Healthcare organizations need a better way to measure ROI of health equity investments

Virtually everyone agrees that eliminating disparities in health outcomes would bring vast benefits in terms of lower healthcare costs, longer and healthier lives and increased productivity and living standards. Yet many promising health equity initiatives go unfunded because healthcare organizations cannot demonstrate that they will deliver a positive ROI.

Some health equity advocates suggest that healthcare organizations should set aside considerations of ROI altogether and address health equity out of a sense of social obligation. Although this argument has an undeniable moral appeal, it alone is unlikely to persuade most organizations to make large-scale investments in health equity. There also needs to be a compelling business case for doing so.

Such a business case exists, but it requires looking beyond the standard ROI analysis used by many organizations, which is too focused on the near term and too narrow in scope to capture the full business benefits of investing in health equity. (See the sidebar “Critical limitations of standard ROI analysis” below.)

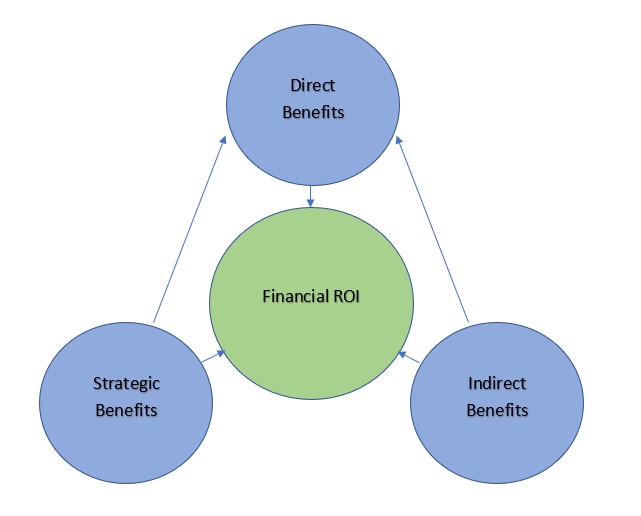

What’s needed is an expanded ROI framework that measures direct financial ROI over a longer time horizon, while also considering the indirect and strategic benefits of a successful health equity investment program.a

Features of an expanded ROI framework

An expanded framework for assessing the ROI of investments in health equity would have three defining features that distinguish it from standard ROI analysis.

1. A longer time horizon for measuring ROI. An expanded ROI framework should measure the direct financial ROI of health equity investments over a time horizon of three to five years instead of the usual one year. Adopting this longer time frame does not mean that healthcare organizations must wait that long to determine whether an initiative is meeting their ROI expectations. Organizations should routinely perform interim reviews to assess whether milestones are being met. But assessing ROI over a longer time frame ensures an initiative would not be ruled out simply because it cannot deliver an immediate return.

2. Indirect benefits of the investment. Beyond the direct impact of health equity investments on healthcare revenues and expenditures, an expanded ROI framework should also consider their indirect benefits. Although such benefits are to some extent qualitative, they can also create positive feedback loops that generate additional financial ROI.

Consider two examples:

- Investing in health equity can enhance an organization’s reputation in underserved communities, thereby improving member and patient retention and growth.

- A healthcare organization’s employees may value its commitment to having a positive social impact, which can help to ensure the organization can meet its hiring and retention goals.

Such benefits are admittedly difficult to quantify. Yet excluding them from ROI analysis may greatly distort financial decision-making.

3. Strategic benefits of the investment. Finally, an expanded ROI framework should take into account the long-term strategic benefits of investing in health equity.

Consider, for example, that America is becoming more diverse, with the U.S. Census Bureau projecting that minorities will constitute a majority of the population within 25 years. The COVID-19 pandemic has also laid bare longstanding health inequities, and both civil society and government are increasingly committed to addressing them. Meanwhile, the healthcare system itself is moving inexorably toward value-based care models, where the potential returns from health equity investments are greater than in fee-for-service payment arrangements.

As these shifts unfold, a commitment to investing in health equity not only will improve future business prospects but also may even be necessary for business survival.

Expanded ROI framework

An approach not without precedent

When assessing the ROI of a health equity initiative, most healthcare organizations would likely see adopting an expanded ROI framework as a major departure from their accustomed practices. The irony, however, is that most organizations already apply an equally broad ROI framework to many other aspects of their business.

Virtually no organization requires its human resources, marketing or legal departments to prove that all their activities generate direct financial ROI, and certainly they are not required to prove their ROI over a one-year time horizon. Yet no one would question that these departments’ activities are essential to long-term business success. So is investing in health equity.

Footnote

a. This column shares results from an ongoing research initiative, “Health Equity Strategies,” which is being conducted by The Terry Group to help healthcare leaders play a more active role in improving health equity across the nation. The authors are sharing results and recommendations from this initiative in a series of columns tailored to the interests of HFMA’s members.

Critical limitations of a standard ROI analysis

Standard ROI analysis has three critical limitations when applied to health equity initiatives.

1. Such an analysis is unable to account for the complexity of the economic, social, and environmental drivers of disparate health outcomes. In clinical trials, where most variables can be controlled for, it is relatively straightforward to isolate the impact of a single intervention, whether it’s a new drug or a new medical procedure. It is more difficult to isolate the impact of introducing a transportation benefit, a mobile health unit or a food-as-medicine program in an underserved community, especially when more than one initiative may be in play at once. It’s a bit like asking, “What did the most to improve my diabetes — the changes I made in my diet, my exercise habits or my medications?” The answer is likely to be all of the above.

2. Even when a standard analysis can demonstrate a positive ROI, that return may not kick in over the one-year time horizon that most healthcare organizations use in budget planning. New initiatives may take time to reach critical mass, individual behavior may take time to change, and trust in the healthcare system may take time to build. No one expects to earn a positive return on the first year of tuition at a four-year college. Indeed, if you drop out after freshman year, your ROI will almost certainly be negative. You have to stay the course to enjoy the benefits. The same is true of investments in health equity.

3. A standard ROI analysis typically ignores the indirect benefits that can accrue to healthcare organizations from investing in health equity. Such benefits include, for example, enhanced brand appeal and improved employee engagement and productivity> Neither does a standard analysis consider the strategic benefits that can flow from investing in health equity as America’s demographic, social and healthcare landscape evolves.

Because of these limitations, a standard ROI analysis can be more of an obstacle than an aid to sound business practice. It is one of the main reasons that healthcare organizations fail to undertake many worthwhile initiatives that would improve not only health equity but also their own financial health. Because it prioritizes near-term over long-term returns, it is also one of the main reasons that many of the pilot projects that do get launched fail to achieve scale, have limited impact and may be abandoned.