States look to Medicare-based reference pricing as the solution to price variation for employee hospital services

By adopting reference pricing based on Medicare payment rates, two states may be leading the way to a profound change in how states pay for their employees’ healthcare services.

Overwhelmed by increasing Medicaid and employee healthcare costs, Montana and North Carolina have become leaders among states in the pursuit of aggressive strategies to reduce the prices paid for hospital services for their employees. If they are successful, hospitals and health systems will need to make good on their “Medicare break-even” cost-reduction goal.

Reference pricing: an emerging state strategy

Like other purchasers, all states have sought to reduce healthcare costs and cost growth by addressing both unnecessary utilization and unwarranted price variation. However, these efforts to-date have not yielded desired results. Against this back-drop, reference pricing is emerging as an alternative cost-containment strategy, where the payment variance in commercial rates for the same inpatient or outpatient service provided to state employees is reduced by setting a target for payments to a percentage of Medicare (e.g., payments for inpatient services will not exceed 200% of Medicare rates for the same service).

Montana was the first state to pursue this approach, and an NPR report notes the state has enjoyed success with its Medicare reference pricing. That success has led to discussions about expanding the approach beyond the state’s 35,000 workers to cover city, county and public university employees, according to an article in Kaiser Health News. And not surprisingly, the state’s Blue Cross Blue Shield plan has also indicated that it wants a similar price arrangement.

Meanwhile, North Carolina is in the early implementation phase of a similar model. An article in The Wall Street Journal notes that, under the North Carolina proposal, the average commercial rate for state employees would drop from 213% to 182% of Medicare payment for similar hospital services. (The revised amountwas originally 177% but was increased to provide more funding for rural hospitals.) The plan would cover about 727,000 state employees — including teachers, university workers, and state police — saving the state an estimated $300 million annually, with an additional $66 million in savings accruing to workers in the form of reduced cost sharing.

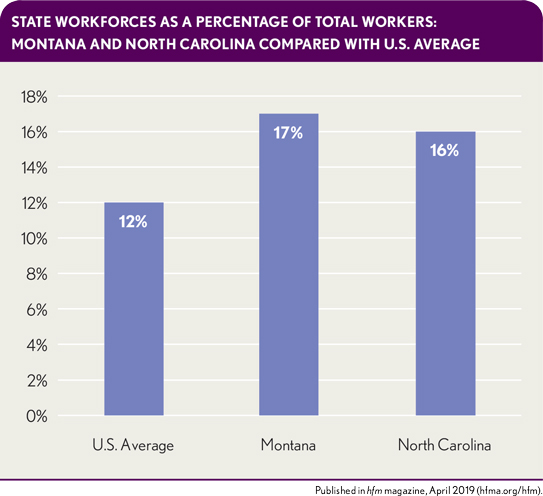

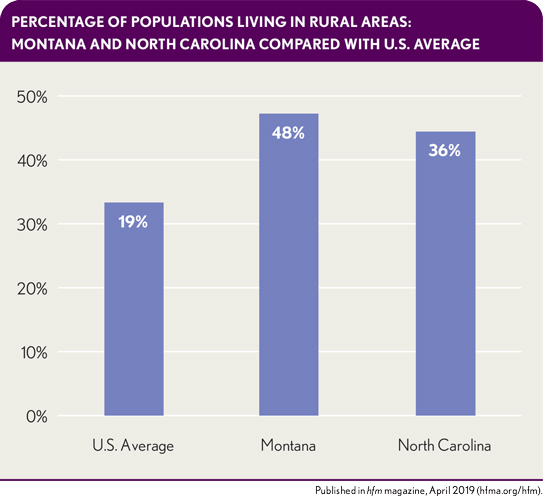

Some commentators, The Wall Street Journal article reports, have called into question North Carolina’s ability to force providers into Medicare reference pricing contracts, citing the state’s larger population and more complex provider markets. And not surprisingly, the plan is facing significant headwind in the state legislature, where the House has passed a bill blocking the plan, as reported by Modern Healthcare. It’s unclear whether a similar bill will gain traction in the senate, where the Senate leader is reportedly less inclined to intervene. North Carolina has more in common with Montana than might appear at first blush. Both states have larger-than-average state workforces and rural populations. Both have “must have” delivery systems. It is worth watching what happens in these states to see if this model could spread to other commercial purchasers and gain traction in other states.

State workforces as a percentage of total workers: Montana and North Carolina compared with U.S. average

Percentages of populations living in rural areas: Montana and North Carolina compared with U.S. average

Such a development would be of concern to hospitals. If all states were to implement Medicare reference pricing, most providers would experience a negative financial impact from rate compression. The only way providers can avoid such a result is by achieving a cost structure that allows them to achieve “breakeven” on Medicare rates. The emerging trend is a sign it’s time for hospitals and health systems to redouble their efforts to do so.

Mitigating the Margin Impact

If this reference pricing model expands, the impact on providers will be significant. A health system in Montana interviewed for this article saw a significant reduction in its operating margin as a result of the implementation of reference pricing. The health system’s robust portfolio of care redesign projects has enabled it to weather rate-compression-related payment policy changes (e.g. Medicare reference pricing, 340B payment cuts and site-neutral payment). Annually, the health system aims to obtain at least a 2% expense reduction compared with the prior year through continuous quality-improvement projects to help offset these changes and ensure the system is financially sustainable long-term.

Although many provider organizations have similar efforts, now is the time to reevaluate the effectiveness of existing efforts to ensure they are holistically yielding cost savings and not simply pushing cost from one area of the system to the other. HFMA’s Value-Project Report Strategies for Reconfiguring Cost Structure identified three key areas where members have reduced costs while improving patient outcomes and satisfaction: overhead, service delivery restructuring and clinical care transformation. Within each area, there are likely material opportunities to improve labor efficiency, reduce supply costs, rationalize spending on contracted services and reduce or reallocate capital spending.

Organizations that have succeeded in achieving savings goals have the following three characteristics in common.

Strong executive leadership coupled with a collaborative culture. Cost-restructuring efforts require a top-down bottom-up approach, which requires both an ability to drive change at the executive level while appreciating the finer details of performance-improvement efforts. Hospital and health system CFOs tend to be ideal candidates to act as executive sponsors or leaders of performance-improvement initiatives (see Green, R., Green, D. and Orsini, J., “The CFO’s Role in Accelerating Systemwide Performance Improvement,” hfm, June 2018). Yet these individuals will need a strong collaborative IQ and proven ability to credibly partner with clinical counterparts, because clinicians must lead the clinical transformation efforts.

Integrated analytics capabilities. The data necessary to drive cost-restructuring efforts has historically been housed on different database platforms. To develop a comprehensive view of the initial opportunities and monitor progress, health systems must integrate financial data (e.g., revenue cycle, general ledger, payroll and supply chain) with clinical data (e.g., electronic health record, evidence-based order sets and patient satisfaction). As prescribed in a February 2018 hfm article, these data sets will need to be standardized and validated to deliver one “source of truth” the organization accepts as accurate and complete.

Data-driven physician engagement strategies. Clinical transformation opportunities are the most challenging to achieve and sustain. However, when successful, they can yield positive year-over year-results while improving patient outcomes and experience of care. Organizations that have succeeded in this area are able to use their integrated analytic capabilities to identify high-performing physicians in key areas, according to and August 2017 hfm article. These physicians then are recruited to work with their peers to help them achieve similar levels of performance. Moving forward, organizations also should use their integrated data to provide point-of-care decision support to help physicians select the most cost-effective care pathway for patients. A July 2018 hfm article describes how the Texas Hospital Association has worked with 26 hospitals to provide a vendor-agnostic “data ribbon” within participants’ electronic health records to provide both cost and quality data to guide physician ordering.

Healthcare organizations require all the capabilities to successfully achieve and sustain cost transformation goals. Just one or two will not be enough. A June 2016 hfm article provides insight on what it looks like when these capabilities come together.

Organizations should not wait until Medicare reference pricing comes to theirs states. They should start now to develop the capabilities to succeed, and even thrive, in such an environment.