The Digital Front Door: Why Total Cost of Care Risk Is Not Inevitable

Advancements in technology could make a dramatic impact on the shift from volume to value.

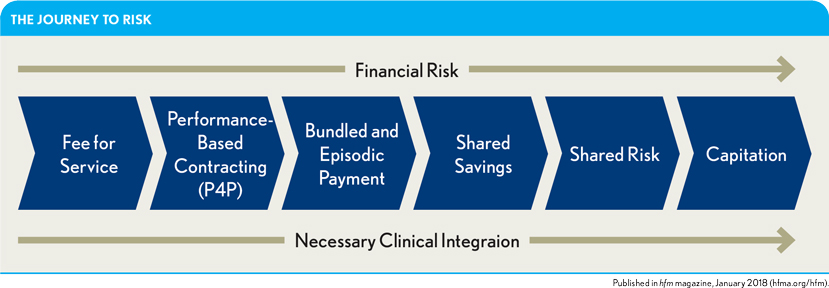

Both government payers and commercial health plans are conducting small experiments with providers involving bundled payments, payments for care coordination, and shared-risk contracts to find models that deliver better value for patients, defined as improved clinical quality and patient experience achieved at a lower cost. At the heart of these efforts, which constitute a shift in healthcare delivery, is the gradual transition to payment models that reward outcomes and place providers at increased financial risk.

Capitated payment models, where the provider takes a per-member-per-month payment rate for attributed patients, were prevalent nationwide decades ago. And these models remain the norm in places like California, where physicians have organized and taken risk for large patient populations because of the state’s prohibition on hospital employment of physicians. a Providers elsewhere, however, moved away from capitation because of the actuarial risks and corresponding financial losses. Understanding the actuarial risks related to the incidence and prevalence of disease has historically fallen within the expertise of insurance companies.

Many believe that providers have learned the lessons of early managed care and now have better analytics and resources to take on insurance risk. Proponents of the idea that providers should assume more financial risk say that provider consolidation and inceased vertical integration within integrated delivery systems have positioned providers to be more successful in this effort. Further, not paying providers for every unit of service will lead to the development of innovative care delivery models that reward lower-cost care and will bring the industry out of the paradigm of the 15-minute office visit.

But this steady march to capitation might not be inevitable—and if it doesn’t come to pass, it will likely be for reasons other than a failure to learn the managed care lessons of 25 years ago. Rather, it will be due to significant technological and cultural changes over the past 25 years that have changed the healthcare landscape, creating new challenges for providers.

The Rise of the Informed Patient

Today, patients can receive tremendous amounts of information related to their health conditions on their computers and smartphones. Big Data and machine learning are being used to render diagnoses more accurately than is possible through human reasoning, and to read medical images with clarity beyond what be perceived by the human eye. These improvements are not only making information cheaper and more accurate, but also changing the culture related to how information is delivered and consumed, particularly among the latest generation of millennials. b

These developments raise an important question: In an age when the promise of artificial intelligence (AI) could soon be realized, and when a smartphone app can potentially diagnose disease and then prescribe a treatment plan, does a primary care physician even need to be assigned to a patient? Few would argue that physicians should be at the center of designing these care tools and should provide oversight to any patient care protocols, but this process will require new ideas about how physicians perform their work.

Much of our thinking about payment in health care still relies on the idea of an “office visit,” even if that visit is over the phone or by video conference. Many seniors prefer talking to a live person, but millennials would rather that providers reach them using other means, such as text messaging. c Futurists already predict that the smartphone will be replaced by the next generation of Internet-enabled devices. Soon, what we have been reading on small screens may be whispered to us in our ears.

If the member’s health plan has the same access to innovative tools as do providers, and the health plan is the predominant financier of healthcare services, the provider—not the insurer— could become the middle man in the member’s care. These advances in technology and the coming generation’s expectations of information delivery might pit insurance companies and providers against each other to provide this digital front door to the patient. Arguably, insurance companies will not be eager to pay a capitated PMPM rate to primary care providers for attributed patients when these patients are receiving their care via an app or a telemedicine visit that the insurance carrier is providing.

A Technological Head Start for Health Plans

Insurance carriers already have much more experience than providers in constructing user-friendly patient portals for financial transactions (such as checking on claims or paying bills) and for patient information (such as estimating prices or finding a provider). It would not be a stretch for them to augment these portals with more tools to provide telemedicine visits (Optum’s NowClinic® currently serves patients in 48 states) or to provide complimentary apps that give patients easier access to care, and providers easier access to patients. Indeed, it is in health plans’ financial best interests to move in this direction because they are on the hook for financing the majority of their members’ medical spend. If an insurance carrier can provide medical information to its members using AI algorithms via a complimentary app and offer the same educational benefits as an outpatient office visit, the ROI is staggering.

Imagine the following scenario: A diabetic patient receives a text on her smartphone saying, “Your blood sugar is too high. You need some insulin, and it is being provided now.” That text did not come from her primary care physician. It was an automatically generated text based on a computer algorithm, triggered by her embedded glucose monitor. The insulin was provided to her by her embedded insulin pump. The patient didn’t require a visit with a physician for any of that to happen. This sort of situation, driven by AI and embedded health devices, is coming. Scientists are working on ways of distributing pharmaceuticals now that do not require patients to remember to take their pills. Currently, if a patient has questions about medications, the patient calls his or her physician. Imagine a world where such questions undergo AI processing and the best answers that medicine has come up with are presented in a way designed to be fully understandable to the average patient.

Providers, however, are upside down in this value equation. Unless a provider is at risk for the patient and receives a capitated rate for caring for that patient, the provider has a financial incentive to furnish that human office visit, not to deliver potentially the same educational material via an app that obviates the need for the office visit.

Insurance carriers surely realize that their best interest is not to pay the patient’s primary care physician for an unnecessary visit or to give the physician a rich monthly capitated rate for caring for that patient. Instead, their best interest is to invest in the technology that eliminates the physician from the equation. The health plans not only save a lot of money, but also become the trusted adviser to the patients. Their members then look to them for these services.

If health plans decide to move in this direction, they’ll likely vie with providers for the control of access to the patient. If the providers lose control, they will be in danger of remaining for the foreseeable future in a fee-for-service world where payers have more leverage and rates are even more tightly managed.

The amount of time before automation can truly disrupt healthcare delivery is unknown. Health care might be one of the last industries to be significantly affected by the digital revolution because of its tremendous complexity, safety concerns, and inherent personal nature. But automation is coming, and the savings it can promote certainly are needed as medical inflation continues to outpace the growth of the overall economy. That said, it might not benefit providers economically as much as it does consumers and health plans. Providers should ensure that they remain relevant in guiding this innovation and not just adhering to the way things have always been done, based on how they have always been paid.

Provider Tactics

The following are some tactics that providers should consider for positioning themselves to control the digital front door.

Continuously seek to improve patient access into the health system. Particularly for primary care, healthcare provider organizations should make sure that patients always are able to see a provider when and where they want to see one. Providing such an assurance might entail a more creative use of advanced practice and other providers. If patients are unable to get timely appointments when they want to see their physicians, they are more likely to begin looking elsewhere for their health care, turning to other providers or even to their insurance carriers, which might offer a more convenient care experience—perhaps a digital one.

Provide access to the provider’s digital front door. Even if doing so means disrupting the traditional delivery model of face-to-face patient care, provider organizations should invest in the tools and information systems to offer patients the care they need in a way that the patients find most convenient. It is not likely that payment models and delivery models will synch up perfectly to keep providers financially whole. Pursuing this tactic might mean a lower payment for some services, but providers need to adapt either by taking costs out of care delivery at a commensurate rate with the drop in revenue or by adding incremental volume through more patients. The market might become more competitive, but true market disruption rarely results in higher margins for existing business. The normal path of the product life cycle leads to increased commoditization of existing services and lower margins. d

As an example, pocket calculators often found in a business office can be purchased for just a few dollars and are essentially a low-margin commodity. In the early 1970s, a calculator with much less computing power cost over $200. The cost of technology inevitably comes down over time, and it is logical to assume the same will happen in health care, particularly if the insurer that is reaping the rewards is controlling the technology.

Partner with health plans to offer digital services and determine how to equitably split the revenue. Early adopters might have the advantage here in working with health plans to jointly create the ideal digital front door. If one subscribes to the idea that the amount of revenue in the healthcare system is as high as it is going to be, and that payment per unit of service will remain flat or even decrease, the best time to negotiate new agreements is now, before this disruption truly happens.

Vertically integrate. The model of team-based care is arguably better for both providers and patients because providers working in teams within a vertically integrated health system are better able to practice at the top of their licenses. Vertical integration should allow providers to effectively manage larger patient panels, thus increasing efficiency and lowering per-unit costs. Providers that currently practice in separate organizations have competing incentives in the current fee-for-service reimbursement structure. Aligning these incentives in newer, value-based payment models is difficult without one “economy” governing reimbursement that flows into the system of care. Health systems can manage financial risk and survive disruption much more effectively if they can be as economically agnostic as possible to how care is delivered to a patient so long as it meets his or her needs.

Change the physician compensation model to better align incentives for value-based payment. Paying physicians per relative-value unit is a significant barrier to changing behavior. This barrier is the crux of the conundrum providers face now and will face even more in an increasingly digital world.

As bigger, better, faster technology is developed, both providers and health plans should ready themselves to leverage that technology for greater value. Organizations that are prepared for a dramatic shift in both culture and payment structure will be best equipped to succeed.

Footnotes

a. Kongstvedt, P.R., Essentials of Managed Health Care, 6th Ed., Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2012.

b. OpenMarket National Survey, 2016. \

c. Koren, D., “What Millennials Want When It Comes to Healthcare,” MediaPost, Dec. 23, 2016.

d. Christensen, C., The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, Harvard Business Review Press, 1997.