Kameron Matthews, MD, JD, FAAFP, chief health officer at Cityblock Health, based in New York. Cityblock is an integrated primary care practice for Medicaid and dual-eligible populations where patients receive primary care, behavioral health, social care and nontraditional services all under one roof.

— Kameron Matthews, MD, JD, FAAFP, chief health officer Cityblock Health

“We’re trying to address patients’ needs holistically and remove barriers to care,” said Matthews.

Cityblock Health assumes full risk in most payer contracts, but Matthews said it’s actually easier that way.

“Our patients require many different kinds of services,” she said. “The restrictive nature of the finance system under a fee-for-service model prevents us from offering those services.”

She provides the example of an addiction specialist or behavioral health specialist who meets with a patient during their annual physical.

“We’re not worried about what it looks like on a bill,” she added.

In addition, Cityblock often refers patients for complementary and integrative health services like reiki, tai chi, meditation and acupuncture for pain and stress management. It also has a strong clinical pharmacy program aimed at helping educate consumers about their medications and promote medication adherence.

“It’s the health system’s responsibility to incentivize good health and well-being as opposed to disease treatment,” said Matthews. “We need to upend the model, and a value-based system is the way to go.”

A commitment to risk

— Patrick Holland, CFO, Atrius Health

Atrius Health, which operates 31 medical clinics in eastern Massachusetts and is part of Optum, gets roughly 80% of its patient-service revenue through value-based contracts, and it wants more.

“We’re all in,” said Patrick Holland, Atrius’ CFO. “Risk contracts are fundamental to our business model, and we seek out risk every chance we get.”

Atrius, which was acquired by Optum in 2022, participates in federal programs — the Medicare Shared Savings Program and Primary Care First — but 66% of its patients attributed to risk-based contracts are commercially insured.

To increase its full-risk business, Atrius negotiated a contract with the state’s largest payer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, in which it takes 100% risk on its preferred provider organization (PPO) members as well as its health maintenance organization (HMO) members.

Building off its success there, the organization negotiated a similar contract with Optum’s parent UnitedHealthcare in 2019.

“And then we hope to use that as a model to get other national payers into risk-based contracts,” Holland said.

Atrius’ comfort with value-based contracts reflects Massachusetts’ long history of encouraging health plans to transfer risk to providers, which dates to the early 2000s. The state publishes annual reports tracking this transfer, which puts pressure on health plans to get on board.

“Despite how much a provider may want to take on risk through value-based care contracts, it’s the payers that have to be willing and able to engage in that discussion,” Holland said.

Because of the scale of its risk-based business, Atrius has been able to invest in considerable infrastructure to support value-based care.

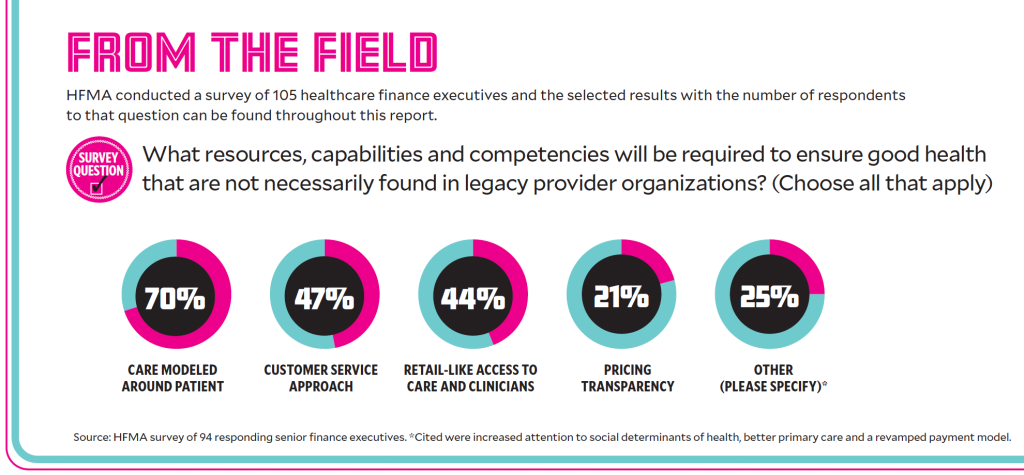

“We have a fairly robust centralized structure that includes a population health department and clinical pharmacists that help us manage the pharmacy spend under the risk-based models,” he said. “We have a quality and safety department and a clinical informatics and analytics department led by a data scientist and an MD.”

But Holland said all of those components are not essential for organizations that are just starting with value-based care.

“If you are just getting into the risk game in some part of the country where it’s not really common yet, I would focus on a strong case management department that can do outreach to patients, can manage the transitions of care, identify and start to manage the high-risk chronic disease patients,” he said.

Dogged in its approach

Allina Health, the market leader in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, jumped into value-based care early, participating in two of CMS’s early accountable care organization models a decade ago. It also formed a joint venture with Aetna to share financial risk. They didn’t work as planned, but in 2019, its board and leadership team recommitted to the value concept.

— Ric Magnuson, executive vice president and CFO, Allina Health

“That’s when we began a pretty significant push back in the value-based world,” said Ric Magnuson, executive vice president and CFO of the 10-hospital system.

Although it’s still early going, Allina benefits from having its largest payer— Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota (BCBSMN) — committed to value-based payments. In early 2020, Allina signed a five-year contract to partner with BCBSMN; that is one of the insurer’s 28 value-based arrangements across the state. Together, those arrangements account for more than 65% of its total medical spend.

“We expect this strong value-based arrangement penetration in Minnesota to continue growing,” Eric Hoag, BCBSMN’s vice president of provider relations, said in written remarks. “We feel that our value-based arrangements — especially in our newest version in which we’ve moved to true downside risk agreements — are overall net positive for our members.”

Allina’s contract with BCBSMN calls for the health system to assume greater downside risk over time. It also receives a population health payment to support the move away from fee-for-service. The COVID pandemic derailed progress, prompting the contract to be extended to seven years.

Allina has a value-based contract with another payer and aspires to add more in the future.

“We believe it’s the right thing to do for the community, but managing populations in healthcare is not easy,” Magnuson said. “You have to have the stomach for a long view.”

Engaging a consulting firm to assess its capabilities for population-level management was critical.

“If you’re a pure provider organization, you most likely do not have the mindset or the capabilities in your organization, and you’re going to need a partner to help with this, at least in the beginning,” he said.

A clinical team led by Allina’s chief medical officer is working on the new care models needed to succeed in value-based payments, with support from Magnuson’s payer relations team. An ongoing challenge is getting the necessary data from payers, including patient attribution, claims data and comparisons with benchmarks, from payers.

“We’re maybe 50, 60% of the way there to getting all the information, and we will be getting some new tools this year that we think will help with this,” he said.

Primary care: What can be learned from outside the U.S.

Atul Gawande, MD, author and former head of the now-shuttered healthcare disruption agent Haven Healthcare, is the assistant administrator for global health at the United States Agency for International Development. He said other countries offer insights that could be applied in the United States.

He recently returned from Indonesia and Costa Rica, countries where life expectancy was increasing, while in the United States it has stalled out. In Indonesia, life expectancy at birth grew to 71.3 years as of 2019 from 67.2 years in 2000, while for the same periods Costa Rica’s life expectancy reached 80.8 years, up from 78 years, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In the United States, life expectancy grew to 78.6 years from 76.7 between 2000 and 2010, and was essentially fl at through 2019, according to WHO. Life expectancy in the U.S. then fell to 76.1 by 2021, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With much smaller Costa Rica outperforming our nation, Gawande said the lesson is that it’s not about how much is spent — it’s where that spending occurs.

“The core of it is investing in community-based primary healthcare,” said Gawande. “However, primary care isn’t only about having first-line providers available in their offices to see people when they come in. The value is created when you have a team of people who can do outreach and ensure people don’t fall through the cracks. “Contrast this with the way we provide care in the United States” he said. “We rely on people showing up when in reality, a large portion of our population has limited contact with primary care.”

Longer-term readiness also is a weak spot. “What I’ve come to realize is that disruption is increasing due to climate change, conflicts and outbreaks around the world,” said Gawande. “Very few health systems are prepared for recurrent disruption.”

Hospital CFOs must invest in core teams of people who know how to promote health and wellness during emergencies such as war, natural disasters and more, he said.

“Much of health and healthcare planning is about planning in months and delivering over years,” he said. “But you also need people who can plan in days and deliver in days. These are a different breed of people.”

Promoting children’s health

At Jacksonville, Florida-based Nemours Children’s Health, the prescription for fixing healthcare in the United States is simple: Understand health, pay for health and start with children.

“Nemours is in the business of creating health,” said R. Lawrence Moss, MD, the organization’s president and CEO. “I believe this equation starts with children and works best in children. The role of children’s hospitals should be the stewards of childhood health — not only the deliverers of medical care.”

Why start with children?

“The way to ultimately influence disease throughout the lifespan is to make changes in childhood,” Moss said. “Taking steps to improve the health of children has an enormously powerful impact. If we really want to influence disease burden in our society, we need to start with children.”

It also starts with screening for SDoH, he said.

— R. Lawrence Moss. president and CEO. Nemours Children’s Health

“Healthcare organizations can be the convener that brings disparate community organizations together to focus on children’s health,” Moss said.

However, Moss admitted that even heading into the next decade there are challenges, namely that most current financial incentives are counter to the creation of health.

“Right now, when Nemours or any other health system makes investments in food security, safety or safe housing, those are negatives to our bottom line,” he said. “The minute we get paid for health, it’s a win for patients and their families, and it’s also a win for the sustainability of our organization.”

Flipping the financial narrative requires organizations to advocate for changes in health policy, Moss stressed. For example, Nemours played a critical role in creating the Caring for Social Determinants Act that lays out a road map for whole person care.

“This act won’t cause an immediate change in payment systems, but it’s an important step,” Moss said. “We’re working at both the state and federal levels on a number of pieces of legislation to accelerate this change.”

Nemours is also working with state governments in five different states to perform pilot programs to demonstrate the value of whole-person care.

“We’re trying to develop aggressive contractual relationships that are value based with upside and downside risk,” Moss said. “We’re pushing all of our payers in this direction. We’re also looking at large groups of patients — both federally and commercially insured — for whom we could take full accountability and risk. Nemours is prepared to take on considerable risk in large populations. We believe we have the infrastructure and ability to do this successfully.”

Nemours’ effort goes back to its value-based services organization (VBSO), launched in 2017 and led by a chief health equity officer, chief population health officer and chief value officer. The VBSO includes teams devoted to population health and care management and coordination through collaboration between Nemours specialists and independent physicians in the community.

The nearly $70 million investment in the VBSO is without financial return, Moss said.

“We’ve used our resources to make this investment because we think it’s the right thing to do,” he said. “In a fee-for-service environment, not only does the VBSO cost us money, all of the better health it produces also costs us money because patients require less medical care. However, we’re willing to make that investment because we think we’re on a path to a better system. We’re willing to get out in front to be a pioneer.”

A post-COVID consideration: Communicating science information to the community

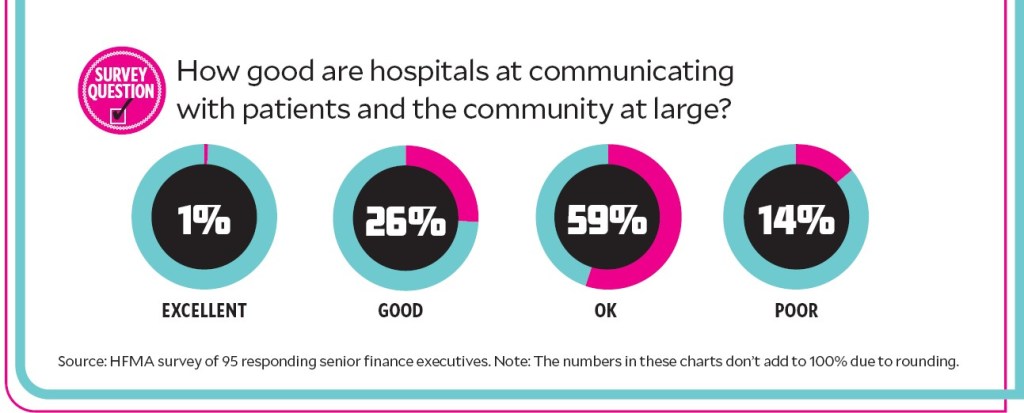

There’s a growing need for healthcare organizations to hire chief medical communications officers who can translate science to the public more broadly. Getting patients on board with a health-focused approach could be a challenge as more health systems move toward health-first care.

And it’s evident healthcare organizations may need to regain public trust that was lost during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Jayne Morgan, MD, executive director of health and community education at the Piedmont Healthcare Corporation.

“If COVID taught us anything, it’s that if we don’t step up and educate patients, someone else will — and the information may cause of lot of damage,” said Morgan, who is responsible for internal and external medical communications at Piedmont.

Morgan frequently hosts virtual events on health-related topics, speaks with media outlets, writes articles for Piedmont’s internal magazine, and works with the hospital’s brand and growth development division to identify other ways to educate patients.

“It’s time for large hospital systems that serve a big demographic to have someone in this role,” she added. “That person can provide accurate information and deliver it in a consistent way. They can be a trusted resource for the community.”