Building a Magnet Physician Enterprise: A Critical Health System Priority in the Value Market

When employing physician practices to support their efforts to deliver value-focused care, health systems should understand that building an effective physician enterprise depends, first and foremost, on their ability to ensure those physicians are highly satisfied and engaged.

Over the past several years, the Triple Aim vision set forth by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, which underpins the Affordable Care Act, has gradually taken on a fourth component, so it might more aptly be called the “Quadruple Aim” of improving population health, enhancing patient experience, reducing costs, and improving provider work-life experience. a With this expanded purpose, leadership has a new priority to focus not only on the normal external threats to organizational health—such as the impact of mergers and acquisitions, increasing price competition, and new forms of contracting and risk management—but also on the internal challenge of building an active, fully engaged employed medical group dedicated to helping the organization improve quality and patient experience, while creating more efficient care delivery models demanded by the new value market. We refer to such a group as a magnet physician enterprise because of the inherent likelihood that physicians would find such an approach highly attractive.

Recent trends make it clear why such an approach is necessary for organizational health: The gradual decline of the voluntary medical staff and independent practicing physicians has fueled a corresponding growth of hospital-employed physicians, hospital-owned medical groups, and foundations. More than 40 percent of practicing physicians—some 150,000—were employed by hospitals as of 2016. b Meanwhile, an additional 50,000 are employed directly by or affiliated with insurers, as exemplified by UnitedHealth Group’s physician arm Optum, which recently acquired the 17,000 physician DaVita Medical Group; the proposed merged Aetna/CVS healthcare provider organization; and startup primary care innovators such as Village MD, GOHealth, and One Medical.

On top of the trend toward physician acquisition, the most recent primary care physician supply and demand forecast by the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) points to a shortfall of 42,000 primary care physicians over the next decade and a shortage of at least 33,000 in other specialties. c The shortage of physicians coupled with chronic nursing shortages may make it difficult to maintain adequate staffing, challenging clinicians to fill the gaps with improved productivity and better use of advanced practice clinicians as part of the primary care delivery system.

Given these trends, whether or not it is part of their overall strategy, all health systems of any size are now in the physician business: Whether a health system’s medical staff is organized as an employed medical group or as a separate foundation according to state law, the effectiveness of the physician organization will be the key determinant of the health system’s ability to compete successfully in the value market. With the voluntary medical staff gradually withering away, the most successful clinical organizations will be those that effectively create magnet physician enterprises that can attract and provide career opportunities for the best physicians, can develop a strong moral and ethical physician culture, and have strong physician leadership at all levels of the healthcare organization.

A Response to the Challenge of Physician Burnout

There is a strong business case to be made to make the investment in the internal improvements needed to create the positive work environment to bind physicians to their organization and achieve optimal physician engagement. A recent study by the Mayo Clinic finds the burnout rate among distressed physicians can be as high as 50 percent in some organizations, resulting not only in lost revenue due to reduced productivity but also in reduced quality of care, patient safety, and patient satisfaction. d

The Mayo Clinic’s CEO John Noseworthy, MD, and the CEOs of several other large health systems comment to their peers on the impact of physician burnout in a 2017 post to the Health AffairsBlog, noting that the cost of replacing a physician who burns out and retires early or switches to another group or career opportunity can amount to as much as $1 million, given the combination of recruitment costs and lost revenue. e

The personal and professional satisfaction of employed physicians will be a key issue for C-suite leaders, given the intensifying competition for recruiting primary care physicians and the strong indications that physician burnout is a national workforce challenge. Building a magnet physician enterprise will be a core strategy for health systems in driving revenues, controlling costs, and responding to the new challenges of risk sharing and value-based contracting. It will require the development of integrated practice organizations where health system leaders are willing to share the reins of power with physician leaders who will encourage their colleagues to take responsibility for the larger organization’s business success.

Factors Influencing Physician Professional Satisfaction and Medical Group Success

A recent national survey by the RAND Corporation for the American Medical Association sought to identify those factors that determine professional satisfaction that should be prioritized by hospitals and larger delivery systems for targeting within various types of practices, especially as they purchase or become affiliated with smaller and independent practices. f The survey findings on physician attitudes are instructional for health system leaders seeking to build high-functioning physician enterprises as part of their business strategy. RAND researchers gathered data from 30 physician practices in six states using a combination of surveys and semi-structured interviews. Among the key determinants of satisfaction that the report covers are physicians’ perceptions of quality of care, use of electronic health records (EHRs), and work quantity and pace—all issues of concern for any high-performing physician enterprise. The survey’s major findings focus on the following four major areas impacting professional satisfaction.

The importance of delivering high-quality care. Researchers found that a key determinant of professional satisfaction was the physicians’ own perception that they and their practices were facilitating the provision of high-quality care. The better their perception that they were providing high-quality care, the greater their professional satisfaction. Obstacles to their ability to provide high-quality care could be encountered within the practice, such as lack of leadership support for quality initiatives, or externally, such as the refusal by health insurers to cover what the physicians perceive to be necessary medical services.

EHR challenges. Physicians surveyed said they approve of EHRs, in concept, and appreciate the ability to access patient information and make improvements in quality of care. However, the new technology also has undermined practice satisfaction in many ways. Most notably, many physicians report spending as much time documenting patient encounters in the EHR as they do actually providing the face-to-face patient care. One physician executive commented, “Since our most expensive resources are physicians, this is perhaps not the best use of their time.”

Income stability and fairness. Surprisingly, few physicians in the AMA survey expressed dissatisfaction with their current levels of income. But income stability was identified as an important driver of professional satisfaction. Professional satisfaction was enhanced by payment arrangements that were perceived as fair, transparent, and aligned with good patient care.

The cumulative burden of regulations. The most commonly cited way to improve professional satisfaction and reduce burnout was to reduce the cumulative burden of outside regulations.

The AMA study recognized that physicians’ professional satisfaction also could be affected by broader health system changes—such as the emergence of patient-centered medical homes, accountable care organizations, and other new models of care delivery and payment for care. However, RAND found only scant evidence linking these newer organizational developments to professional satisfaction and physician burnout.

Other studies, including the previously cited study by the Mayo Clinic, indicate several predominating factors are contributing to both physician engagement and burnout, including workload, efficiency, work and personal life integration, work-life flexibility and control, culture and values, and the meaning of work. By prioritizing efforts and ensuring follow through at the most senior organizational levels, health systems that are aspiring to create magnet physician enterprises often can significantly reduce the number of drivers impacting engagement and turnover. Relatively easy fixes, for example, include reducing clerical burdens with the addition of scribes, balancing workload, and addressing problems with value and culture. g

Many large group practices and health systems operate under the assumptions that professional burnout and turnover among caregivers are primarily the responsibility of the individual professionals rather than a responsibility shared by the individual and management—and a strategic organizational priority.

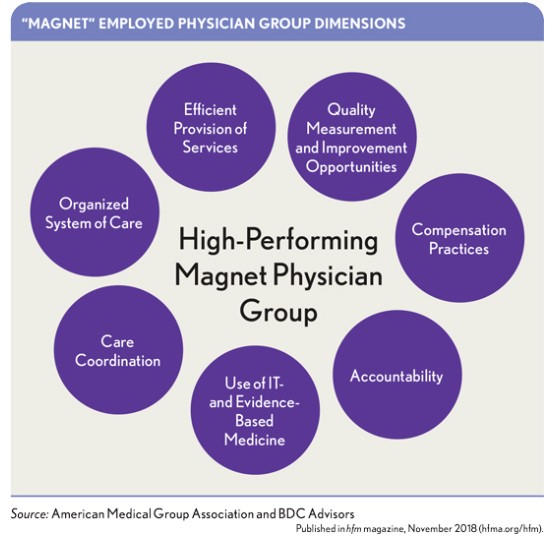

Elements of High-Performing Magnet Medical Groups

Based on our observations of successful health system medical groups, seven factors are critical to building an effective employed medical group. h

A governance model and culture of inclusion that involves physicians in operational decision making for the group and the overall health system. It all starts with moving the governance of employed physicians over time from a “docking station” model with individual employed physicians under individual employment contracts to an “integrated group practice”—a magnet that can attract and retain physicians in an increasingly competitive employment market. To successfully accomplish this change, it is necessary to create a formal, physician-led culture, with clear values that will govern medical group activities, and a centralized physician-led governance structure that places meaningful decision making in the hands of physician leadership via a dyad management model, as discussed below.

The perception of the group as a cost center in an integrated delivery system (IDS) rather than as an independent profit center. Hospital financial subsidies of employed primary care groups has been an issue for decades because it can be demoralizing to a medical group to be seen as losing money while the overall system is solidly profitable. To maintain clinicians’ morale and professional satisfaction, it is important for physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice clinicians to understand how the group contributes to the bottom line as part of an IDS, and for clinical staff to fully grasp the business success factors driving medical group performance.

A team-based approach that supports communication among patients, physicians, and advanced practice clinicians with a single plan of care across the treatment continuum. Such an approach includes shared decision making and collaboration between patients and providers concerning the risk or seriousness of the disease or condition to be treated and the cost or benefits of treatment alternatives.

The support of community at work. Physicians can benefit tremendously from having the support of a community of peers, both in dealing with unique professional challenges such as medical errors and malpractice claims and in celebrating personal and professional accomplishments. Paying attention to the “joy factor” in the workplace should be a priority.

The use of a dyad management model that pairs administrative and clinical leaders in a unified management structure. This leadership model includes the pairing of physicians, as clinical leaders in various specialty areas, with an administrative coleader responsible for finances, staffing, and options. The dyad management structure has proved to be a successful organizational tool for creating a common culture and a team-driven approach to organization improvement.

A compensation model that incorporates the Triple Aim markers of improving population health, enhancing patient experience, and reducing costs, while still recognizing the importance of productivity-based performance compensation. A magnet group uses compensation structures that provide appropriate incentives—including both productivity-based incentives and markers such as patient satisfaction and quality metrics—for both physicians and advanced practice clinicians. A recent survey by the American Medical Group Association (AMGA) recommends engaging well-respected physicians in standard care protocols that will have an impact on patient care and physician compensation. Organizations that rely too much on productivity-based compensation might be tempted to try to increase productivity by reducing physicians’ time with patients or by encouraging physicians to order additional tests, both of which approaches can have a negative impact on patient care. Working longer hours simply increases provider burnout risk.

A multi-dimensional human resource policy that supports physician and clinician well-being, accommodates work-life needs, addresses physician burnout issues, and creates a positive work and career environment. To be successful, a health system must align its altruistic mission to achieve the goals of the Triple or Quadruple Aim with the personal goals of its providers. The strength of an organization’s culture is a critical factor in determining whether it will achieve its mission. Keeping the values and mission fresh is an essential element of an effective human resources program.

Professional satisfaction for physicians is a byproduct of their ability to deliver high-quality care efficiently. A successful clinically integrated enterprise invariably has the interdisciplinary team structure necessary for effective network management. To successfully accomplish the transition to risk-sharing and value-based contracting, health systems require the data analytics and modeling necessary to stratify risk among patients with chronic health conditions for appropriate disease management, effectively manage care for the sick, and provide wellness and prevention services for the healthy.

Toward Value- and Risk-Based Contracts: Overcoming Obstacles and Ensuring Care Effectiveness

Despite the uncertainties in the market caused by efforts to dismember Obamacare, the trends toward value- and risk-based contracting are likely to continue. Implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, increasing employer and payer demands, CMS support for two-sided risk, and a push for market leadership will continue to support the transition to a value-based market. i The narrowing of physician networks also has compounded the need for effective primary care.

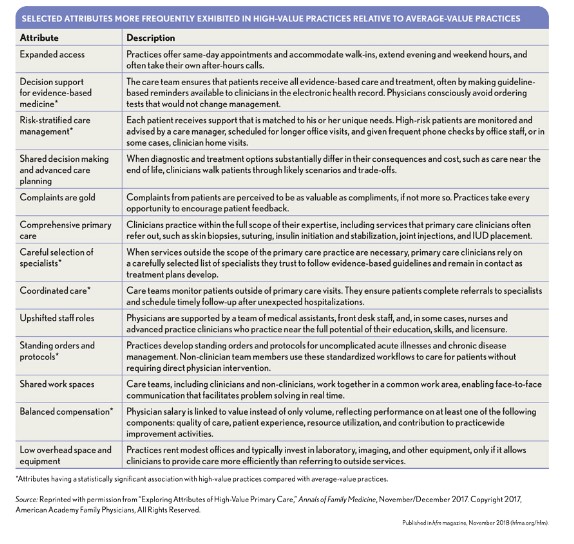

A 2016 AMGA survey of 450 multispecialty medical group practices reported that several large multispecialty practices—including UnityPoint Health in Iowa, Healthcare Partners in Los Angeles, and WellMed in Texas and Florida—had achieved positive value results by segmenting high-risk patients with chronic conditions and assigning case managers to those with multiple conditions. j The organizations reduced readmissions of medium-risk patients by focusing on transitions of care after hospitalizations, and they kept low-risk patients healthy by using routine care protocols during office visits to reduce gaps in care and prevention.

Although the AMGA survey data on payment trends indicate fee-for-service payment will continue to decline and risk readiness is improving, some significant impediments to risk-sharing and value-based contracting remain:

- Externally, in government and commercial settings, the greatest obstacles are the lack of access to administrative claims or immediately actionable health plan data, and the burden of reporting data to duplicative quality measurement programs.

- Internally, organizations lack capital resources to build the financial and analytical infrastructure necessary to manage risk or maintain the reserves that they require to take on increasing levels of risk.

- For the third year in a row, approximately 60 percent of AMGA survey respondents also reported that they had minimal or no access to commercial risk products in their local markets. k

Not all the issues and impediments discussed are shared equally among all organizations. But given current market trends, health systems will need to accelerate their integration efforts to realize the value of their medical group investments.

Despite the impediments, the authors of the December 2017 AMGA risk survey conclude their research provides “a clear rationale for (members) pursuing increasingly high levels of risk-based payments.” Their report notes that the fee-for-service model does not pay providers for the ever-increasing disruption from virtual telehealth visits, nor does it provide much support for the expanding move toward population health. Moreover, the financial incentives in risk contracts align most effectively with population health delivery models focusing on team-based, coordinated care.

Provider health systems with high-performing magnet physician enterprises will have a competitive advantage in making the transition from fee-for-service to value-based, risk-sharing contracts. Health systems seeking to create such an enterprise will need to establish and foster a common culture with meaningful delegation of decision-making authority to the magnet group’s physician leadership. This prospect may require changes to the health system’s governance or management to ensure that medical group leadership is involved in system-level strategy and decision making and has open and effective channels of communications with administrative leadership.

Footnotes

a. Bodenheimer, T., and Sinsky, C., “From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider,” Annals of Family Medicine, November/December 2014.

b. Avalere Health, Updated Physician Practice Acquisition Study: National and Regional Changes in Physician Employment, 2012-2016 , Physicians Advocacy Institute, March 2018.

c. IHS Markit Ltd., The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030 , 2018 Update, AAMC, March 2018.

d. Shanafelt, T.D., and Noseworthy, J.H., “Executive Leadership and Physician Well-Being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, January 2017.

e. Noseworthy, J., Madara, J., Cosgrove, D., et al., “Physician Burnout Is a Public Health Crisis: A Message to Our Fellow Health Care CEOs” Health Affairs Blog, March 28, 2017.

f. Frieberg, M.W., Chen, P.G., Van Busum, K.R., et al., Factors Affecting Physician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care, Health Systems, and Health Policy , RAND Corporation, December 2014.

g. Shanafelt, T., Goh, J., and Sinsky, C., “The Business Case for Investing in Physician Well-Being,” JAMA Internal Medicine, December 2017.

h. Eggbeer, B., Ahrens, C., and Fairchild, D., “Improving Medical Group Performance as Markets Transition to Value,” hfm, November 2017.

i. Speed, C., and Graziano, A., Taking Risk 3.0: Medical Groups Are Moving to Risk … Is Anyone Else? ” White Paper, AMGA, December 2017.

j. AMGA, Best Practices in Value-Based Payment , 2016.

k. Among large group practices responding to the 2017 AMGA risk survey, 17 percent reported having no access to any risk product, while another 42 percent reported that less than 20 percent of health plans were offering risk products in their market. These findings are an improvement from the 2015 survey, in which 70 percent of groups said they had little or no access to commercial risk plans.