How to manage risk-based payment in the era of the global pandemic

Thomas Persichetti, FCA, ASA, MAAA, consulting actuary and president, Persichetti & Associates LLC.

To succeed with risk-based contracts through the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, healthcare organizations require analytic capabilities for modeling the revenue impact of the crisis through all its phases.

Healthcare finance leaders are coping with significant revenue losses in the second quarter of 2020. And it is unlikely they will see a quick return to prior volumes and revenues. Facing such an uncertain future, many finance leaders whose organizations participate in value-based or alternative payment models (APMs) may hold out hope that the APMs could be a means to recapture lost revenues.

But the reality is that payouts in these programs could be limited by some of their design features, as well as by increased unemployment. Finance leaders therefore need to be able to assess key risks associated with alternative payment models (APMs) to understand the impacts from the pandemic on risk-based contracts at key phases in its progression.

Phases leading to a post-pandemic new normal revenue model

When this article was being prepared for publication, all 50 states had started some level of a phased approach to re-opening. As stay-at-home orders are lifted and non-essential businesses open, some expect that there could be a second wave infection. This discussion, however, works from three assumptions:

- That any potential secondary wave infections will be localized

- That the federal government will not issue additional mandatory closures on a national level

- That unemployment will have a negative impact on payer mix

The revenue impact of the COVID-19 crisis on provider organizations can be understood as unfolding in five phases:

- Pre-pandemic, with baseline volumes prior to pandemic and predictable seasonal patterns

- Service deferral, where stay-at-home orders are in effect and volumes and revenues are down significantly

- Transition, where business gradually reopens, with phased-in surgical services

- Surge, where the healthcare system becomes fully operational and volumes increase as a result of pent-up demand

- New normal, where providers operate in a new steady-state condition

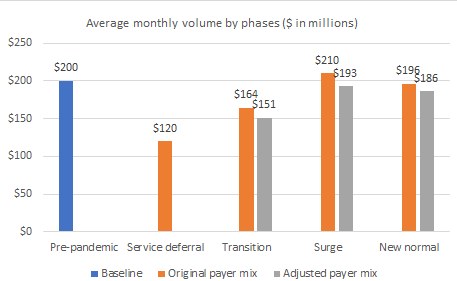

The exhibit below provides a sample analysis of the revenue changes over these five phases for a $2.4 billion system, with and without payer mix changes.

5 phases of revenue changes for a health system with 2.4 billion in revenues, with and without payer mix changes

Source: Persichetti & Associates LLC, 2020

The values shown here reflect the following assumptions for modeling purposes:

- Monthly revenue will decline substantially during the service-deferral phase because of the reduction in payment for services covered by commercial insurance.

- Revenue will see a partial return as the nation enters the recovery phase, but there is a possibility that some commercially insured services will not return.

- As the nation’s confidence builds, there will be a surge in elective services, but monthly revenue may still fall short of historical levels due to the loss of some commercially insured services.

- After the brief surge, revenue levels will settle into a new normal, which will likely by lower than pre-pandemic levels.

Requirements for effective modeling

Annual 2020 expenditures will depend on the length of each phase and the average revenue relative to the pre-pandemic baseline. There is no prior experience of a global pandemic recovery to inform assumptions for the model. The most appropriate thing we can do is use first principles in making assumptions.

A well-constructed modeling process must leverage known information, be specific about the problem, document the assumptions and continue to monitor the emerging experience. A generalized model may forecast total volumes and revenues. A more specific approach would be to segment the components such as inpatient/outpatient, surgical/non-surgical and payer class.

For APMs, the specific challenges are:

- Identifying the revenue opportunities available in 2020

- Determining how to mitigate risks of not realizing that revenue

- Developing a framework to evaluate opportunities for 2021

The exhibit below models the revenue impact of payer mix changes through the five phases, and it exemplifies how differences in phase lengths and average relative revenues can impact revenues for a sample health system with average annual revenue of $2.4 billion.

Case example: Annual hospital revenue impact from different phases of the COVID-19 crisis on a health system with $2.4 billion in revenues*

| Phase length in months | Average monthly revenue per phases* | Percentage of baseline revenue | Total revenue per phase* | |

| Pre-pandemic | 2.5 | $200 | $500 | |

| Service deferral | 2 | $120 | 60% | $240 |

| Transition | 1.5 | $164 | 82% | $246 |

| Surge | 2 | $210 | 105% | $420 |

| New normal | 4 | $196 | 98% | $784 |

| Total revenue | $2,190 | |||

| Percentage change from $2.4 billion | -8.8% |

*Dollars in millions

Requirements for modeling the impact on total cost of care

To develop a composite estimate of the impact on the total cost of care, the same type of modeling is needed for physician, ancillary services and prescription drug expenditures. Health systems can supplement facility data with data for their employed physician group and their own employee health plan experience to provide inputs for nonhospital services. These results can be combined with the service expense allocation among these categories to develop a composite impact estimate.

The exhibit below shows how the estimated reduction in care derived from the five-phase model might be applied to a total-cost-of-care APM for 2020 experience.

How to apply an organization’s estimated reduction in care from COVID-19 to a total-cost-of-care advance payment model for 2020*

Expense allocation |

|||

Service |

Reduction |

No prescription drugs |

With prescription drugs |

| Hospital |

-8.8% |

56.6% |

47.0% |

| Professional |

-6.0% |

38.6% |

32.0% |

| Ancillary |

-2.0% |

4.8% |

4.0% |

| Prescription drug |

0.0% |

– |

17.0% |

| Net impact |

– |

-7.4% |

-6.1% |

Source: Persichetti & Associates LLC, 2020

The values shown here reflect the following assumptions for modeling purposes:

- An organization will be able to estimate the COVID-19 reduction using empirical data.

- Expense allocations for a category represent the payments as a percentage of total payments which count towards the financial perfomance. Expense allocation sums to 100%.

- Expense allocations can be estimated based on payer eporting in prior years. For example, accountable care organization expense allocations can be estimated using the quarterly expenditure/utilization report.

The financial benchmark target

The most important component of any APM with respect to performance in 2020 and 2021 is how the financial benchmark target is set. Typically, the trend used in the development of the financial target for APMs is determined in one of three ways:

- Prior experience trended forward with historical trend

- Prior experience trended forward with a fixed-trend rate

- Prior experience trended forward with a market trend factor

The first two models are prospective and will likely produce a target higher than the 2019 experience baseline. In these arrangements, the negative trend for 2020 will produce shared savings. How much savings will depend on contractual elements, such as the following:

- Risk corridors

- Percentage of shared savings

- Reductions for quality performance

- Savings maxiums

The third model is retrospective, where experience is compared with empirically derived market trend rates. These financial targets will be lower than the 2019 baseline. The positive effects of medical management programs that contribute to success in retrospective models could be offset by the external forces introduced by COVID-19.

Member attribution and unemployment

As of May 29, more than 41 million individuals filed new unemployment claims in the United States since the start of the pandemic.[a] Most individuals who have suffered a loss of employer-sponsored coverage will be eligible to enroll in either Medicaid or an Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchange plan, or they will become uninsured.

The biggest impact of unemployment will be on commercial value-based models.

Unemployment will result in fewer attributed members, with the following results:

- Providers will receive lower care coordination fees.

- There will be a lower base of members for settlement of shared savings contracts.

- Providers will receive lower capitation payments where applicable.

Medicaid APMs will have increased enrollment in 2020, but only a fraction of the recently unemployed members will meet eligibility criteria for Medicaid. Many of these individuals also will not meet the qualifying criteria for attribution, so the enrollment impact will be limited.

For example, assume Medicaid enrollment is 10,000 per month, or 120,000 for the year. For 2020, it will likely take most individuals four to six months to qualify for Medicaid with unemployment counting as income. And when they enroll, they still need to go to the primary care physician to qualify as an attributed member. Assume also that we can expect 20% increase in enrollment. But it may take until September for most to actually enroll. So that is an increase of only 2,000 a month for four month, which is only a 6.6% increase relative to the 120,000 enrollment.

Providers should be familiar with their state or regional Medicaid eligibility rules to develop estimates of the increased membership. Employment status will be a minimal factor in Medicare and Medicare Advantage APMs.

Primary areas of impact

The overall slowdown of in-person office visits and the increase of telehealth and virtual healthcare models add additional challenges with member attribution. Three critical areas will be affected.

1. Member retention. Member retention is a challenge that involves competing forces. On one hand, if telehealth services are excluded from the member assignment algorithms, qualifying visits be lower and lapse rates will increase. On the other hand, including telehealth services in the member assignment could conflict with traditional in-person office visits in the portion of the assignment algorithm addressing plurality of services and most recent service. Payers likely will recommend amending contracts to include telemedicine services in member assignment. Providers should be diligent in evaluating the positive and negative impacts of such amendments.

2. Risk scoring. The shift in enrollment from traditional commercial products to Medicaid and ACA exchange plans will change the underlying morbidity of these populations. Morbidity risk almost certainly will decrease in the Medicaid and exchange products because individuals from employer group coverage generally have healthier morbidity profiles. An organization that currently participates in APMs in each of these market segments will be able to identify this morbidity change if it has a robust data model and risk scores for every member. It will be important for providers to analyze how the underlying risk of the populations has changed as the look to 2021 and evaluate participation and risk options for APMs across different product segments.

3. Quality metrics. Service deferrals will affect quality scores. Metrics that depend on ambulatory visits, such as cancer screening metrics, will have lower scores in 2020. Most payer contracts have either a quality gate or a sliding scale that ultimately determines the shared savings payout. It is conceivable an organization could qualify for maximum payout and receive nothing by missing quality targets. When this article was being prepared for publication, the major insurers had not issued an opinion on how telemedicine will contribute to quality scoring or whether it might lower qualifying standards to meet quality thresholds.

Footnote

[a] Santhanum, L., “3 charts reveal how COVID-19 unemployment crisis isn’t over,” PBS New Hour, May 29, 2020.

APM risk navigation checklist 2020-21

State and local governments are not universally aligned in how fast to re-open the economy. As long as social distancing is in place, reduced ambulatory visits will continue.

As providers shift focus from the immediate operational concerns caused by the pandemic to the future state of a changed health delivery system, they should broaden their view of APM performance and opportunities. As they manage through 2020 and into 2021, they should work from a checklist of areas requiring detailed analysis, including the following elements:

- Five-phase model

- Market migration of newly uninsured

- Retrospective versus prospective trending

- Member attribution

- Risk adjustment

In this new era of unprecedented uncertainty, healthcare organizations will require robust reporting capabilities that include elements of forecasting and analysis of contingent events The highest-performing organizations already have such capabilities to leverage data and analytics in making informed decisions. Yet most organizations will find their existing reporting capabilities stretched well beyond their existing competencies. At a minimum, to succeed in this environment, organizations will require actuarial modeling to evaluate their risk exposure and a process for monitoring emerging trends in unemployment and revenue to ensure they take appropriate actions with respect to APMs.

Outlook and Strategies for 2021

As health systems develop strategies for 2021, they should focus on three areas: trend setting in contract negotiations, impacts of the crisis on attribution methodology and risk adjustment.

1. Contract negotiation. As models move into the 2021 performance year, it is highly likely that contract metric trends will be much higher than historical norms. For example, using a 3% annual trend and a $1,000 2019 cost, the forecasted 2020 and 2021 costs would be $1,030 and $1,061. The pandemic interruption might produce a $926 (-7.4%) cost in 2020. A reset to the original expected cost of $1,061 would produce a 14.7% trend.

Providers should review the formulas used to establish trends. Retrospective models based on market averages will insulate the risk associated with the higher trends. Continuing from the example above, retrospective trends may include a comparison to market averages, and the entire market should experience high trends in 2021. With negotiations around prospective models, it will likely be necessary to eliminate 2020 as a basis for trend development.

2. Attribution methodology. The unemployment rate likely will be lower by the end of the year, although it will still fall short of the pre-pandemic level. Re-capturing attributed members may present an opportunity or pose a risk depending on the extent that telemedicine influences the future healthcare delivery system and any organization’s market penetration. A surge of newly attributed members due to improved employment could have a negative impact on performance depending on the pent-up demand of the members who are gaining access to health insurance again due to employment.

3. Assessment of risk level. Although trends will likely be higher in 2021 relative to 2020, assuming there is not another large-scale disruptive force, providers may see significant opportunity to consider more risk. Insurance projection models will build in higher margins based on the volatility, and actuaries tend to be more conservative when presented with greater uncertainty. Providers should monitor the requested rate increases for individual and small insurance products filed by the major carriers in their markets. These rate increases need to be filed much earlier than the timeline to negotiate contracts.